James Parkinson

Interview by David McLeavy

Published October 2017

-

James Parkinson’s work uses processes of material translation to reconfigure notions of object, space and body.

On a July morning I met with James over a coffee in Sheffield to discuss what he had been working on. The resulting interview is an account of that conversation.

-

So talk to me about these prints…

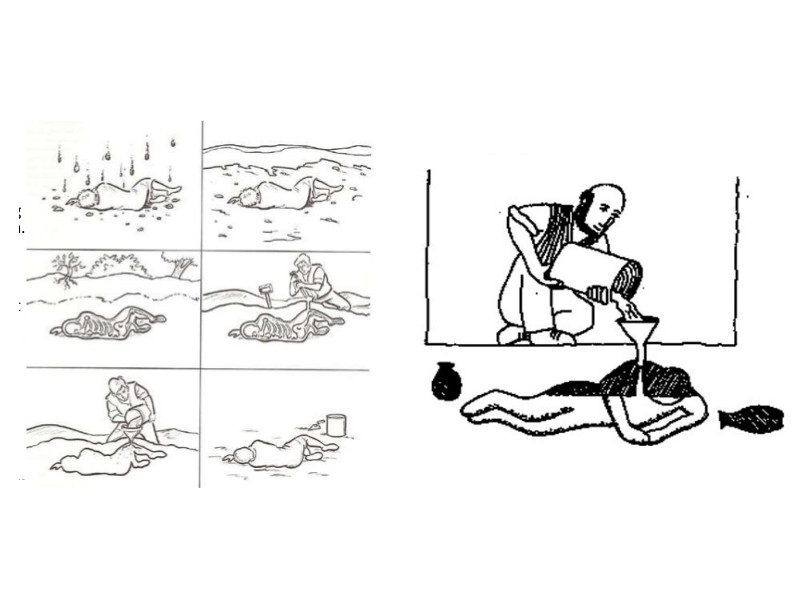

I’ve got some texts I am going to leave with you. In the past couple of years, my work has been informed by a constellation of research and fragments. I’ve been reading about the archaeologist, Giuseppe Fiorelli, who was the first person to cast the cavities in Pompeii that were left by bodies. As the flesh decomposed the skeletal remains were left in these cavities. He pioneered this technique where he would fill these spaces with liquid gesso, and then extract cured forms that resembled fragmentary bodies at the moment of death. So when they were presented they were really controversial as they were like replica and actual bodies, lodged together. I’m interested in that lodging, the relationship between the original and it’s possible reiterations and how they might intersect. At the time I was doing a residency at the National Museum of Wales where I began learning about the role of live field casting.

Diagram demonstrating Fiorelli’s casting technique

And I guess there is a great history of casting for museum purposes. I remember looking at the cast gallery within the classics department at the University of Cambridge, and how they were used for workshops but also how interesting this idea of bringing together multiple cultures and geographies under one roof. Almost aiming to replicate a time and space in some way, but inevitably creating a new space and site altogether

This idea of portability is really important. Especially thinking about how artefacts produced in this way can hold information that might otherwise be lost. The level of absence and embodiment that exists with this is also interesting. So it is the conditions of these artefacts that really interest me and this is what I have been working through with this series of sculptures.

Recently, I’ve been working with a friend who’s a tailor to create these large fabric enclosures from deconstructed clothing and fabrics. These are then filled with composites of acrylic polymer, plaster, concrete, and pigments. They are then suspended and positioned with intention, which determines the way they fluid composites begins to set.

The works you are referring to are the works you have shown at Cactus, Liverpool and Two Queens, Leicester?

Yes. Also when the fabric is removed there’s always this lodging that occurs, remnants and traces from one surface are held within the other.

This in some way sits outside of the traditional goal of casting as being a practice in which a direct and exact replica is the goal. Whereas what you are achieving is closer to the work of Fiorelli, in that the remnants and evidence of its formation and visible.

When I started making the work I didn’t know anything about casting. So the very first works at Cactus were about partially filling a volume, as simple as it sounds, and seeing what form would appear. It felt like a very immediate sculptural language, and one that seemed to suspend and transform familiar objects that I found around me.

The gallery in some sense offers a similar suspension, in time or location, with very little reference point to time or space when you enter the gallery. Your work seems to mirror that in some way. I wanted to ask you a little more about how this has developed from your background as a painter?

It’s hard to talk about that comprehensively, and there are still things I am addressing in regards to a painting practice but as I said earlier, everything seemed to be coming through my hand, which became frustrating. I also began doing research and forming ideas that would be better explored using a different way of working. There was also something very sculptural about the paintings, especially with the supports I was covering with films of paint. I am still interested in the conditions of painting or the grammar of it, but I felt I somehow painted my way out.

Of course you can be interested in painting but perhaps not interested in making a painting. I wanted to talk a little more about your show at Cactus. You included a text alongside the sculptural objects which had been written or transcribed from a conversation between yourself and a conservator about the processes of casting….

It was during the time I was doing a residency at a museum in Wales. I interviewed a number of the museums staff, including a conservator called Penny, about the process of excavating wall paintings. The museum itself is known as a living museum. Architectural buildings of note are moved to the museum for display, so the whole site fuses the original and the replica to create a believable whole. We began speaking and I recorded the conversation, without having the goal of transcribing it in the future. Penny spoke about the process of excavation and the gradual removal of layers of matter to find an image. The language she used really fascinated me. The conversation stayed with me and I began thinking about transcribing the recording and what might happen in this process. What might get lost? And what be gained? I wanted to be honest in the transcription process, and not tidy anything up too much, so the resulting text has a clunkyness to it.

Penny Hill (conservator at St Fagans Museum) and a wall painting she excavated from St. Teilo’s Church

So it became more symptomatic of speech itself and the traits of spoken word as oppose to a more formalised piece of text?

Yes that was really important in relation to the sculptures. It felt like a return to physicality in both the sculptures and the text, through these interruptions and grammatical knots. I was interested in exploring the conditions of the artefacts in question and recording this in writing and also how that worked as process of translation. This was the first time I ever brought these two things into the same space.

One of the reasons I mentioned it is that I am interested in the balance between giving and holding back information from the public and how text can be the mediator for an audience to access the artwork or the context that it exists within. I wanted to ask you how you feel about writing that introduces your work or something that talks about your work in a more direct way.

I was really keen to have the writing in that show as it introduced someone else’s voices into the work, as that was what was happening during the residency itself. In the last few shows I’ve had very little accompanying text. I don’t have a position on that so to speak, but I have been trying to think about the most accurate way to disseminate interesting and relevant information and if a press release is the most useful way to let people in. I want to be generous but I also sometimes want to facilitate an unmediated experience with the work. There are also other types of exchange as oppose to writing.

A purely physical or visceral exchange doesn’t exist very often outside of the art world, so perhaps it is something worth cultivating?

I also don’t want to make things linear, as this isn’t how the work exists for me. As I mentioned earlier, it’s more of a constellation of things that are informing making processes, and I am interested in how these relationships can be made visible to other people.

Is that the same for the show at 2 Queens?

Yes very much so. And it had a very particular title.

Talk me through where the title Ablat came from.

‘Ablation’ is the procedure of removing bodily matter through burning, so it’s a medical term, and the origins of that come from the word ‘ablat’, to remove or take away. The sculptures were partial and fragmentary.

With the 2 Queens show especially, you included a blue draped material. Where does the colour choice and inclusion of the material fit it? Is it related to the tailoring aspect you mentioned earlier?

I wanted to create a stage or runway for the sculptures. The material also skinned the space in someway too. It was a leftover the gallery had so it felt appropriate to recycle or retrofit the space with it. The colour also helped to elevate the work in some ways.

Wrist brace

It seems that the objects that you have brought in today relate very closely or have been a product of the shows you have just been describing.

I have gone from having a studio to not having one and I am interested in opening that idea out and thinking about production and production spaces. I wanted to see what is available within the means that I have, so I have begun making these cyanotype prints. I’m really interested in how the process sits somewhere between photography and print-making and how the resulting images are residual.

I also recently connected with an orthotics lab just outside of Leeds who make prosthetics and devices for sports injury. I’m familiar with some of these devices from playing sport but the production methods used are really fascinating and strange. I have been doing a lot of research recently into post-war hybrid sculpture, when the human form was being re-imagined and connected to mechanical, animal or plant forms. In the orthotics lab they have these plaster casts that they use to form heated plastic. The heated plastic looks like icing as it is stretched around the contours of the cast. A vacuum-forming gun is then used to extract air and create a more accurate fit.

This produces strange excess, which is removed and discarded. It’s like a compressed ribbon of plastic [presents off cut].

Thermo-formed plastic off-cuts

Where does the colouration come from?

They actually allow customisation; the user can customise the device with their own image. This is applied to the plastic in an oven as a heat transfer. I’m not entirely sure where these ideas are going at the moment and I don’t consider the objects as works. I’m also very aware that people with physical disabilities use the service so skimming it for an aesthetic feels intrusive and inappropriate.

I’m really interested in these Assyrian bas-reliefs [presents a photo] and this text by Gottfried Semper where he talks about material translation and the influence of fabrics in architectural history.

The reliefs are so beautiful and intricate. The depiction of fabric filled and positioned by flesh, the fixing of posture, it’s very seductive. I’ve always liked the description of Jacob Epstein’s Rock Drill as being a moment of ‘muscular truce’. I can’t remember who wrote or said that but mentioning it feels appropriate.

Detail from an Assyrian bas relief depicting a lion hunt. 645 – 635 BC

It seems about potential in many ways. The potential for movement, the potential or suggestion of a body. Similar to seeing clothes that are not being worn, you get the suggestion of it’s function without seeing it being exercised precisely. I think it leads nicely to your use of fabric, specifically discarded materials from items of clothing.

Presence and absence are important factors in the work, there’s always a trace of a previous inhabitant or user. So bringing these fragments together is a reconfiguration and approximatation.

-

James Parkinson lives and works between Bradford and Mexico City. Recent exhibitions include Nomadic Vitrine at Recent Activity, Birmingham, Ablat, 2 Queens, Leicester, Thick Support, STCFTHOTS, Leeds, Slower Volumes, Cactus, Liverpool and The Spirit Of The Staircase, The Sunday Painter, London.

http://jamesparkinson.co.uk/

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Lizz Brady

-

© 2013 - 2018 YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED