Scott Caruth

Interview by Melanie Letore

Published June 2015

-

Scott Caruth's practice includes photography, book making and writing, most of which focuses heavily on political and social issues. Whilst having a strong relationship with photo journalism, Caruth's work embodies more than just documentation and provides a critical look at prominent local and global issues.

-

In your photo-books 'Canned Controversy', 'Alan Sugar Must Die' and 'Debut', a few of your photographs may point to a political engagement on your part. With ‘Molatham’ and ‘Charm Offensive’ and the subject of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, you delve deep into the loaded subjects of history, politics and human rights. Do you feel like these recent projects are a natural evolution or a departure from your pre-2013 body of work and why?

I made ‘Canned Controversy’, ‘Alan Sugar Must Die’ and ‘Debut’ in my final year at art school as a means of learning the process of book making, as I saw potential in self-publishing to be a practical platform for presenting and disseminating work independently after graduating. Throughout my time in the Fine Art Photography course I rarely had photographic outcomes for any project I undertook despite taking photographs all of the time. I sort of viewed them as being ‘on the side’ of everything else I was trying on for size, like performance and video etc. At that stage I was becoming increasingly politicized and participating in more and more political activity, however I found myself in a deadlock where I couldn’t quite address or explore any of the issues that I was engaged in without being overtly literal.

Those books are made up of those photographs that I was making ‘on the side’ throughout the course and in reviewing and selecting them at the end of that experience, I began to relate to that process itself a lot more than any of the grand political gestures I had attempted (and failed) to make. I started to cultivate a different relationship with something that, despite being omnipresent, I had failed to pay due attention to.

So on the one hand, thematically and sometimes aesthetically those works are of course part of a natural progression to the trajectory of my more recent work, but on the other hand there are lots of elements that I have made a deliberate point in departing from. I associate them with a particular stage in my life that was very much a learning process and as a result of that it’s difficult for me to disentangle a sense of naivety when looking at them now. At that stage I was primarily concerned with their form and their narrative unto themselves as a collection that revolved around my own personal and immediate reality at the time. As a result of this, I feel that they fail to contribute to a wider conversation about the medium in any significant way and my understanding of and interest in that conversation largely stemmed from my experiences in Palestine after I left art school.

We Are Dreaming Of A Roman Italy, Video Still, Rome, 2015

Can you please tell me a little bit more about how 'Molatham' and 'Charm Offensive' were born? What were your intentions as a photographer – did you set off with a clear idea in mind of the body of work you were hoping to make, or did some aspect of the work arise once you were there? How did you manage that balance?

I sort of feel the need to split my answer to this question down the middle. On the one hand, I travelled to the West Bank with the full intention of participating in non-violent resistance to the Israeli occupation. I don’t think that it would be wise for anybody to do so without being clear about all of the consequent personal and political implications.

But when it came to anticipating how any sort of creative practice could play a role within that, I didn’t really have a presupposed idea of what kind of form it could take. At that stage, as I mentioned before, I was still sort of negotiating my relationship with the medium and that process becomes incredibly loaded in the context of Palestine. All of a sudden, I was confronted by the multitude of implications embodied within the camera as an object and photography as a medium. It was this process that instigated a questioning of my relationship with the medium up until that point, and ultimately led me to depart from the sort of photographic work I was producing that you mentioned in the previous question.

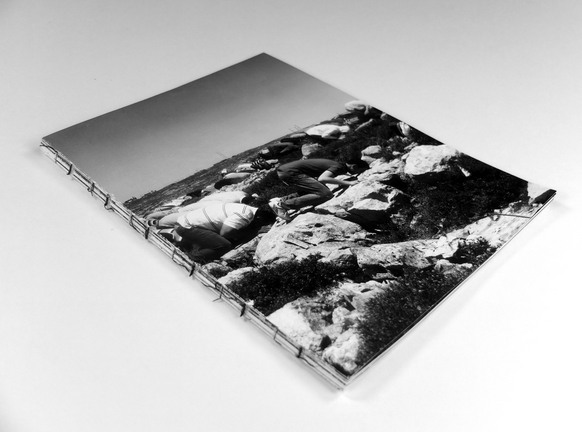

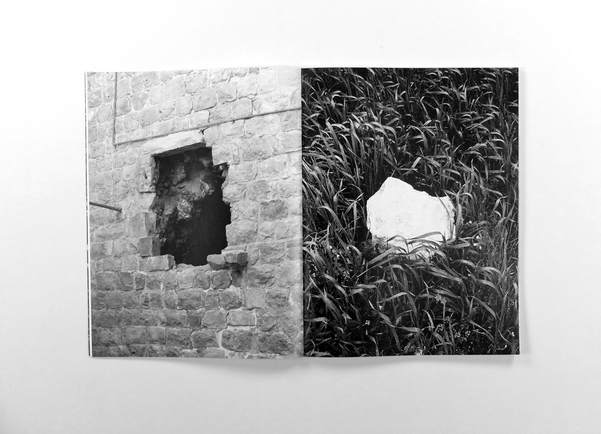

Charm Offensive, Publication, 2015

Charm Offensive, Publication, 2015

In your essay “Photography Is Not In Crisis, We Are”, you write that “advancements in camera technology have brought first hand documentation of events by those involved with them to the forefront over those sent to alien situations for the first time with a pre-supposed agenda informing their image making”. As a non-Palestinian, how did you navigate this issue yourself?

Part of being active with the International Solidarity Movement requires a constant awareness of your status as an outsider. As a principle, our actions were always Palestinian led and our presence was maintained at an invitational basis from the communities we worked within. It was this status of being non-Palestinian, being ‘internationals’ that had been invited to participate in acts of resistance that defined our tactics, and making ourselves visible formed the basis on which we could intervene in or deter acts of oppression. Photography played an instrumental part in my role as an activist, which in turn came to inform my role as an artist. For example, one has to discern between instances where taking a photograph can act as an extension of your solidarity work (documenting soldiers brutality, deterring settler violence etc.) or where it can compromise it entirely (photographing the faces of those participating in direct action). The struggle that we participated in revolved largely around questions of visibility, like why was it beneficial for my western face to be visible on demonstrations whilst all of the Palestinians around me were clad in balaclavas? And it was these questions that informed both of the projects that came out of that experience. So to answer the question, the process of navigating myself through these issues was rooted primarily in activist concerns, which is why I made the decision early on not to look back at any of the photographs I had taken until I returned to the UK. Although I had growing ideas of where the work might go, and had been documenting specific things, the process of production felt like it needed to be entirely disentangled from the context in which I had arrived first and foremost to be an activist.

So photography in this context is highly problematic; can you please expand on its relationship with the occupation?

Photography occupies (no pun intended) a unique space within the process of ethnic cleansing: between the physical erasure of bodies and the cultural erasure of their memories. It constitutes two integral mechanisms of a military occupation: surveillance and representation. Paradoxically, the cameras of the IDF constantly document the very entities it refuses to acknowledge or recognize as part of a process that ultimately seeks to erase them.

Israel’s process of ethnic cleansing and nation building is rooted in mythology and as such, it reveals the mythological nature of images in its quest to establish a narrative. Therefore photography’s capacity to provide evidence or to successfully document in this context is constantly coerced and challenged.

Do you see yourself as an artist or a photojournalist? Does the distinction have any validity with you?

Yes, I basically spent the entire time trying to articulate this distinction and attempting to locate myself within that equation.

Any visual medium performs a tension between form and content, but I think that this is particularly amplified within photography due to its unfortunate and false association with evidence or fact. This becomes even more problematic within the field of photojournalism as a commercial enterprise, wherein lies the reality of re-victimization, aesthetisation of suffering etc.

By participating in very physical, direct activism, by directly intervening, I was automatically excluded from acquiring the status of an objective observer. But the very existence of that status in itself is incredibly problematic, if not nonsensical. With all of our actions, we had to be sensitive to and reflect upon the ways in which our presence could shape the course of events. But in observing the behaviours of photojournalists in the same situations, it was clear to me that their ‘status’ rarely underwent such a critical reflection and this was particularly visible in observing the sort of moments that these photographers could be seen striving to document over and over again. This deadlock within photojournalism has generated a very narrow and shallow narrative of the Palestinian struggle. It has accustomed most audiences to a victim/terrorist polarity within the Palestinian subject and its penchant towards revolving around seductive, physical manifestations of violence lends to the idea that such eruptions occur against an otherwise blank or peaceful backdrop. By pursuing neutrality in a context where no such balance exists, photojournalists ultimately play into the hands of the oppressor and fail to communicate the ultimate irony of the occupation; that there is no balance, or two sides, merely the omnipresence of Israeli domination over every single aspect of Palestinian existence.

What you say about photojournalism and its shallow narratives is interesting; can you please expand a little on the role of representation within the photojournalistic context?

Although all of the issues I have discussed so far have been through the prism of the Israeli occupation of Palestine, out with the specificities of that context, they are issues that present themselves within the process of documenting and ultimately representing anything anywhere. Any investigation into or attempt to play a role within the establishment of a narrative or to represent needs to be approached with a critical perspective, a space for which is excluded by the demands placed on today’s professional photojournalists. If one wanted an example of how things would end up without such a perspective, then todays mainstream media-scape would be an excellent example. The dematerialization of the photograph’s object-hood in the digital age has coincided with its role in mass media’s de-contextualization of events and its alienation of broader historical and political narratives. However, its permeation of crisis, its sense of urgency is not merely some attempt at juggling the magnitude of information that new technology has presented to us. Connections need to be made between this media culture and the prevailing market-based neoliberal ideology, under which political structures govern by the permeation of crisis, generating a psychic and political condition in which it becomes increasingly difficult to reflect, contextualize or ultimately, to imagine an alternative.

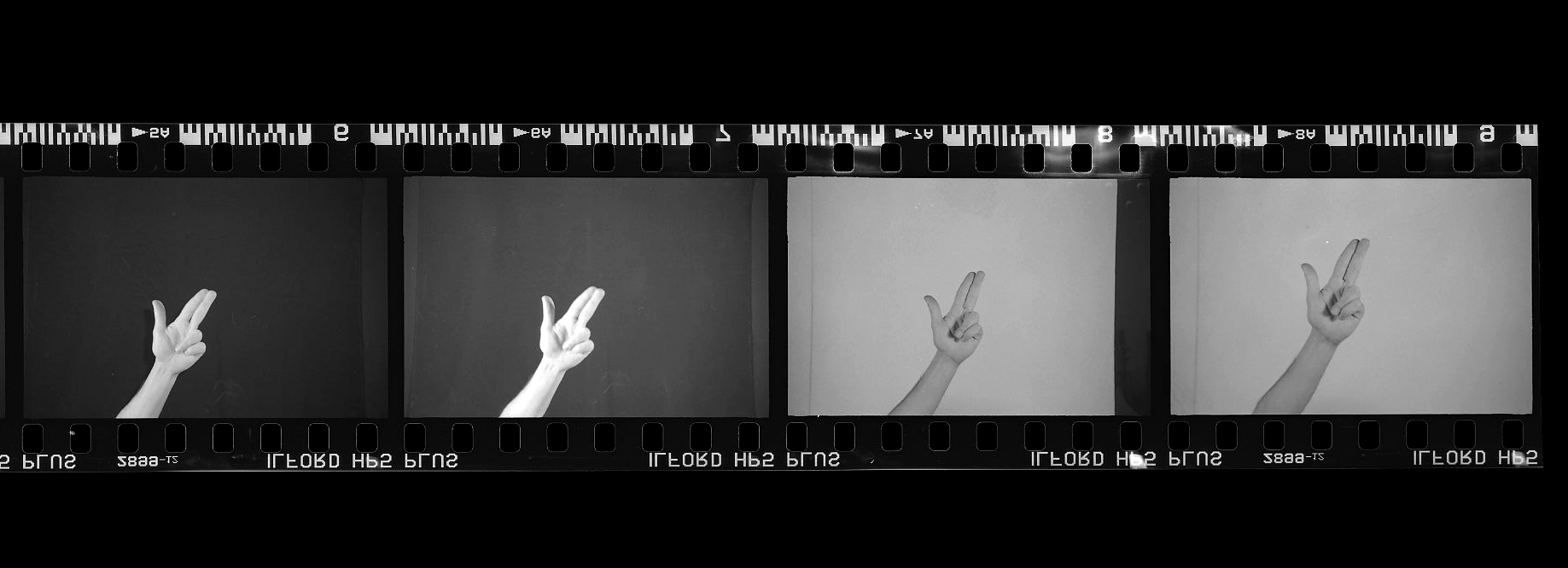

P.38, Modena, 2015

None of my questions have been about your excellent photographs per se – how does this sit with you?

I’m glad that the aesthetic considerations of my photographic output should play such a small role in a conversation about my practice. To say that those considerations are an afterthought wouldn’t quite be accurate as naturally they are important considerations that I do take seriously, however within the whole process, from writing to researching, the actual time spent on these considerations seems relatively insignificant.

My technical knowledge of the camera and its processes are pretty limited and I don’t have much interest in learning any more than is necessary for whatever it is that I’m working on at that particular moment. This stems from the reality that after all of the researching, organizing, interviewing, collaborating, travelling and planning, the actual making of the image itself is the only part of the process in which I have the potential to act intuitively and I sense that this might be compromised by knowing the exact technical steps to follow in order to produce a certain thing. Naturally however this methodology comes with its own set of risks, plenty of my ideas have failed to be realized because of something as silly as forgetting to press a certain button before shooting for 4 hours….

Talking about publishing, you touch upon this in the last paragraph of your essay “Photography Is Not In Crisis, We Are”. I am very interested in hearing you expand on the subject of self-published photo-books. What is it about the medium that encourages/drives you to use it?

A good example of the reasons behind my attraction to self-publishing can be told through the process of the ‘Molatham’ project, which was problematic in the context of the white space in which I exhibited it. My intention to show these studio portraits, these instances where Palestinians had represented themselves, absorbed a whole load of additional ethical implications within the context of a gallery.

Part of this stemmed from the fact that I had actively reproduced the portraits in their physical form as objects. There was also the exclusivity ingrained within the temporality of the exhibition itself, but the biggest tension that arose within the process of exhibiting that work presented itself within finding the correct balance between text and images.

Twofold, The Savoy Centre, Glasgow, 2015

Yes, can you please talk about the text/images relationship within that project?

Text is an integral part of the 'Molatham' project, in placing these images within a wider historical and political context without which one might view the project as being something quite sinisterly carnivalesque. The prominence of these two aspects could be delegated much more efficiently in the format of a book, where the text acted as a component to the whole as opposed to an accompanying detail on the wall where it risked dictating rather than contextualizing the viewers experience.

This is why I published the book to go along with the exhibition that was given to each visitor to the show for free and in doing so I realized both that the project had the potential to go much further but in order to do so it had to take the form of a book. That is not to say that the format of a book is not also potentially problematic, however I feel that my capacity to introduce the context and narrative necessary for the project to reflect my intentions is much more negotiable within that format.

Molatham, New Glasgow Society, Glasgow, 2014

Molatham, New Glasgow Society, Glasgow, 2014

Congratulations on being Stills Artist in Residence 2015! What are your plans for your time in Rome? Can I look forward to any other plans/projects/ideas/books/exhibitions? Who or what is inspiring you at the moment?

I used my time during the residency gathering as much material as possible that I’m currently in the process of developing into two separate projects.

Firstly, I spent my time at the Fondazione Fotografia in Modena looking at the relationship between the photographic archive and the Autonomia movement of the 70’s. The Fondazione has a pretty huge photographic archive that I spent a lot of time exploring and thinking about how that type of resource could possibly deal with a movement who actively refused representation or aestheticisation. Autonomia are of particular interest to me because unlike other European leftist projects of the time, they called for a complete refusal of work, not for better conditions within it, but for a complete renegotiation of the framework of existence itself. They also emerged from a historical moment in which there was a paradigm shift from material to immaterial labour and they attempted to respond to the new ways in which the mind and body were coerced under this new semio-capitalism. Part of this process naturally revealed the increasingly extensive role that the image played in these enhanced forms of exploitation, which is why I think that they are so important especially when used as a lens from which to consider documentary’s relationship with materiality. This project will take the form of another self-published book.

The second project I undertook is a video piece that explores Italian fascism’s appropriation of ancient Roman aesthetics, stemming from Mussolini’s slogan ‘We Are Dreaming Of A Roman Italy’. The piece revolves around two sites in Rome which were built during Mussolini’s reign; Stadio Dei Marmi, a sports ground that contains 60 faux Roman marble sculptures of the idealised man, and Cinicitta, the largest film set in Europe which contains a 70 acre set of ancient Rome on the outskirts of the city. The Italian philosophers who played key roles in the Autonomia movement, such as Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi and Antonio Negri, have largely informed both of these projects.

We Are Dreaming Of A Roman Italy, Video Still, Rome, 2015

Do you feel that there are similarities between these projects and the projects discussed above?

There are parallels between the ways in which the Italian State and the Israeli State utilised the image against those opposing them. The Italian State implemented a ‘strategy of tension’ in which it carried out covert terrorist attacks throughout Italy in the movement’s name, effectively reducing the struggles attempt to vocalise a narrative regarding systematic violence and exploitation to one that revolved around mediated acts of physical violence. The process of disputing allegations of violence was problematic for the Autonomia movement as historically they stemmed from the same organisation (Poterre Operaria) as the Brigatta Rossa, a left wing terrorist faction which engaged the state in its own mode of physical violence, something that Autonomia were vocally opposed to. The image is a fertile resource here for the state to lump all of its opponents into the same category of perpetrators of violence (as is constantly employed by Israeli PR) and such images of violence are exploited by the state in producing claims that they occurred against an otherwise peaceful backdrop for which the state is required to maintain. On top of all of this, the Carabinieri systematically destroyed the individual and collective archives of the movement’s activists, tarnishing their capacity to establish their own narrative, an issue that formed the basis of my work dealing with the Palestinian struggle.

-

Scott Caruth lives and works in Glasgow. Recent projects include Molatham : Studio Portraiture From The West Bank, The New Glasgow Society in Glasgow and Doomed Gallery in London, 2014, Canned Controversy and Alan Sugar Must Die. He has also self published the book Charm Offensive which includes a selection of his photography and two essays.

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Rebecca Molloy

-

© 2013 - 2018 YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED