Anika Ahuja

-

Interview by Caitlin Merrett King

-

Published in June 2025

-

I’m standing in the back garden of a classic Glasgow tenement building. A cobbled together water fountain trickling gently, framed drawings bound to the fence demarcating this garden from the next, and a large ethereal sheet pegged to the clothes line, gently wafting in the calm evening air. The sheet holds a printed image of the shadow of a man through a curtain relaxing, reading a book, taken by Anika Ahuja on her iPhone on a train whilst travelling through India. The work, entitled dreams of Erebus (2025), exhibited in So Close, organised by Ahuja in the common spaces of her apartment building, is subtle and calming. The way it flutters in the grey Glasgow breeze is beautiful, and when I see it a week later in Ahuja’s studio I notice the intense detail of the shadows she has captured in the grainy photo.

The image captures an immediacy and an intimacy that exists across Ahuja’s rigorous practice. Within her drawing practice, she painstakingly depicts images taken on her phone of reflections and windows, portals to places of worship, such as the drawings entitled, Leadlight (ecstasy), (2025) and Leadlight (agony), (2025) hung in the building’s stairwell in So Close of blacked-out Gothic, Decorated style windows. Both ‘dreams of Erebus’ and these drawings create intimate moments for the viewer using delicate, translucent materials: mylar and cotton, which are unframed and raw-edged, displaying their own making. But there is a lightness and a darkness within the work and these drawings present an impasse to the viewer; are you inside incapable of seeing out? Or outside incapable of seeing in?

To bring a group of friends together, as in So Close, attempts a different way of presenting and being outside of the institutional setting that is all about joy. As we speak in her studio, Ahuja mentions the search for and necessity of joy several times. For her, what is newly important within her practice, is finding what brings her this happiness and excitement. Ahuja’s practice also provides this. I keep thinking about the man reading on the train, his image rippling across the curtain – on the other side of the curtain on the train – and the replication of his reclining body offering the viewer also a moment of repose and pleasure – just slightly out of reach.

dreams of Erebus, inkjet on cotton, 2025

—

You just organised a group exhibition in the close and garden of your flat, amusingly titled, So Close, what was the incentive behind the show? There's a huge history of people doing exhibitions in their flats in Glasgow, but, for you, why do a show in your flat?

I am curious about spaces that exist as corridors, not in the literal sense, but spaces we pass through, often in large numbers. Transitional spaces, democratic spaces, shared spaces. I often reflect upon what can be seen as the exclusionary or intimidating nature of the traditional art space, so I think I am often trying to consider that in my practice, and in how I am interested in presenting work.

I suppose after moving through institutions over years when trying to develop a sustainable practice as an artist, you often encounter the heavy doors and bureaucracy of those spaces. I have experienced a level of fatigue with the nature of traditional institutions, so having an exhibition in the “inbetween space” that is quite literally shared by the collective tenants in the building felt compelling to me. Glasgow tenements have always housed a number of families, and have seen so many types of people and experiences move in and out of their doors. There is a level of collective respect, a social contract in these spaces amongst tenants that is different from the hierarchy of traditional institutional art spaces. Having a show in the shared close of my building required consent from my neighbours, as well as offered an invitation to the public to a shared private space. It was intimate in invitation and experience, everyone in close quarters, occupying narrow stairways and corridors. It was very special, and received with so much warmth and support from my neighbours, and I am so grateful to everyone that came out.

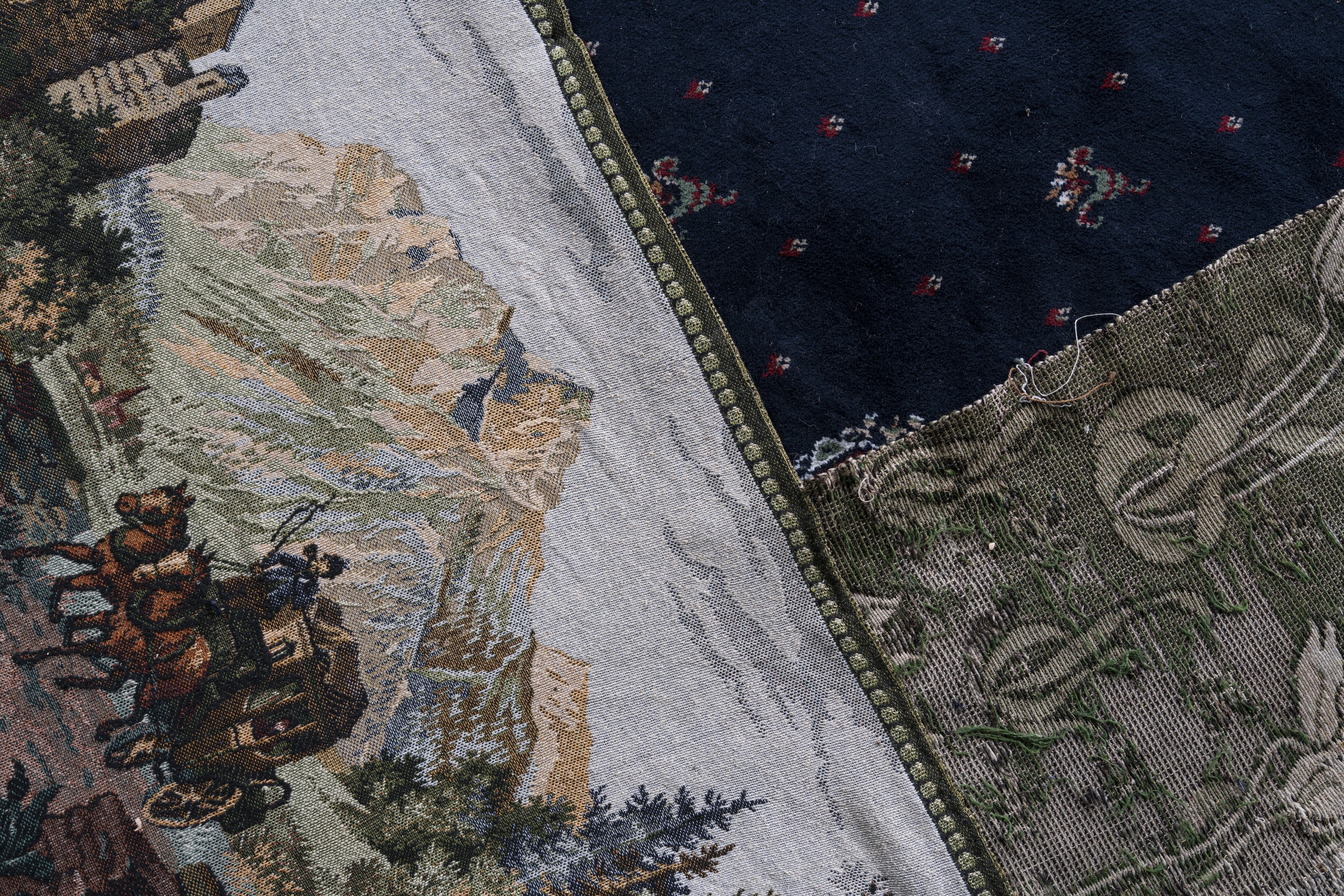

beyond the garden wall, [detail], recycled rugs and carpets, wildflower seeds, soil, 2021

How is liminality discussed within your wider practice?

I am drawn to the “inbetween”; seduced by window dressings, reflections, borders, memory, echoes of corridors, heavily trodden thresholds. These ‘spaces’ feel unknowable and there is something inherently urgent and romantic about something that feels impossible to hold, where time passes silently, and things often appear unclear.

We are always very pressed to identify and classify all things, quantify things, dissect them into binaries, to see things as black and white. I am interested in nuance, error, misunderstanding, multiplicity.

My interest in the “intangible” is maybe an attempt to create understanding or gain clarity, but I think I am actually more curious about the way in which things appear obfuscated, or are open to interpretation. I am less interested in a fixed way of seeing or knowing, but rather pushing the bounds of understanding. What is allowed in, and what isn’t? I am interested in questions that don’t necessarily have answers.

You did your undergraduate degree in drawing; how does drawing feature in your practice and what is your relationship with the medium now?

I hadn’t touched drawing in about a decade until last year. Like many people, drawing and mark making was my introduction to art as a child. It was play, experimentation, expression, meditation, joy. And until I began engaging with art in an academic sense it remained that way. Unfortunately in my time in art school I became very stifled by the parameters of working with concept and justification, and it made it difficult to draw in a way that was pleasurable, or engaging. In fact I often couldn’t get started unless I could justify the validity of drawing, so I fell out of love with it. Now I am much more interested in trying to reconnect with drawing as an attempt to play again. A pencil and paper is such a simple democratic medium, everyone can draw. So I am trying my best to approach drawing as more of a personal project, an attempt to play again. Which is sort of how I am trying to access all parts of my practice at the moment. I used to be so serious and concerned with justifying my work, now I just want to find a way to enjoy making again, to appreciate the simple intentional action of making a mark.

beyond the garden wall, [detail], recycled rugs and carpets, wildflower seeds, soil, 2021

Your work is really multidisciplinary, often moving into installation. I'm thinking about the work you made for the exhibition, Tittle Tattle at 5 Florence Street in Glasgow and then for the exhibition When Bodies Whisper at Timespan in Helmsdale. Could you talk about this work and the creation of spaces, particularly spaces that reference worship and religion within your practice?

I fell into installation, when I fell out of love with drawing. I love objects, I love materials, I love how they carry inherent value, but how they can mean different things to different people.

Misunderstanding, and dialogism are such important parts of my practice. I always use the example of a baseball bat here; placed behind the till in a corner shop, the baseball bat is a weapon, a means of self defence. In a little boy’s bedroom, a reference to a national pastime, masculinity, athleticism. The value of an object changes depending on where it is placed, or who you are, what you have experienced. It is just as important to me that some people don’t understand the work as much as others may, because that feels like an honest reflection of the world we live in.

I think this is also in-part why I am attracted to religious symbolism. I grew up attending Catholic school as well as taking Hindu study courses on the weekend and was sort of inundated with religion for a significant part of my life. Though they are very different religions, as with most religions, they are both chock full of symbolism and beautiful, but often brutal imagery. Religion has this incredible ability to create division, but also offers spaces of congregation. It grants purpose and guidance, but often also strays into judgement and persecution. I am constantly curious about these contradictions, and the ways in which they show up everywhere we look, even as we seek connection and community.

The work beyond the garden wall, (2021), was commissioned by the wonderful Director of Timespan, Giulia Gregnanin and was borne from themes surrounding the history of ‘gossip’ as a negatively perceived “women’s activity”. When thinking about the role of gossip socially, it is part of the histories of oral tradition, folklore, a means to share knowledge and often a way to convey warnings and safety amongst women despite its negative perception. The installation uses textiles, and hand sewing to reflect the craft and trade also historically relegated to the female gender. Bound together by jute, the repurposed carpets reflect upon the necessity of the fibre import in the textile trade, which brought immense wealth to the British Empire through colonialism. The carpets and rugs sit atop an enriched gardening soil, sprouting with Scottish wildflower seeds through the cut out text. Here the sprouts reflect the proliferation of gossip, and the untameable nature of the pollination of information, burrowing beneath the soil and beyond enclosures, immune to containment.

beyond the garden wall, recycled rugs and carpets, wildflower seeds, soil, 2021

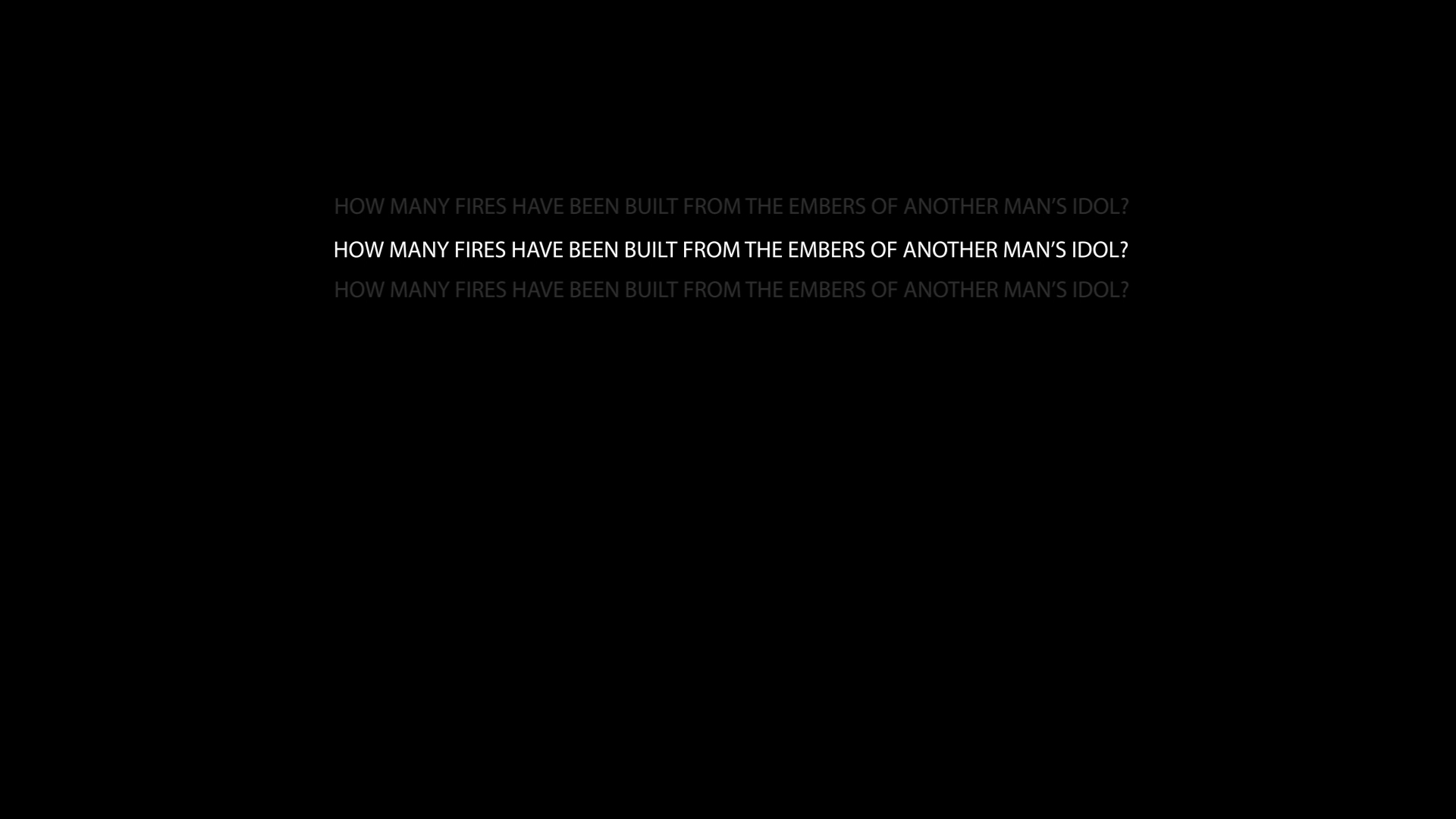

I saw your film, Will their fires keep you warm, (2020), your only film work, as part of a screening night at CCA a few years ago and was struck by the impactful nature of its simplicity. But it’s a really intensely packed work politically— could you describe how the work came about?

I have no technical background in film, but have always been drawn to moving image. We all have cameras in our pockets, we see the mass production and dissemination of video daily, and it has become such a significant and vital part of our social dialogue and communication. It’s how we access and understand different parts of the world at a distance.

At the time I made the work, the ruling Hindu Nationalist party of India, the BJP, had been accused of encouraging a slew of violent acts against religious minorities, in part by the passing of bills that threatened the citizenship of those very demographics. We were witnessing the violence in real time on our phones, and for me it felt like such an evident pattern of abuse, a reflection of India’s colonial past and imposed division.

The work is a short film of a burning pile of sacred cow dung, blessed by a Hindu priest, purchased via Amazon. Smoke swaying to the crescendo of the dawn chorus; layers of British bird calls. It is accompanied by a very personal text I wrote reflecting upon cycles of abuse, both personally and socially. It contemplates inherited trauma, and those things we are often guilty of leaning into as a conviction of our beliefs, or due to expectation. I come back to these themes often, how abuse begets abuse, the almost invisible and intangible ways we internalise violence, and whether or not that damage can be undone.

You’re going to Hospitalfield on residency on Friday! What are you planning on doing whilst you’re up there?

I am really looking forward to my time at Hospitalfield. I am hoping to really expand on, and immerse myself in my writing practice. I have only really explored writing minimally in my practice, or used it as a starting point, but I plan on laying the ground for a little publication. I want to delve further into those intangible experiences and feelings. I have been writing about grief for a few months now, and I often regard my work as a meditative practice, or as a process of mourning. So I suppose this is just another attempt to work through some of that weight and see what comes about.

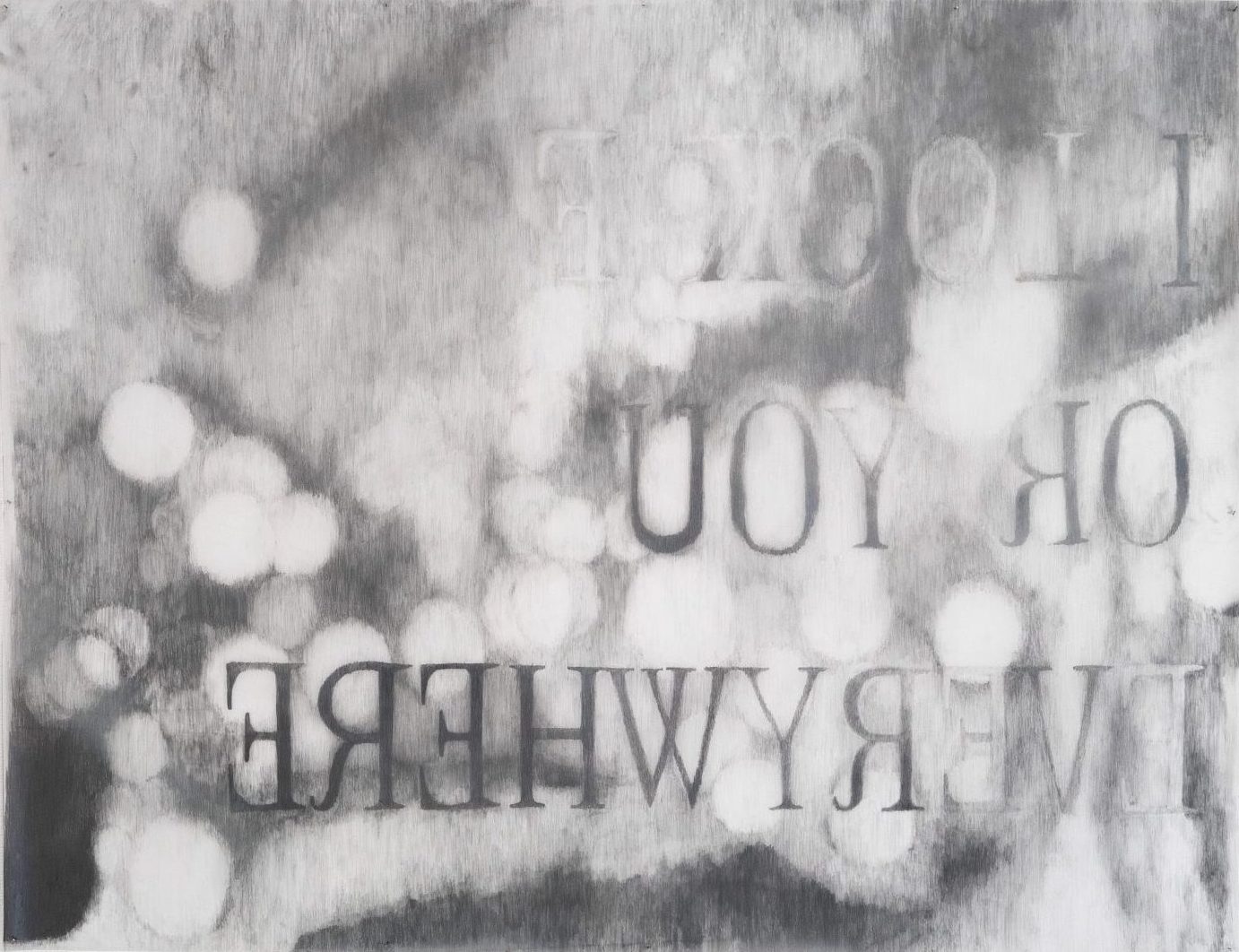

not anymore, graphite on mylar, 2024

How does writing feature within your practice in general and what is its importance?

Well I think writing is possibly the foundation of my practice. Words tend to always be my starting point. I feel as though I often come up with titles first; I am constantly taking notes in one of many notebooks, or on my phone, or underlining quotes in books. I tend to then collect those thoughts by writing down single lines on individual pieces of paper, lay them all out, and see if any of them correspond or speak to one another. Words carry so much weight, and can create such strong visuals, so I like to think of this writing process a bit like sketching. Much in the way I think about objects, what happens when you put two distinct words together? What images develop? More often than not, that is how installation develops in my mind, simply by thinking of the way in which words can create images of new environments or surroundings.

I’m thinking about how your work discusses identity without being overtly about identity, how do you consider and achieve this balance within your practice?

I’m not sure I really do consider it. I think naturally, one’s work when honest is an extension of themselves. I tend to make work about things that sit with me, that cause a reaction in me. Whether that is a memory, an object, a response to social dialogues; my reactions, concerns, and interests are always going to tie back to my experience in some way. (As they do with most people I think). I am not overly concerned with people understanding me through my work or even alluding to identity. I hope to simply offer a perspective or a consideration; to share a viewpoint. Maybe to allow other people to see themselves in the work, even if only a little.

will their fires keep you warm, [film still], video, 2020

—

Anika Ahuja is an interdisciplinary, Indo-Canadian artist originally from unceded Tiohtià:ke (Montréal, Canada). Since receiving her BFA from Concordia University in 2014, her work has been included in group exhibitions across Canada and the UK. She was also awarded the Sonia de Grandmaison Endowment as part of the Emerging Artist in Residence program at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity in 2018. Her work was also included in the 2020 UCLA New Wight Biennial in Los Angeles, CA. Whilst working as a committee member for Glasgow’s Transmission Gallery from 2021-2023, Ahuja was also awarded a 2021/22 Visual Arts and Craft Maker’s Award by Creative Scotland and Glasgow Life. She has since received the Eaton Fund Artist Grant in 2025, and is currently completing the Interdisciplinary Residency at Hospitalfield in Arbroath. She continues to live and work in Glasgow, Scotland.

-

anikaahuja.com

︎ @anikaahuja

caitlinmerrettking.cargo.site

︎ @caitlinmerrettking

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Chaney Diao.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED