Arpita Shah

Interview by Ruth Millington

-

Published in November 2022

-

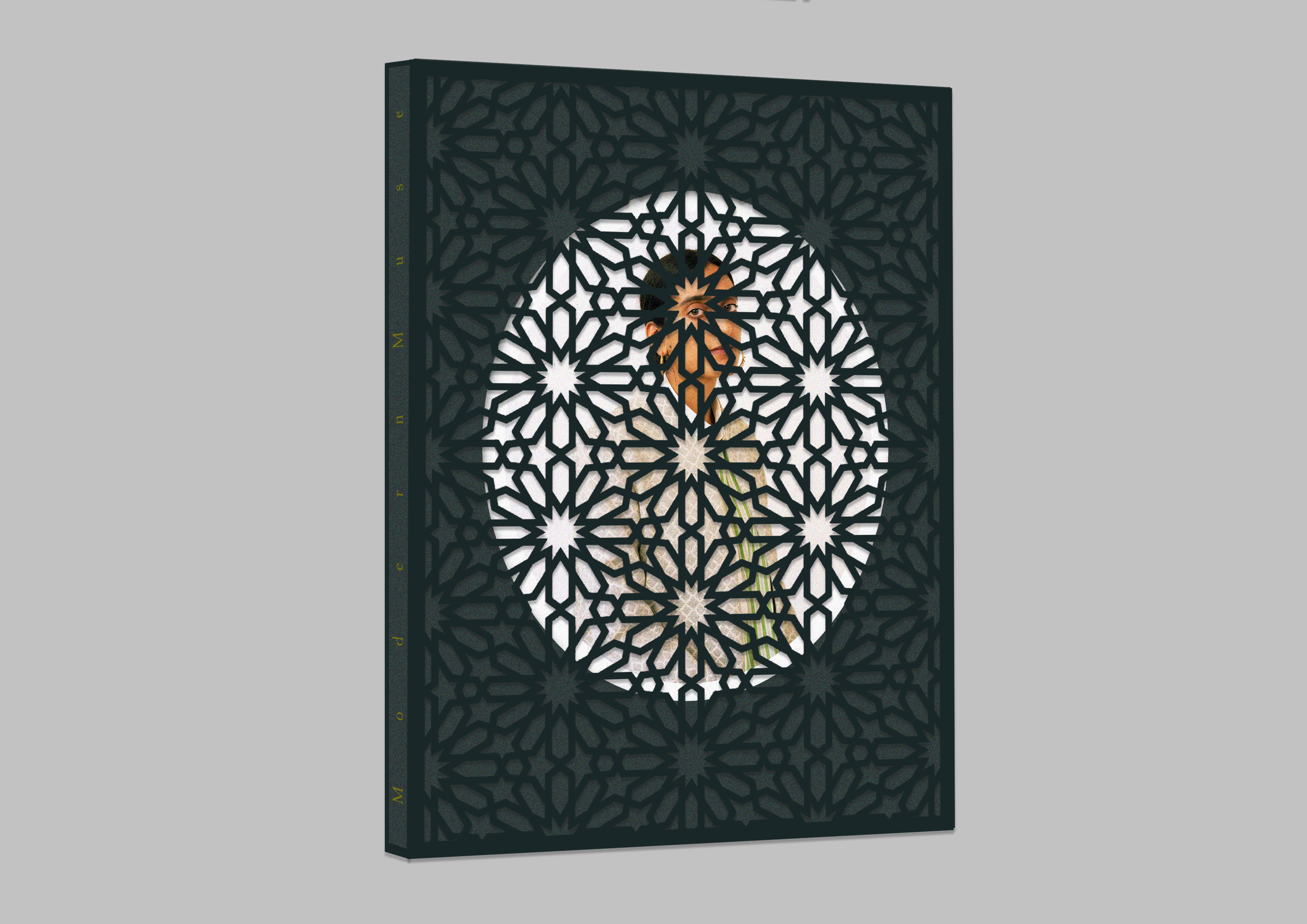

Working between photography and film, Arpita Shah uses her lens to interrogate the intersection of culture, identity and heritage. Frequently turning her female gaze on South Asian women, she explores and celebrates their narratives, which are often woven into the fabrics they choose to wear. Shah spoke with art historian and author Ruth Millington about her series ‘Modern Muse’, commissioned by GRAIN in 2019, with the support of Arts Council England, and recently acquired by Birmingham Museums Trust.

-

Let’s start with the term ‘muse’. Today, it carries pejorative connotations of a passive, female nude. But what does the word mean to you and why did you title this series ‘Modern Muse’?

Although the female ‘muse’ has often been portrayed in art history through the male gaze, I’ve often referred to my mother as my ‘muse’ as I’ve been photographing her from the very first moment I picked up a camera. Many of her experiences and childhood memories have inspired the work I make and have shaped the relationship I have with my own cultural identity. A ‘muse’ therefore represents powerful brave women, like my mother and grandmother, who inspire with their words, creativity and life experiences.

As a photographer, I’ve often referenced Hindu mythology and Indian paintings to explore the experiences of the South Asian diaspora, often drawing from images of Hindu goddesses emerging out of great big lotus flowers, and depictions of women and flora from Mughal and Ragmala miniature paintings.

When I was researching for ‘Modern Muse’ I was really drawn to paintings of Mughal emperors and how they were positioned and framed. At the same time, I discovered how rarely Mughal women were painted based on what they looked like but were often idealized archetypes of beauty. Historically, Mughal women did play crucial roles in that period, however they were often sensually portrayed, as a consort or a lover, through the eyes of a male artist.

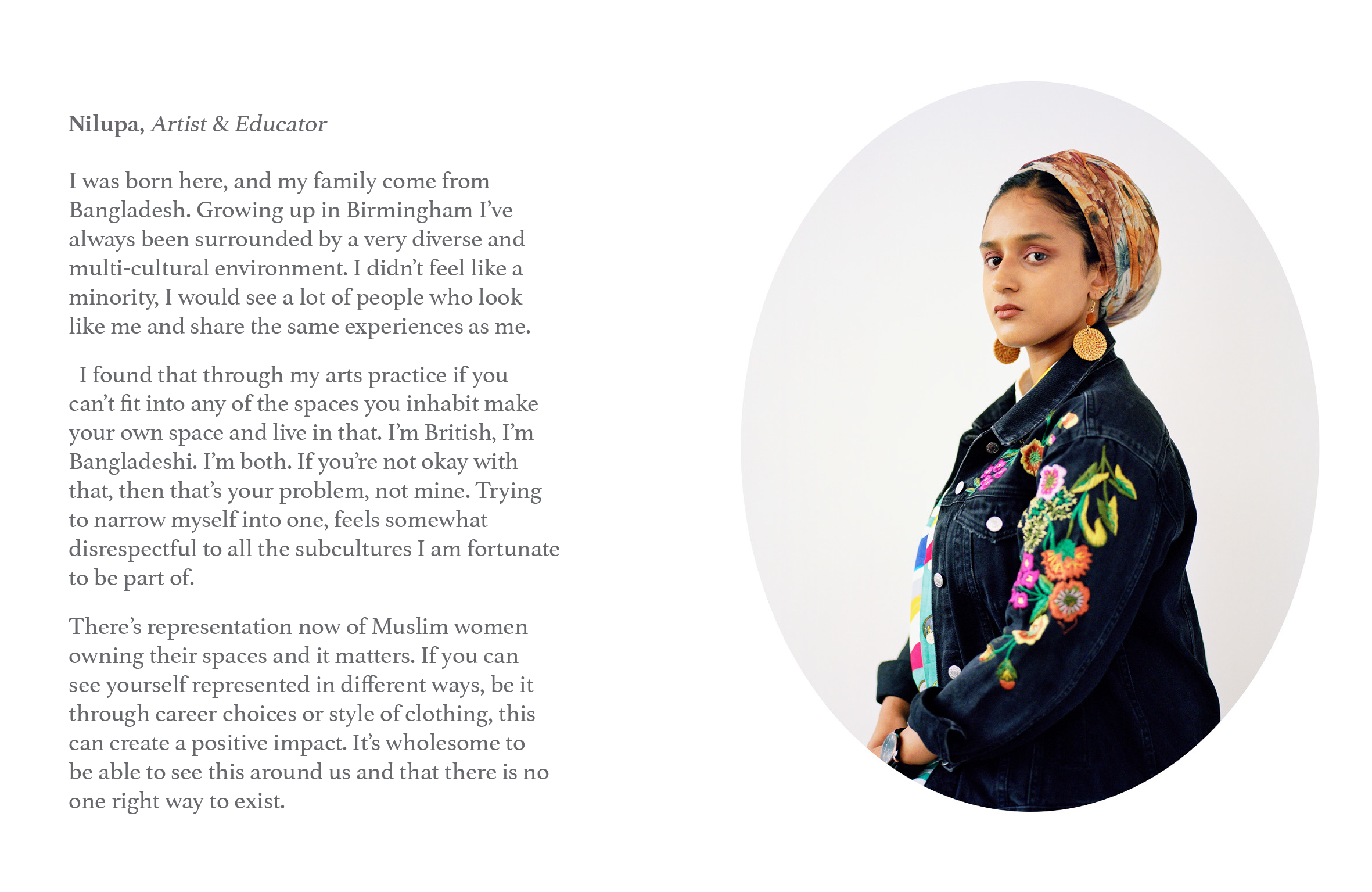

Through ‘Modern Muse’ I wanted to challenge these narratives, so chose to deliberately replace the Mughal emperors with portraits of modern British Asian women. I also wanted to reframe Western notions and traditional representations of the ‘muse’ through portraits of powerful and inspiring women of colour, who have something to say.

Your muses are all British Asian women, living and working across Birmingham and the Midlands. How did you select and approach them for this project? Can you also talk about your relationship with them, including their role in both sitting for their portrait and providing text to accompany their image?

I met many of the women I photographed as part of ‘Modern Muse’ on social media, some of whom I already followed as I was a fan of their work, and others after sharing an open call for the project. It was incredible to have so many diverse women getting involved.

My muse ‘Haseebah’ was the first woman I approached and photographed for the project. I met her at the Asian Woman Festival in Birmingham in 2019, where she told me about her arts practice, and was instantly drawn to her; she has this incredible magnetic energy and style.

Prior to all my photo sessions with each of the women, we had conversations about the concept and project themes. As the work focuses on British Asian identity, I asked them to bring in clothes that best represented their style and their identity. Many of the women wore traditional Asian garments or Western clothing, or a combination of both.

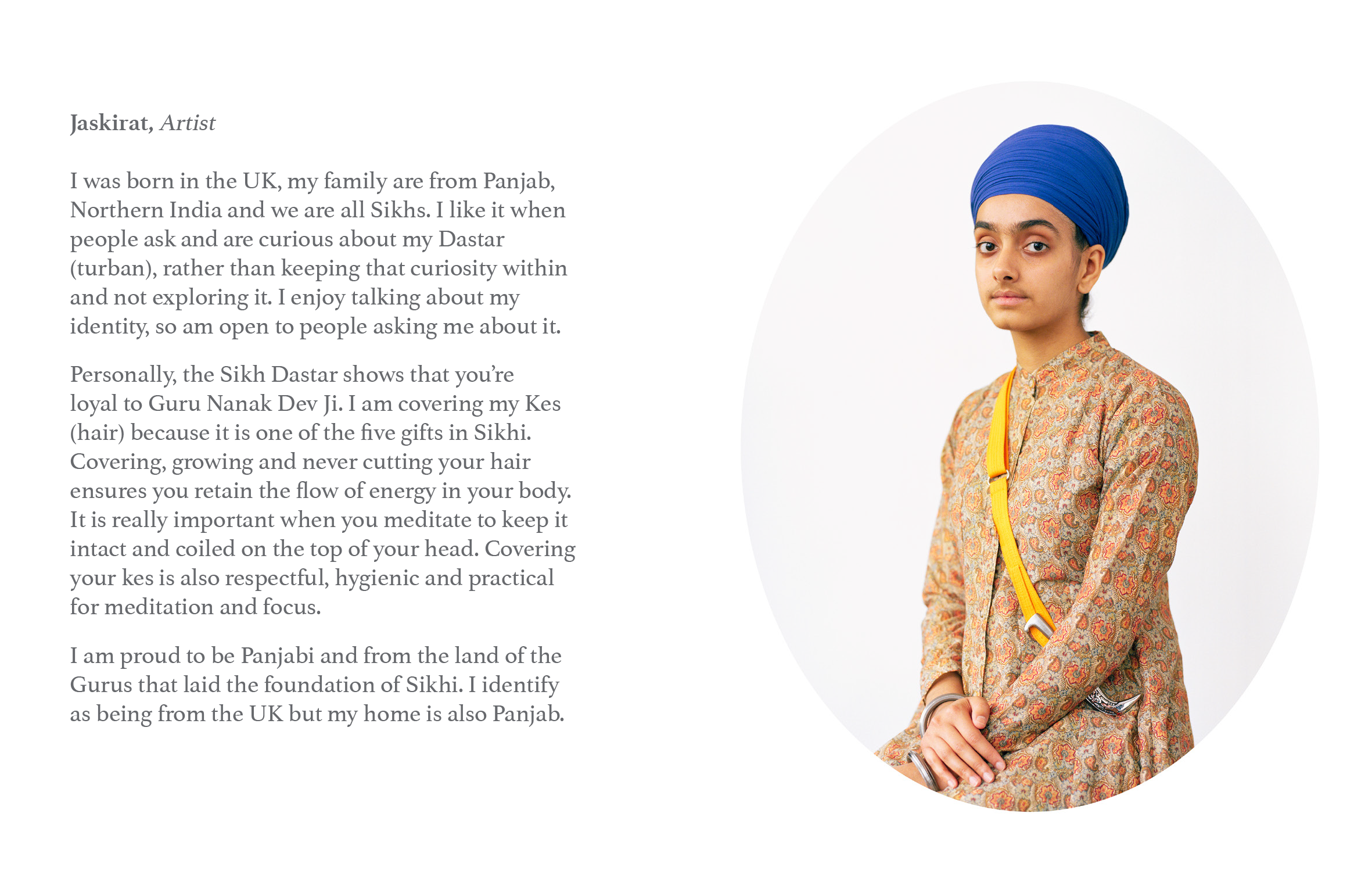

Before making the portraits, I also recorded conversations with each muse, who discussed their feelings about identity, heritage, family and home. Excerpts from those conversations sit alongside each muse’s portrait. At every stage of the project and process of editing for the book, I have been in dialogue with all the women involved.

It was also crucial to give agency to the women through their gaze, so I asked them to look directly at me through the lens, titling the camera angle up so as to elevate them.

Many of your muses, in earlier series such as ‘Purdah – The Sacred Cloth’, as well as this body of work, wear headscarves in their portraits. Across art history, as well as the media, this item has been at the heart of polemical debates. What are you, and your muses, trying to contribute to conversations around veiling?

I grew up between India, Saudi Arabia and the UK, where the tradition of veiling and head covering have very diverse histories and varied personal, political and cultural meanings. It is such a complex subject matter and in Purdah – The Sacred Cloth I really wanted to focus on some of it’s varied traditions and meanings within the UK’s South Asian community.

As part of the project, I initially ran photography workshops, which invited the women to bring in sacred objects that reflected their cultural identity and heritage. Many of the women brought in fabrics such as a sari, shalwar kameez, hijab, dastar and chunni, all which had really personal stories attached to them. As we discussed the significance of each cloth, many of the women also reflected on the dominant narratives we see around veiling and head covering in the media and how that impacted them and the negative stereotypes they’d experienced.

So through Purdah – The Sacred Cloth, I wanted to address these common misconceptions through the portraits and words of contemporary Sikh, Muslim and Hindu women who practice the tradition of head covering. Visually the portraits drew from 14th Century Dutch paintings (Rogier van der Weyden: Portrait of a Young woman with a Winged Bonnet & Robert Campin's Portrait of a Woman, c. 1430-1435) because I felt it was important to reference the history of the veil in West. Variations of the veil were often worn in Europe in the Middle Ages and I wanted to work to comment on the fact that it is not only a tradition associated with the East.

Modern Muse also includes South Asian women wearing a dastar and variations of the hijab, while featuring South Asian women who do not follow the tradition of head covering. As an artist I’m fascinated with the way younger South Asian women express their cultural identities. Many of the women who do wear headscarves commented on how open they are to discussing them and were so generous in sharing their relationships to them. I hope both projects enrich the viewer’s understandings of the significance and unique meanings that each headscarf can represent, and break down certain presumptions they may previously have had.

Congratulations on the recent acquisition of ‘Modern Muse’ by Birmingham Museums Trust (BMT) a museum that houses a world-leading collection of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, featuring many traditional muses. What does it mean to you that this series will be displayed on their walls?

It feels quite incredible to have a selection of portraits from ‘Modern Muse’ acquired by Birmingham Museum Trust and become part of Birmingham’s permanent collection, the home to Rossetti’s ‘Proserpine’ and Bunce’s ‘Musica’.

As a South Asian woman and a female artist, when I was growing up and studying photography in the UK, I didn’t see many women like me, my mum or grandmother, or our histories represented in museums and galleries. So, making and exhibiting work about South Asian female identity has always been something that has underpinned my practice for the past 18 years.

Many of the women from ‘Modern Muse’ are from, or have very strong connections to Birmingham, which makes this acquisition feel very special and very relevant. It’s so important for museums to reflect the diverse voices within their own communities.

Both museums and photography have very complex histories relating to representation, power and the colonial gaze. So for me as a South Asian woman, BMT acquiring portraits of contemporary British Asian women, photographed by a British Asian woman feels very much like a pivotal moment in my career, which I’m so proud and grateful for.

How would you like ‘Modern Muse’ to be considered by museum visitors?

I hope that through viewing the portraits and reading the words of each muse, visitors will gain more of an insight into some of the diverse perspectives and narratives of British Asian women, which may challenge existing notions they may previously have had.

I also hope the series will help reclaim and reimagine their ideas of the meaning of the word ‘muse’, encouraging visitors to reflect more upon it’s origin within Greek mythology and how it had originally been used in reference to Goddesses, who were also sisters, imbued with divine power, knowledge and creativity.

As a South Asian artist it was important to challenge representations of South Asian women in Mughal Indian miniatures, but also comment on the visibility of women of colour in Western representations of the ‘Muse’. I made ‘Modern Muse’ for South Asian girls and women, for them to feel represented.

I hope more than anything that this series of portraits and each muse’s words will resonate with some of the museum visitors and inspire them – in the same way each muse has really moved me.

-

Modern Muse was commissioned in 2019 by Birmingham-based arts organisation GRAIN. To purchase a copy of the Modern Muse book, please visit GRAIN’s website: grainphotographyhub.co.uk/portfolio-type/arpita-shah/

-

arpitashah.com

︎ @apritashah_

ruthmillington.co.uk

︎ @millington_ruth

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Tal Regev.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED