Charlie Godet Thomas

Interview by David McLeavy

Published June 2014

-

Charlie Godet Thomas works within the field of sculpture, video and with the digital image. His works use the physicality of materials to suggest a certain potential and to employ simple yet complex gestures.

-

Your work seems to employ minimal gestures, or at least it appears to consist of a fairly stripped down aesthetic. Is this something that is important to you or is it just the natural by-product of the more conceptual aspects of your practice?

In part this is because I am an indecisive person, my making process relies heavily on creating strategies and rules in order for me to make decisions. I find it easier to remove things than to add them, with reduction there are only a certain list of elements that can be reduced, I can go through them and stop when I am happy with the results. Untitled (At Best the Poet Can Prepare Traps), for instance, starts with observation as opposed to expression. I have heard works such as these described as metaphor, but they are simpler than that, they are testament to looking and noticing. In this case presenting a reduced form is a strategy that brings to the fore something that I want to draw attention to, the way broken glass gathers in the corners of the streets on a Sunday morning. My interest in reduction as a method for making is also informed by my interest in poetry as a form, simultaneously concise and an opening up of possibilities.

Royal College of Art MA Degree Show, 2014

I am interested to know more about how you approach the physical elements of your work. The piece you exhibited recently at Toast Manchester as part of Cactus Gallery’s offsite project provides an interesting relationship between two very different physical components. Is the materiality and physicality of things often a factor you consider when making new work?

Considering the materiality and physicality of things is very important. My method is to play materials off against each other so as to animate something that is otherwise motionless. I remember visiting the Rodin exhibition at The Royal Academy, London in 2006 and being fascinated by the way that a work like Monument to Balzac could be at once so still and yet charged with potential action, Balzac’s foot slipping suggestively from the plinth. This is a quality that I have tried to push in my own practice. Take for example Untitled (Left Obscure), the work is not figurative (explicitly) but the tension of the drum, wedge and photographic print cast in rubber suggest a great deal of bodily weight and potential movement. In these works there is a photographic concern, which is to do with stillness in photographic images, I use materials in order to combat that feeling of stillness.

Untitled (Left Obscure), silicone rubber, c-type, paint, varnish, wood, door wedge, 500 x 700 x 500mm, 2013

You mentioned how your interested in movement in your work or the suspense that is gained from maintaining a potential for movement, and I am interested to know if you feel this suspense would be lost if the work actually moved in some way.

I think that my interest is not in movement as such, but in an insinuation that everything might change suddenly, as though the work might undo itself. The heavy rubber print might roll off of the drum, or the small fragment might continue to sink into the fabric until it is no longer visible. If any of that actually played itself out the tension that is inherent in a state of pause would be lost. It occurred to me recently that this quality is related to my fear of falling, something that has stayed with me since witnessing a man jump to his death in 2005.

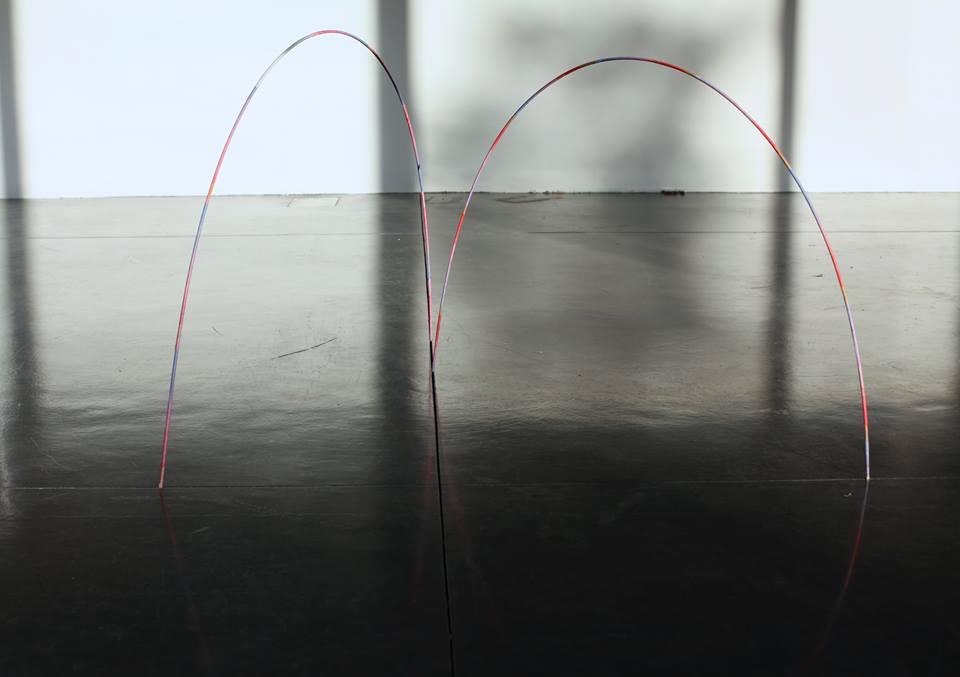

There are less corporeal (and morbid!) pieces, which have a different relationship to movement, these are flexible collaged wooden dowels, an exercise in putting photographs to work as sculptural drawings. The architecture of the space becomes integral to how the individual pieces can become animated. “No” / “Yes) for example, draws attention to the way that the floor in that particular space was cast in slabs, allowing two arcs to hold themselves taught in the spaces between floor-sections.

Untitled (At Best a Poet Can Prepare Traps No.1), Wood, paint, broken glass bottles, 800 x 100 x 600mm, 2012

I want to know more about your selection of imagery and pattern on some of the fabric and digital print works. How do you decide what colours or imagery to use?

I have an extensive archive of 35mm photographs, however there are only two images that I use as points of departure for works. It doesn’t seem right to reveal exactly what the photographs depict, but suffice to say that they are images of biographical significance. The process of reworking and revisiting an image is not a search for reason or understanding, but rather a manifestation of denial. Repainting and reconfiguring the image in the way that I do is an attempt to transform it so that I can enjoy it as colour and form, whilst failing to achieve that aim is reason to continue working on the series.

The most long-standing is the Sateen Dura-Luxe series. The title refers to a brand of house paint used by a fictional Abstract Expressionist in Kurt Vonnegut’s Blue Beard. The artist, Rabo Karabekian, creates a significant body of work only to discover later in life that the paint in question is toxic and turns to dust within a few years leaving him, essentially, with nothing.

In terms of mark making and colour selection, my earliest influences come through, namely Graham Sutherland and Francis Bacon. The first painting I ever remember seeing was Three Studies for Figures at The Base of a Crucifixion. I am always struck by the way both Sutherland and Bacon managed to use such jovial colours communicate total despair, I think of it as a balance akin to the genre of tragicomedy.

"No" / "Yes", wooden dowels, laser prints, glue, 900 x 5 x 900mm, 2012

You mentioned tragicomedy and how that is something that you are interested in with the work of Bacon and Sutherland. Is there any comedy in your work or approach?

I didn’t mean to say that Bacon and Sutherland deal with tragicomedy, but that there is a playing off of one thing, colour, against another, content. Tragicomedy is a genre of balance, and that is something that I have been thinking about a lot recently, that it is important to readdress balances across the practice as a whole. I read an interview with Beckett in which he says, ‘All that matters is the laugh and the tear’, the succinctness of that statement really struck me.

Sometimes the work can be comic, or flippant. For Poppositions Art Fair I sold the cast rubber lemons by weight according to the local price of real lemons. Once all the paper work had been done my share of the money was £0.27p, minus the cost of materials and shipping. I have also just submitted a proposal for Frieze Projects to paint all of the black railings in London white, no reply as yet. At the other end of the spectrum you have Blues Poem , the work I made for Bending Light at Home-Platform. This piece is the first in a series exploring the interior monologue of a distressed and inebriated fictional poet.

What do you think the role of the artist is?

There are lots of different roles that artists assume, some more responsible than others. For me the paramount thing is to approach your practice with sincerity and authenticity.

Untitled (Sateen Dura-Luxe No.3), silicone Rubber, frame, paint, C-type, 950 x 1300mm, 2014

So what is next for you?

This month I'm showing at The Bermuda National Gallery as part of The Bermuda Biennial 2014, Bermondsey Projects in Dizziness of Freedom curated by Mette Kjaergaard and The MA Degree Show 2014 at The Royal College of Art. It has been a busy year, once those shows have closed I am hoping to take a deep breath and enjoy being in the studio without any impending deadlines.

-

Charlie Godet Thomas lives and works in London. Recent exhibitions include Blinding Light, Home Platform, Bristol, The Bermuda Biennial 2014, The Bermuda National Gallery, Bermuda and Dizziness of Freedom, Bermondsey Project Space, London.

If you like this why not read our interview with Mark Riddington

-

© 2013 - 2018 YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED