David Lisser

Interview by Lizzie Lloyd

Published October 2017

-

In The Box Gallery at the heart of We The Curious – Bristol’s centre for science and technology – is David Lisser’s exhibition, ‘The CleanMeat Revolution’. From the vantage point of a fictional future, the exhibition looks back at the period around 2030–2080. The show presents artefacts excavated from an imagined past, documentation of protests that haven’t yet materialised, and mechanisms for producing novelty meats called things like Neander-Thighs and Diplodocus Dippers. I spoke with David Lisser about this new body of work to find out how plausible his vision of the future might be.

-

Let’s start from the beginning. How did your interest in the future of food develop?

I have a longstanding interest in food, science and technology. In terms of food, obviously it’s a vital part of life but the way that we eat food is both radically different around the world and exactly the same. To be invited to share a meal with someone is everywhere either a sign of an existing relationship or an invitation to form a new one. Food is part of who we are and how we communicate. I’m interested in this social side of physically sharing food.

Over the past few years I’ve also become interested in food production and supply chains, really exciting stuff like that! I started zooming out and thinking about the way the world produces food: who it goes to, how, why, what gets wasted along the way, and how the climate is changing the way that we do it.

Right to Rain Protest T-Shirts

So your exhibition, ‘The CleanMeat Revolution’, is about what food – its consumption and production – says about a society?

Yes. The Arts Council funding bid which I was awarded, in partnership with Pervasive Media studio, gave me the opportunity to spend a long time just buried in fairly dry research: reading UN, World Bank, and food and agriculture reports; looking at how we’re going to keep on producing food and for whom. I also had many fascinating chats with other PM studio residents, ran workshops and spoke directly with specialists – a futurologist and archaeologist – as well.

All this led me to think about how the people of the future will perceive us. And then I started to think how we could imagine the future as if it were history, what would the future think of this speculative history that I’m setting up? It gave me an interesting angle to come at the material from, allowing me a bit more imaginative freedom.

Lots of the things that you’ve talked about being interested in are quite dry (reading documents, reports etc). This is quite a difficult form of research to translate into objects that are compelling, aesthetically, in their own right. Was this a concern for you?

Yeah, I suppose a lot of the time when I’m doing this dry research I’ll be asking myself: so what does this look like? If this weird thing happens where the Mediterranean dries up and Siberia and Northern Canada become wet, due to permafrost melt and we can grow crops there… how will it physically change things? Things like the image of the world from outer space. The architecture in these places will change too, along with the people that live or migrate there as a result of these changes.

So in the case of lab-grown meat, at the moment it’s all done in petri dishes, but what will it look like when we get it to a point that it is economically viable and commercially available? Will it happen in big vats? Or in bio reactors? How will it be marketed? I’m interested in how the idea of lab-grown meat becomes manifest, physically.

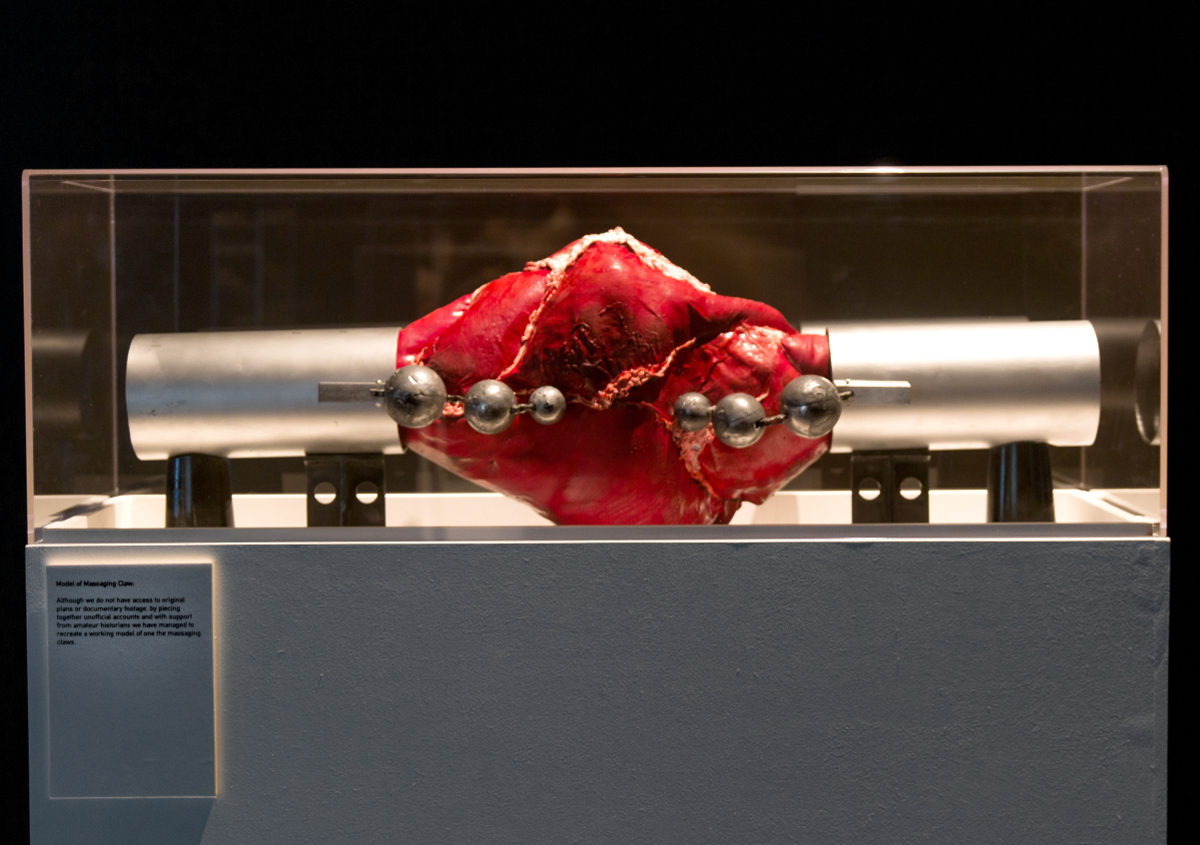

CleanMeat massaging artefact

There’s quite a strong sense of inherent materiality in meat isn’t there?

Yeah, for a long time I really resisted focusing on meat but I kept getting drawn back to it. Despite some decline in Britain over the past 10 years, on a global level we’re buying more and more meat. This is primarily because of nineteenth- and twentieth-century ideas about what constitutes food for the rich and food for the poor. It’s also related to the changing financial development of places like India and China. So, for example, if the citizens of India and China – those who do eat meat I mean – continue to increase their consumption of meat, as they have been doing recently, then we are going to have to find a new or different way of making meat. The alternative is to try to convince them not to eat meat but that has a whole lot of political repercussions in which the traditionally meat-eating West turns around and starts telling other people not to do it.

Malfunctioning Fridge Console

You touch on a lot of this in the spoof documentary/educational film/lecture in the show. But as a viewer, because I’m aware that I’m watching this in the context of a speculative snapshot of the future, I’m not sure how much of what you are telling me is true and how much is fiction.

Yes, that’s true – sorry about that but actually I’m quite pleased to hear you say that!

I think it’s really interesting, to merge realities, speculations and histories.

In fact, I don’t think that there’s anything in there which is entirely made up. Everything has some bearing on what has already happened or is happening now. I’m just imagining their potential future development. Except maybe the cloudburst – I did make that bit up!

I love the idea of the cloudburst! What is it in your mind

It’s the data cloud reaching its limit. I like the idea of the data cloud – it’s quite poetic isn’t it? It makes me wonder, what does it mean if we have a downpour? What do we do with the data that we no longer have access to, for whatever reason? Does it end up in the digital equivalent of the sewers? Basically, I’m wondering what the data version of the water cycle is.

Most of the ideas in the exhibition are real, then. Even the artificial exercising of meat, a model for which is in the show, that’s real too?

Yeah, that’s true, I mean, it probably doesn’t look like how I’ve made it look. The thing about this ‘clean meat’ is that it currently has very little texture. At the moment it’s all processed like a burger or a sausage. But if you’re growing meat outside of an animal, you’re growing tissue rather than meat so it’s texture is mushy. Physically and chemically it’s flesh but it doesn’t have any of the things that we associate with meat in terms of its bite, how it feels in the mouth. And that’s because it’s not exercised.

Artisanimal Micro-carnery

Artisanimal Micro-carnery, (detail)

That sounds disgusting! I’m not vegan, or even vegetarian, but listening to all this I can’t help wonder why we don’t just stop eating meat altogether?

Well, yeah, that would probably be my choice too – or hugely reduce our consumption, but this ‘clean meat’ thing is definitely happening. In the last month or so Richard Branson and Bill Gates have both publicly come out to say that they’ve put a lot of money into this kind of research. And Silicon Valley has picked up on it too. I hesitate to speculate but I think in the next 10 years or so it’ll be out there and commercially available.

But clean meat isn’t just of interest to the food industry because our supplies of meat aren’t meeting the levels of demand for it. Associations like PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) are really interested in it as well, for obvious reasons.

Do you see the meat that you eat in a different way now? Have you cut down a lot more since starting this project?

Yeah, I have. Mainly as a result of my initial research. Animal agriculture is responsible for around 17% of anthropogenic greenhouse gases, which, depending on who you ask, is roughly equivalent to, or a bit more than, global transport emissions. It’s still less than burning fossil fuels for energy though, so that great! A lot of this is because of cows so I haven’t eaten beef since I started this research.

Model of CleanMeat Massaging apparatus

To what extent do you intend your show to be a catalyst for changing or impacting the behaviour or the habits of your visitors?

I don’t know. I’m just trying to get people to think about something from a different point of view. So the idea, in presenting a potential future, is that, if what you see in that future jars with you then maybe you’ll do something about it or think about how you might live in that future. But I don’t think I have a single message about meat production in particular because it is actually a very nuanced area. When cared for well, and with a lot of land to graze on, and in non-intensive environments, livestock can be a very beneficial part of the ecosystem. So the issue isn’t black and white. As far as being a catalyst for change, that sounds too much like an agenda. Maybe a prod or a nudge is more what I’m after.

Art that has an environmental or social message can tend towards the worthy. It feels like in your show you use humour as a way of ward off that risk.

Yeah, that has definitely been something I’ve been worried about when tackling this material. Often when people see what I’m working on the first question to me will be, ‘Do you eat meat then?’. But it doesn’t really matter what I’m doing. That’s not the point here, I’m not trying to preach.

But yes, humour is a great leveller; you can say a lot more if you say it as a bit of a joke. It’s like the idea of the novelty meats: some people think that it might theoretically be possible to make a dodo burger sometime in the future because the whole genome of the dodo was sequenced last year. This icon of extinction, which, let’s not forget, died out due to humans over-hunting in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, could be brought back into the food chain. Bringing back this bird that we over-ate, just to eat it again, seems to me like perverse satire.

Humans do some funny things don’t they?

Ossified CleanMeat

Lots of your humour comes about through your explanatory wall texts and gallery labels rather than through the objects themselves which are displayed quite seriously, set out as we might expect of a traditional museum. In fact, the aesthetic that you’ve gone for is very specific. For me it recalls the seventeenth-century Spanish still-life paintings of Juan Sánchez Cotán and Francisco de Zurbarán with their black background and dramatic lighting. Or even memento mori. Are these references made consciously?

I like memento mori – they’re fascinating paintings of collections of objects including things like skulls and hourglasses. People would have them on their walls as reminders of their inevitable death… that’s quite a remarkable thing to live with! I’m fascinated by a society that sees it as a sign of your wealth and intellect that you are aware of your own mortality. I don’t think we really do that now! I also love Mat Collishaw’s series Last Meal on Death Row (2011) in which he photographs a series of meals chosen by inmates to be their last. I hadn’t really realised it but I wonder if they were in the back of my mind while I was doing this project and thinking about food and death. Given that meat, ordinarily, as we know it, involves death, thinking about mortality and food goes hand in hand.

When I was in the show, it really struck me that there might be a novel in there. The world that you’ve created feels very complete including specialist micro-industries, rain protests and devices for measuring individual supplies of meat, for example.

Do you know what, you’re the second person to say something like that to me. I don’t really write but in this case I did write myself a little history to work off. I was very concerned that I didn’t want to just present an incoherent mess of possible things.

Narrative really helps too. I think that, along with humour, you can say a lot more when you also have a story to tell. Stories are an ancient way of relaying information: if you have a story to tell people will listen. I’m hoping with this show to bring people on a bit of a journey that is about our world, but not directly.

So is this show, as a whole, a metaphor for something else?

Not really directly but it’s all about human behaviour and what we want technology to do for us and whether or not that’s a good idea. Cloud seeding for example, is happening, sort of, but I take it to an extreme.

What is cloud seeding?

In the exhibition I reference it in relation to imagined rain wars. Cloudseeding is where you sow particular particles into the air – either with aeroplanes or rockets – which help condense water vapour and encourage clouds to form. China used it to ensure a dry night for the opening of the 2008 Beijing Olympics and continue to do so on national public holidays.

I can’t believe that we’re putting this kind of technology to use in this way, essentially for the sake of convenience… used elsewhere it could save lives.

Exactly. And that leads on to an argument about rights, more broadly: Who owns the air? Who has the right to release chemicals into it? Who has a right to rain? Who has a right to consistent weather and to what end?

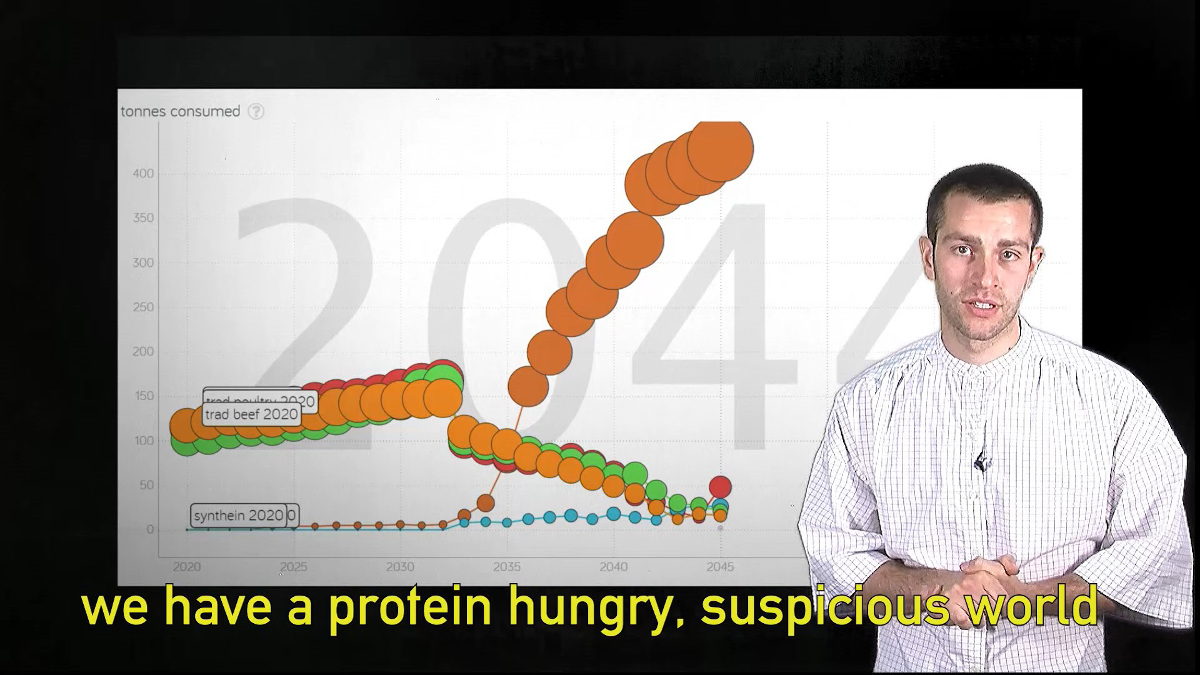

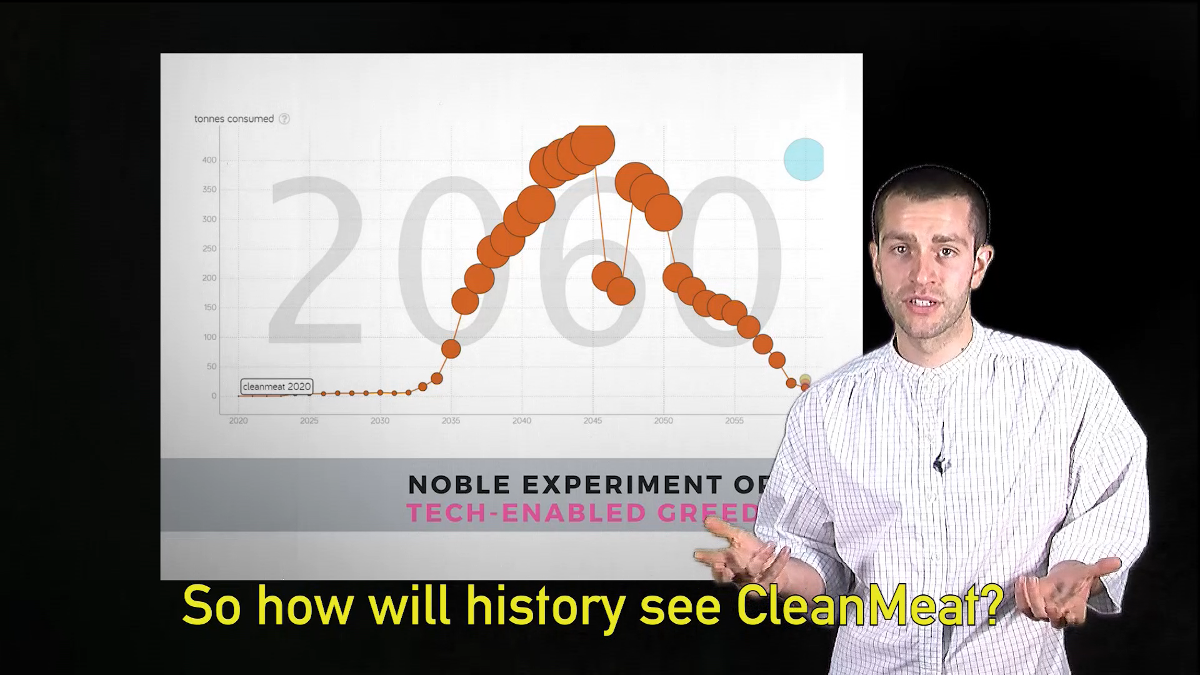

There’s a longstanding historical tendency that sees the political, economic and ethical implications of decisions made by richer governments being to the detriment of poorer countries. The poor always bear the brunt. So, when it comes to behaviour, I’m interested in whether this clean meat idea is a noble experiment or tech-enabled greed. The thing about human innovation is that it could go either way – it could clean things up or it could make even more of a mess of things. The vital question is: should we make things differently or should we live differently?

Still from ‘foods that changed the world; cleanmeat’ lecture

Still from ‘foods that changed the world; cleanmeat’ lecture

Do you see any hope for the future of food consumption and production then?

Yeah, I mean there are good things happening on a small scale like researchers in Manchester who have found a way of desalinating sea water to make it drinkable using a substance called graphene, for example. There are also beef farmers in Australia who follow what they call ‘holistic grazing’, which, horribly simplified, means that they keep their cattle roaming rather than staying in one place. In doing so, they appear to be improving soil quality, increasing carbon capture and reducing reliance on fertiliser and animal feed. I don’t know if their model would translate to smaller countries, or indeed huge herds, but it is encouraging.

So yes, I guess I didn’t want fall into the trap of imagining a wholly dystopian future but wanted to keep utopian and dystopian views of the future in the balance.

Do you think the way in which you present the work as a museum piece helps maintain that balance? Because the story of your future history is told with a sense of emotional detachment, it separates your personal opinions on how we should or shouldn’t live and the moral implications of those choices, doesn’t it?

Yeah, I think I am trying to find a way of talking about this in terms that are, not impartial, but factual, to neutralise things slightly.

So is this whole idea of the speculative future history a bit of a red herring? It’s actually just a framework for you to say something else?

Not sure it’s a red herring, but yes, it’s a device. If you ask people about how they envisage the future, about what they are worried about and what they hope for, it’s often a really good indication of the things that they are thinking about right now. Our contemporary concerns so often manifest and grow into the future.

-

David Lisser, The CleanMeat Revolution is at We The Curious, Bristol until Sunday 8th October 2017.

www.davidlisser.co.uk

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Bob Bicknell-Knight

-

© 2013 - 2018 YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED