Duncan Poulton

Interview by Gaspar Willmann

-

Published in November 2022

-

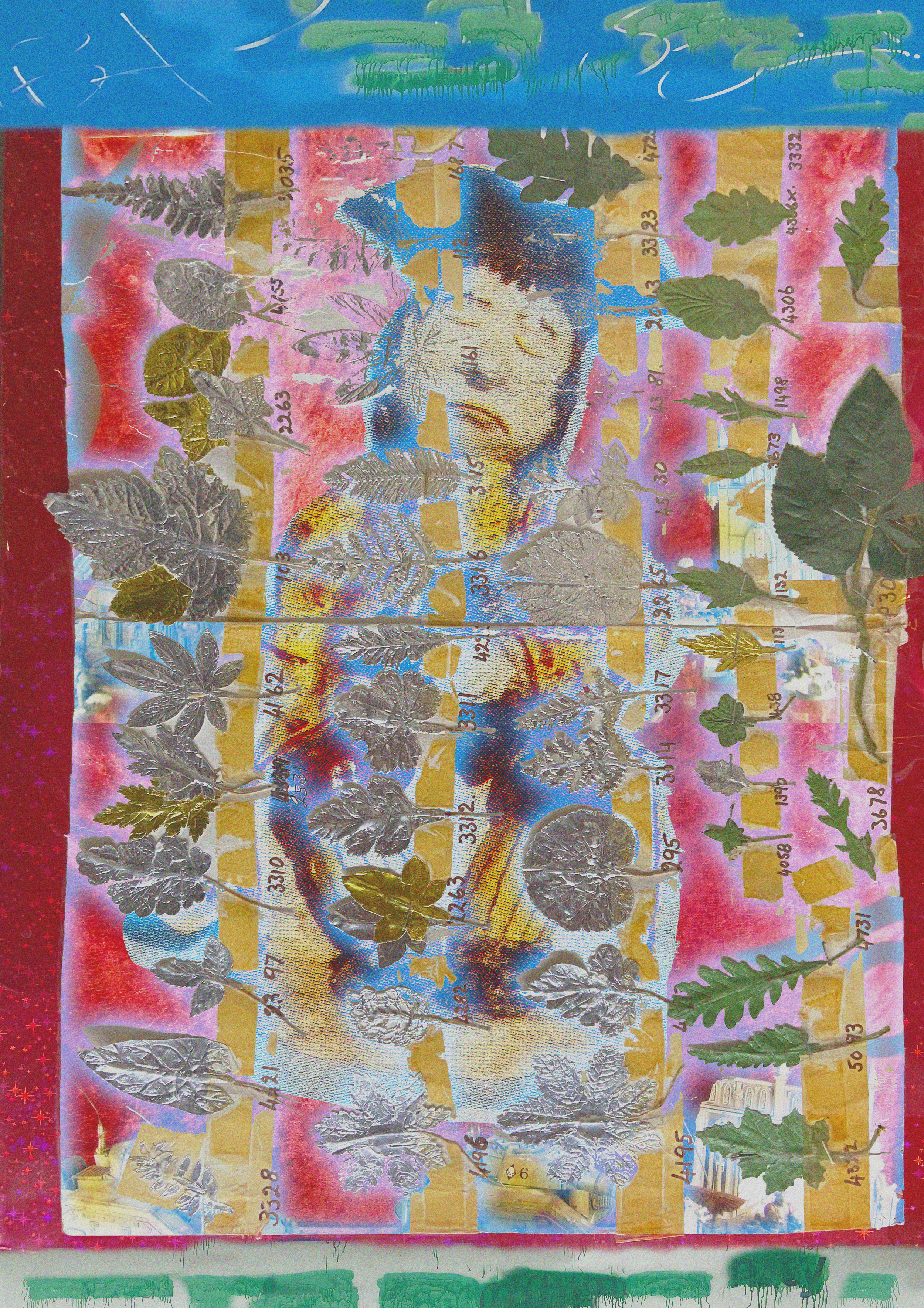

Many Happy Days, 2019/22, digital collage print on archival paper on custom-made cardboard box, 594 x 841 x 100mm. Photo by Max Colson

Hello Duncan! I wanted to start the conversation with a simple question. We both grew up in the beginning of 2000s in this « new » computer world, but during our youth the internet wasn’t really what it is now. Before it became this attention catching total capitalist device, I have some memories digging into a strange internet field, where things were ugly and not limited to 5 websites. Do you have a memory of your first image, or video you saw online?

Hi Gaspar! I’m trying to think back to my youth… I think I’d have been at school when I had my first forays into the world of computers – quite impenetrable things like lessons on Excel, or early educational games like Logical Journey of the Zoombinis (1996) – but I don’t remember getting online really until we had a home PC. I remember the first night me and my brother discovered BitTorrent, and just the bizarre, game-changing feeling of being able to think of a song and immediately play it, to ‘own’ it even. I didn’t have a mobile phone til I was about 14, and didn’t have a laptop until I was in my early 20’s–so most of my online experiences were in the stationary confines of a desktop. This notion of the internet as a more stationary, studious and durational thing has stuck with me. It must shape how I approach it now in my art practice.

The internet just seemed to slowly seep into life. These incremental changes obviously now add up to most people being utterly reliant on an internet connection for every facet of life. It’s interesting to retrace how that happened. I’ve recently been reading James Bridle’s book New Dark Age and Azeem Azhar’s Exponential, which touch on this territory in different ways. But to get back to your question, I suppose the first online image I would’ve seen is some pixelated (and likely unsavoury) JPG over a classmate’s shoulder on a Nokia phone. What was your first memory of this?

We were here but now its time to go, 2022, digital collage

That’s funny, I have the same memories of looking at poor images on Nokia, then Blackberry when I was 12 or something. The crazy part is that we shared these images mostly for backgrounds (cars, fake broken phones, very cliché naked women, etc.) but we were using bluetooth and not really the web to send those. I really started to discover the internet by myself with MMORPGs and blogs later.

But 15 years later, every year, there’s 1000 Billion images published online. Everything is duplicated and scanned in an endless process. As an artist working now with this material, I was wondering how you proceed to choose images that you work with.

That’s a good statistic, I might start using that! It’s kind of mind boggling isn’t it? I suppose it's easier for most of us not to think about it. I, however, think about it a lot!

My main approach to finding material is to constantly be open to coming across things, being curious and not limiting myself or imposing an ‘internal critic’ at the initial gathering stage. This gathering is a lifestyle and a way of being. It’s probably my favourite part of my practice. It’s started to extend out from just scavenging online, to always going into a charity shop when I pass one, and habitually taking photos of objects and textures in my daily life. The iPhone photography I just think of in the same way as downloading an online image made by another - the ease and simplicity of smartphone photography now feels so far removed from ‘proper’ Photography, that I just think of it as ‘stealing reality’. All of this material I think of equally, it enters a sort of hard drive soup that I can ladle out from when I come to make a work.

To go back to this phenomena of abundance culture - the too-muchness of everything that feels like it came to a head, for me at least, with the popular uptake of the smartphone in the early-2010’s - I often find myself coming back to the Greek myth of Sisyphus. There’s a futility of working against this never-ending tide of information and content. Competing with, or adopting the approach of a machine appeals to me, in these absurd attempts to be a human search engine or database. I’m most drawn to this detective-like investigation and study of sub-genres within sub-genres. By the end of each ‘investigation’, I might be digging down to the uploads that even the uploader had forgotten about. This stuff is buried at the lowest strata of what a search algorithm might suggest for you. This fascinates me, this concept of what we might call ‘digital waste’.

With the popular uptake of browser-accessible AI systems like Dall-E mini, I’m also thinking about how my practice relates to this and the future of images. It’s an interesting but quite scary moment. Perhaps machines will just start to make images that machines like, and leave humans to their own devices. What are your feelings about this seismic moment with AI?

Factory Reset, 2022. Installation view at SET Lewisham, London. Photo by Max Colson

I have this same feeling of a “turning point” in 2011. Everything started to accelerate, and in every field. In art, it was the beginning of contemporaryartdaily.com, or artviewer.org where exhibition views started to hold more currency and eventually become more stimulating than artworks themselves. It’s close to what the accelerate manifesto was discussing as well. And you’re right using the myth of Sisyphus, since we have the feeling of a revolution every year - AI and the easy access of Dall-E is a good example.

What’s the point of doing visual art now? I feel like the context matters more and more. We may use the same web, scroll the same feed, enjoy the same image, but artists have the power and the humility of choosing carefully what they want to work with and exhibit it in a very specific context, whereas machines can’t.

So how do you pick one specific image? Is it part of a feeling at one moment, or are you looking for very specific stuff, for example one object that you knew you needed to work with?

You’re right about the context being key, what you choose or omit when making and showing work. For me, I’d describe it as images singing out to me from the sea of monotony – an accidental blur, the seductive flatness of scanning, ominous flash photography, slap-dash handwriting, murky pixilation. I find a certain quality in images I come across, even the tiniest detail can intrigue me and spark a new work. Often it's the technical flaws of amateur photography that I gravitate towards. I’ve been collecting material in this way since 2015, so I’ve got quite a keen radar as to what I want, but its very much “I’ll know it when I see it”. Searching for something very specific tends not to work. I’m much more interested in letting my subconscious desires feed in, and letting happy accidents occur. That’s usually where the gold is–the marriage of, or slippage between, the intentions of a machinic algorithm, and the biases of my subconscious.

As search and suggestion algorithms become increasingly sophisticated and opaque, orchestrating these situations of happy accident and productive misinterpretation becomes more and more challenging. You can see this with the way YouTube has gone from this beautiful and strange video Wild West, to becoming a monetised streaming and advert-laden behemoth. But I think artists will always find a way to get around these barriers, and I’d say that this circumnavigation or mistreatment of algorithms and software–the endeavour to make room for intuition, aggression and urgency in the digital workspace–remains at the crux of how I try to operate. The introduction of real-life photography and analogue sources contributes to this and helps me evolve and introduce new elements of chance.

Factory Reset, 2022. Installation view at SET Lewisham, London. Photo by Max Colson

The process you’re using reminds me a lot of an Archaeologist. Even as a spectator, I think your work is a lot about digging into the unknown. We’re not expecting something and at the end we find what we were not looking for; a broken algorithm. I remember a video from a Youtuber called Vinesauce, visiting an online video game called Active Worlds (1995) that nobody plays anymore. It’s an open world and at the end the guy met the last player, walking alone in this field of ruins. These mixed feelings of anxiety, joy of discovery and nostalgia are very close to what I see in your work.

In your latest solo show, the hanging looks very similar to an open world as well - very immersive. The eyes are constantly caught by images, no matter where we look. Maybe you can tell me how you proceeded to build this particular hanging?

I like your description of this video game end of the world scenario. I’m very interested in those lost or dormant communities and the mark they’ve left on virtual space, or conversely, the mark that their digital experience has had on them. I find this particularly interesting in the wake of the COVID pandemic - what fundamental changes has this experience of isolated, slowed, screen-bound lifestyles had on us? During the lockdowns in the UK I was making work that was exploring this moment; the waves of anxiety and the flattening mundanity. I was thinking about how this extreme blurring of leisure and work, online and offline, screen and physical space, has changed us. I began thinking: how does technology haunt us? The solo show you’re referring to was a culmination of a lot of this work. I called the show Factory Reset, as at the time it was staged (summer 2022) it felt like this peculiar moment when we (the UK) were attempting this collective amnesia of the trauma of the past 2 years, like a device that is wiped clean and returned to its factory settings for a new ‘life’. But of course, as much as we may wish it away as some bad and very protracted dream, this experience is now with us all, like cache files that refuse to be deleted (to extend the analogy to its limits!).

So to answer your question about the way the show was curated, I wanted to imagine the gallery space in SET Lewisham (in South East London) as a kind of abstracted computer desktop. When you entered you were surrounded by images like an overcrowded computer background. The gallery became an interface populated by these dense and complex digital collages I’d made, as well as hundreds of the original images which make up my ever-growing archive of downloaded, scanned and photographed materials, which were printed as stickers and strewn across the walls. These works are about the feeling and affect–the bodily and psychological toll–that this smartphone-hyperconnected revolution we’re living through is having on us all. I never wanted this sense of abundance to leave the viewer.

There's always something disappointing about having an edge to the image, so I think this kind of immersion is key to the presentation of the work in physical spaces, and is something I intend to lean into more with my next exhibitions. But, like in a constructed game world, there is an economy of images, the use of negative space and an inherited ideal of beauty that I feel still permeates what I’m making. I suppose this underlying art historical reference and an intrinsic human sense of beauty is something that is present in both our practices.

Factory Reset, 2022. Installation view at SET Lewisham, London. Photo by Max Colson

The first time we spoke we were talking about how to move from the computer to a physical space. So I wanted to talk about “collage” with you. It’s the same word in French but I'm not sure if it has the same implications. I always use the word “assemblage” in my work because collage for me is a very physical join between two images, where we can see the gap and how one is added to another. You’re using a lot of fake shadows to trick the eyes. In the end it’s very difficult for someone not practising Photoshop to see what is really in front or behind, or even if the work is fake or not. What’s your relation to this idea?

I also have an uneasy feeling about using the word “collage”. It has a lot of baggage, and I feel like it doesn’t describe this new form of digital image making. It can put the wrong idea in people’s heads. Shall we invent a new word?

This idea of ‘real’ or ‘fake’ that you mention interests me, and goes back to the Trompe L’Oeil painting techniques, which in turn influenced how screens were made and how interfaces were designed. I find it interesting that software was often designed to mimic real world analogue processes - cut and paste is a good example - when we know it can do so much more. But I like to play with this element of the ‘handmade’ in digital production, and the absurdity of it. For instance the jagged edge that is left with Photoshop’s ‘magic wand’ tool - I like to keep hold of these moments of imprecision. For me it's important to have the traces of origin in a work, different fidelities tell you that images have had different beginnings, some may have travelled further (and therefore become more compressed and pixelated) to get where they are now. Recently I’ve been printing the digital collages as multiple layers on separate sheets, and then re-collaging them physically onto substrates like billboard poster paper, custom-built cardboard boxes, perspex or glass. This is particularly visible in Hyper Meatspace Blues (2022), which is combining digital painting, airbrush spray painting, physical collage and stickers. The inevitable mistakes and textures that come with techniques like papier mache serve to complicate this viewing experience. I’m interested in doubling the logic of something in this way, confusing the eye and making you question what you’re looking at. Where does the image begin and end? Where is the surface, or did it ever exist at all?

Hyper Meatspace Blues, 2022, digital collage print on Blueback paper, aerosol paint, stickers, 1189 x 1682mm. Installation view at SET Lewisham, London. Photo by Max Colson.

Hyper Meatspace Blues, 2022, digital collage print on Blueback paper, aerosol paint, stickers, 1189 x 1682mm. Installation view at SET Lewisham, London. Photo by Max Colson.-

duncanpoulton.com/

︎ @duncpoulton

gasparwillmann.com/

︎ @gasparwillmann

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Tal Regev.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED