Eddy Dreadnought & Wilson Firth

-

Published in April 2023

-

Eddy Dreadnought

Wilson Firth

-

We didn’t get to know each other at medical school, despite being in the same year. Our friendship started as trainee psychiatrists in Oxford 8 years later. Now after leaving long psychiatrist careers you’re a writer, I’m a visual artist.

The medical course started in the dissection rooms, six students per cadaver.

I wonder how we coped with confronting the human body in such a raw form. I was eighteen and sometimes try to imagine what effect 'the anatomy experience' had on us. As an entry into an elite? As an aesthetic? I remember all too clearly the Anatomy museum whose walls were lined with all the glass cases and jars that we had to pass through on the way to a kind of underworld, a portal into the strange unique intimacy of Medicine.

That study of anatomy has always leaked into my artwork. Also as a boy living next to an abattoir, retrieving footballs kicked over our garden wall from piles of oozing entrails was an everday experience, perhaps auguring the future. And my parents had a glass fronted bookcase full of repellent but fascinating medical textbooks.

It wasn’t only the Anatomy museum that was dominated by glass cases. As a child, my favourite exhibits in Kelvingrove Museum were vitrine-enclosed working engines of various types that came alive when you pressed a button; much of the ground floor was taken up with taxidermy in glass cases.

During my foundation course I began to display found objects in glazed boxes, inspired especially by Joseph Cornell’s ability to encapsulate ineffables. When I moved on to an art degree course boxing work was somehow regarded as too defensive.

Like using inverted commas. I can see that, but I remember a time when to enclose an object in a protective barrier was to confer upon it a degree of preciousness. People had little spare money back in the fifties and sixties so there was a whole culture of glass cases: every respectable household had precious items in a 'display case', full of things to be protected from the world but that politely requested your attention. Where has that culture gone? My guess is that nowadays it takes the form of the screens we spend so much time staring into, with their ever moving contents.

You’re right about the screens. A joke of yours that sticks in my mind: ‘I’ve had a good life, I’ve seen some great television programmes’. Funny and for me so true. Mediated observation is safe and protective. If the internet had existed in the 1960s I would have been a total vicarious recluse.

The implication is you might have reacted to that by being attracted to forms of art that directly engage with the physicality of raw matter. Yet both of us abandoned the physicality of general medicine or surgery to pursue careers in psychiatry. Like many jobs, psychiatry is difficult to talk about in any meaningful way to people who haven’t shared the experience.

The people I tried to help were endlessly gripping and occasionally terrifying. A few wait for me at the gates of hell. I miss attending to their stories, placing one’s own experience of coping with the uncontrolled at their service, the inspirational caring of most relatives. But not patrolling the social borders of psychopathology, being feared for the power of incarceration. Both good and bad experiences still elbow into my art work.

I think I blocked out my emotions more than you, so my conscious motivation was different. My worry about general medicine was that my future might be that of an adept technician, endlessly repeating the same procedures. I felt, perhaps naively, that the types of relationships you form in psychiatry might offer the possibility of mutual growth and creativity. In practice I think it promotes a certain degree of distancing, in other words it can create a barrier to engage in creative work thats personally confessional. The books and plays of doctor-writers such as Chekhov or Maugham are in many ways case histories in fictional form. They try to steer away from revealing too much about themselves, not realising that some sort of disclosure is unavoidable.

For me producing art was born out of psychiatric work. Walking the coastline hunting and gathering jetsam became a respite from the suffering in my clinics.

At art school found objects were crucial to my admission and ongoing work.

Did found objects make it possible to work with less obvious relation to ego? The acts of choosing and of creating a context, though, can't escape a degree of personal involvement.

To me their littoral nature was as important, the border between outside and inside is where I usually end up finding myself. An ideal position for many artists, to question something but to crave approval. My ego was front and centre in all this.

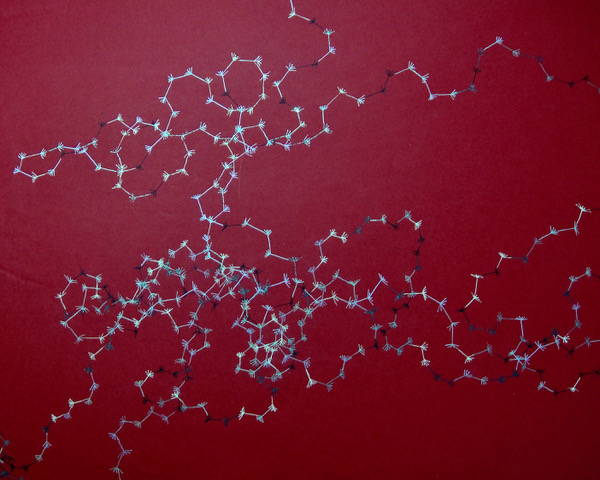

But you’re right about escaping personal involvement. On leaving psychiatry my plan was to make totally impersonal art. By then allergic to biography, I wanted no more responsibility or decisions for people in crisis. I delegated everything to chance in drawings where every mark was dictated by the throw of a dice.

With restorative time I moved into the narrativity of video, and to the amazement of those who knew my introversion, absurdist performance.

Is there a part of you that would like to convey something of psychiatry’s spirit, especially when at its non-judgemental best?

Predictably during my MA in Contemporary Fine Art Practice I gravitated towards Deleuze, Guattari and Artaud via ’Anti-Oedipus’. Luke Fowler’s film ‘All Divided Selves’ about R D Laing rekindled my early excitement about flattening hierarchies and keeping people out of hospital.

Subsequently I requisitioned treatment modalities: in an installation video ‘Anger Management for

Thunderstorms’, an abreaction of the river Don in Sheffield in another video ‘River Ritual’ with Paul Allender, a confessional lecture performance named for psychopathologist Frank Fish, and a video still in progress about the specialist furniture used in Psychiatric Intensive Care. So it never leaves you.

Maybe our job made us addicted to spaces where the unexpected seemed always to break free.

One of the reasons that people entered the space was that it allowed for a measure of unpredictability, but in the background there was, I think, always an agenda that had to do with reigning in what was unconventional and with making a case for the rules that constituted some form of imagined normality.I sometimes wondered about the nature of the unencountered entities that determined the boundaries of that space.

Getting to grips with art world anonymity I performed a lecture/manifesto for ‘Quiet Art’ (long before Hamja Ahsan’s 'Shy Radicals'). This proposed ‘art with the dignified quietism’ as Bataille wrote, ‘of a captain going down with his ship’. Art was:

‘Trapped in the embrace of contemporary culture and its history,

Always ideological,

Always in the service of, or reacting to, neo-liberal capitalism.

But also, I suspect, trapped inside more than that.

Something outside of politics, if anything can be.

Art is confined by the architecture of the human frame and senses.

By the twists and turns of the mind’s labyrinth.

By the myths and mores of social living.

Quiet art yearns to be outside even the imaginings of physics,

The anti-material, the forever rotations of symmetry,

The infinite regress of outsides, the shuffling of time.

Outside the void.

It should be a free zone,

Evading language, culture, history, science and all other ideology,

And any notion of transcendence’.

In terms of a purely personal response, this seems to me to express some of my problems about the idea of authorship when I’m reading or trying to write: the feelings of – who has the right to intrude on others, even imagined others, in this way? To some extent this can be restated as the - impossibility of being able to bear/yet to need - the sad reality of control.

These days my work relates more to loss of control. Getting older, addressing aspects of a void, dementia or death. My work is becoming increasingly abstract, inorganic and wordless.

An important poem for me is Larkin’s ‘the Winter Palace’ on losing memory:

‘… It will be worth it, if in the end/ I manage to blank out whatever it is that is doing the damage/Then there will be nothing I know/ My mind will fold into itself, like fields, like snow’. Increasingly yellow snow I imagine.

That poem brings up the idea of introspection which, I guess, informs a great deal of your writing and your art, particularly in your performance pieces.

Yes, alarmingly narcissistic introspection. Reaching an absurd apogee after the 2016 UK referendum and Trump election, and the shock of discovering people were not after all benevolently similar. My work retreated to the body as a refuge from all that. I performed ‘The Autonomous Regions of the Heart’ which ended in:

‘Let us hide in the quiet corners of the body

The periphery which carries on regardless

The purring engine rooms of check and balance

The parasympathetic dampeners

The sympathetic quickeners

The hormonal spa pools

The ganglions beaded in corn-rows

Burrowing blind to where thought is thought unknown

The autonomous regions of the heart

Where all is unconscious

And all is love’.

Suddenly this was ironically curtailed by the bodily betrayals of the pandemic.

Imprisoned in some unfolding science fiction, our bubbles burst, then burst some more. My artwork performed an emergency stop, but lockdowns at least provided time for an ungratifying review of where my work had been going. Too over explanatory, faux emancipatory, theoretical and self obsessed to carry on in that vein afterwards.

For me, an artwork falls apart as soon as I detect a conscious agenda, unless it manages to pull off the miraculous trick of transcending that agenda.

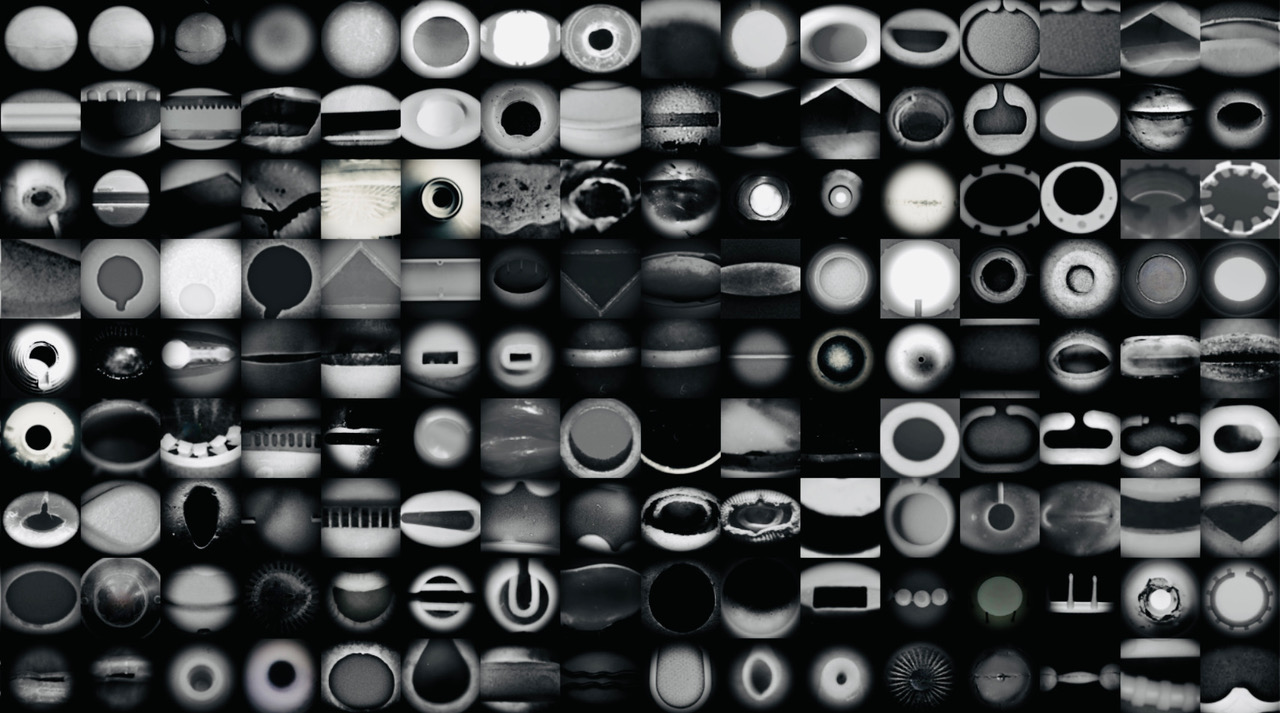

I know what you mean about conscious agendas. When collecting objects the more weathered, fractured and displaced the better. If it becomes clear what the identity or function of a found object is, their energy and mystery vanish along with this ambiguity. Too much case history has been given away, its confidentiality breached.

I regard these objects as ‘gifts from the ebb tide’ like Utamaro.

The classical concept of art arising from sources outside the self could be revisited, a source beyond control, beyond free will, beyond the senses, that appears at times of its own choosing.

Following lockdown I rediscovered Denis Donaghue’s reverberating phrase ‘the zealots of explanation’, James Elkins ‘Why Are Our Pictures Puzzles?’, was re-entranced by Deleuze’s poetic philosophy, his emphasis on becoming, rather than being or non-being, although now becoming is overshadowed by mutating viruses, war and ecological crisis.

And entertained the near-psychotic notions of Speculative Realism, as an antidote to our ruinous anthropocentrism. Where objects speaks for themselves. The art object’s quality as autonomous being, not merely explainable by its components, process of production, or relation to the viewer.

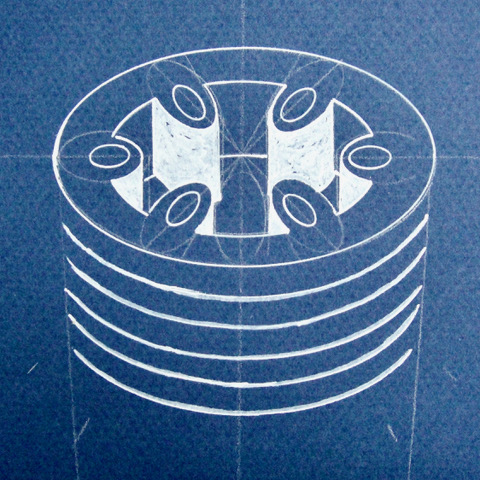

So now, if anything can be planned, I hope to continue collaborating with marginalised objects on producing silent abstract forms, as in the stills from a recent video screening above.

While waiting.

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Paul Chisholm.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED