Exodus Crooks

-

Interview by Jessica Taylor

-

Published in February 2024

-

After an incredible first showing in Brixton in London with ICF, with very moving and emotional responses from visitors, your solo exhibition Epiphany (Temporaire) is coming to your home city of Birmingham. Can you share some thoughts with us on the significance of sharing this beautiful and personal exhibition with Birmingham audiences?

I had mixed feelings when I first heard that the show would potentially be showing in Birmingham. There was an initial excitement and nervousness that I am sure many artists get when they are about to share their work. But alongside the excitement there were feelings of anxiety because the work is very vulnerable and refers to moments experienced in the city and regards people from my home city. And I suppose audiences in Birmingham are a lot different to audiences in London, so it will be interesting to engage with those visiting the show and hear their reflections on how they interpret the work and how they connect to it, specifically in a space such as Ikon Gallery. I also want to add that I think it is really quite special to exhibit in my home city because of what it means for the wider conversation around art in the UK, where there are assumptions that London is the only place where great exhibitions are shown. There is so much great art to be seen and enjoyed around the Midlands, as well as in London, and hopefully this show confirms that.

Epiphany (Temporaire), Installation View, Ikon Gallery (2024). Image courtesy Ikon. Photo by Rob Harris.

As I wrote that first question, I quickly revisited my use of the word ‘home’. I see Epiphany (Temporaire) as an exhibition that simultaneously questions the fixity or stability that some often associate with notions of ‘home’, while seeking an honest and introspective self-definition of belonging that is always in flow. Would you agree with this reading? And if so, I’d like to capture your feelings about ‘home’ as a concept in this particular moment - that may be a word, or a memory, or a quote - anything you’d like to share.

I would absolutely agree with that reading and for me home is something that is always in question. I am always reasoning with myself about what it means, where, when or who it is and possibly if it is a combination of all those things. To give a little insight into my upbringing, I moved house a total of 13 times while living in the Midlands, so my childhood and young adulthood were spent longing for somewhere to ‘settle’. The idea of settling is what I had been told I should aspire to, that it’s the normal thing seen in society, to aim for somewhere to permanently reside. But that wasn’t my experience, and I am not even sure if it is my desire now. I go back and forth on what I want and need in regard to this. Alongside all these moves, there was one place that always remained a stationary place of rest and comfort. That was my grandparents' home in Newtown, Birmingham. I have lived there twice in my life, and it is the only house where you can find traces of my upbringing. It is this home that sent me in search of another home - Jamaica. But to answer your question more concisely, my feelings about ‘home’ can be summed up in a sentence I wrote for another piece of artwork, a piece that I am yet to share but has been seen by the curator of Epiphany (Temporaire) and my friend Orphée Kashala, who very poignantly gave a different perspective and interpretation to the work.

The sentence reads: Home is only sweet because you get to go back to it.

When writing about your practice, you’ve expressed your interest in exploring the question of what it means to “return home or return to self”. Do you see a relationship between those two journeys, a relationship between the creative pursuit of a return to home and a return to self?

I do see a relationship between the two, yes. Mostly in a way where both the idea of returning home and the idea of returning to self run parallel to each other, as well as across each other. My journey of returning home and my journey of returning to self both happen using a creative methodology. I use art to interpret the world and process things I often struggle to process otherwise. It also helps me process these things with other people, engaging audiences in discussions around self and searching. The thing that continues to torment me is the idea that there is no answer or end to my question. This fuels my practice, but it also haunts me in a sense, because I think a lot about what home is but even more about how I come home or if I ever will. My early practice focused solely on returning home as a child of the British Caribbean diaspora, typically searching for a place for us to belong, but my journey is much more nuanced now in that my notion of self is posed as a version of home, and self has always been foreign to me. My relationship to myself was interrupted from a very young age by the introduction of religion, which at the time encouraged me to ‘give myself over to God’. I was told on many occasions that ‘I must die so that God can live within me’. I was taught that my life was not my own, and I have spent the last 6 years trying to explore the opposite idea.

Doing Duties for Miss Dell, 2023. Courtesy ICF and Ort Gallery.

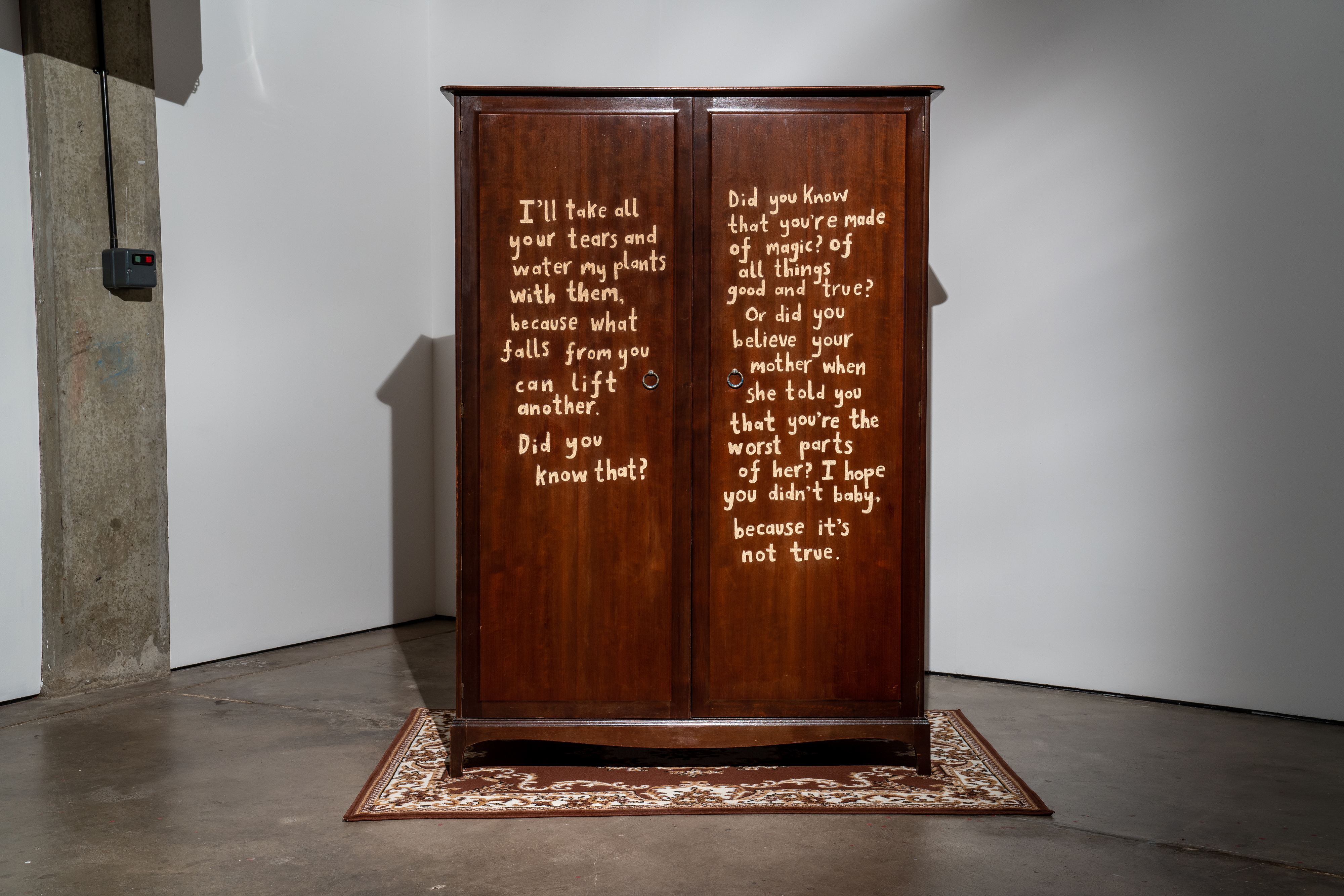

In Epiphany (Temporaire), several of the works you’ve created - particularly Doing Duties for Miss Dell and A message from my ancestors - directly allude to domestic spaces. You’ve taken the familiar forms of the wardrobe and the washing line and transformed them through the very delicate and yet labour-intensive processes of carving and stitching by hand.

How does your engagement with these objects offer us insight into your approach to process as both a creative and introspective act?

This is a great question, one which as I am thinking about it, forces me to look a little deeper into how and why I make. Sometimes I am not always so aware of the subconscious parts of me leaking into my work and so the vulnerability you see in my work is mostly intentional but, in some works, unintentional. I have a great affinity to both domestic and natural objects, including furniture, textiles, nature and living spaces, and this again stems from my grandparents' home. But I also know that there is a spiritual aspect to my practice that I don’t always speak much about, as I believe it is a powerful and sacred experience to be able to feel something instead of, or, in addition to having it explained. And so, in regard to your question, the delicate and labour-intensive production of domestic objects also entails a sacred element in that when they exist in a space, they transform the space and atmosphere. Orphée recently introduced me to the word ‘Nkisi’, a word used in the Congo, which loosely means an object imbued with sacred, spiritual energy. He described A message from my ancestors as Nkisi, which was both humbling and enlightening for me, as I never had a word to articulate some of the spiritually-charged objects I create, but I was searching for the word in English, which is always such a limiting language for me.

A message from my ancestors, 2022-2023. Courtesy ICF and Ort Gallery. Photo by Katarzyna Perlak.

A message from my ancestors, 2022-2023. Courtesy ICF and Ort Gallery. Photo by Katarzyna Perlak.The domestic spaces that you allude to will feel familiar to those who grew up in a Caribbean household, due to the symbolism and visual signals that you’ve embedded in the artworks. How does the Caribbean function in your work as a symbolic, reflective and generative space?

The Caribbean is a definitely a core part of my work as you have identified, and I use these symbols of the Caribbean as a code that only those who have feelings and experiences of displacement and diaspora are able to understand. There is something special that happens when somebody is able to recognise something in my work as a shared experience. That’s when I feel the work is active and fulfilling its purpose, when somebody else enters the space and has a nostalgic response to a piece. That emphasises one of the many powers of art, that it can transport you to previous lives, remind you of loved ones and moments of complexities, and can connect me with a stranger through our shared understanding and experience of a Caribbean culture, which is intimate and often complicated.

Epiphany (Temporaire) is the result of a very unique and special artist and curator relationship between you and the exhibition’s curator Orphée Kashala. How has the openness of that exchange influenced both the works in the show and your feelings about exhibition-making as a practice which can be shared, collaborative and intimate?

I feel really grateful to, not only have met Orphée, but also to work with him in this way on a proposal that he wrote a couple of years ago. I can’t emphasise enough just how special our working relationship is, in that it is very intuitive, soft and synchronised. Our rapport, our aims and our morals within our individual and collective practices align effortlessly, as do all of our decisions, and the way we make them are meticulous and slow. I could speak in length about how we work together but to answer your question, this collaboration has set a high standard for working and has encouraged me to embrace my vulnerable way of working when someone is willing to hold that space for me. My respect for Orphée’s vision and his respect for my practice means that we are in constant, gentle, yet deep dialogue about the possibilities of ideas, language and home. I also feel that the way we have worked together has developed our professional relationship with the industry as we have learned and talked a lot about ways of working, boundaries, culture and Western art institutions. I don’t want to talk too much on his behalf, but I can say, for me, this has been the most harmonious collaboration of my time as an artist so far.

I am incredibly inspired by the reflexivity and vulnerability that you pursued and expressed in the making of Epiphany (Temporaire). You grappled openly with questions on spirituality, identity, loss, shame, and the fleetingness of creative imagination. Why was it important for you to share that vulnerability with others?

Both shame and pride have been the foundation of my upbringing and have consumed a lot of my life, so it has been an act of quiet rebellion to be vulnerable in this way, to share the things that I felt shame for, and to tackle this idea of perfection and preserving image. I think in some way, as well, my longing for connection comes through in my work as I am trying to move closer to a place of empathy and exchange tenderness with my audiences. In some small ways I use art to offer a bit of myself and my experience, and in doing so engage in the intimate conversations and moments that come from that. This is something that happened a lot during the first iteration of Epiphany (Temporaire) at Block 336 in Brixton. I shared so many beautiful conversations with people about memory, shame, love, Caribbean culture and the matriarchy, that I feel a little less alone in these topics and hopefully they do too.

Y: the symbol of man, 2023. Courtesy ICF and Ort Gallery.

In the mixed media installation Y: the symbol of man and the film Leti’guh, the slingshot functions as an important allegory for the birth and death of ideas and provides a commentary on humanity. Can you speak more about the beautiful story behind these works?

In the film Leti’guh, you hear my mentor and friend Phillip Ambokele Henry very eloquently share his philosophy on the slingshot and what it represents, which led me to think about how it further represented the self. In stripping it back beyond its function as a slingshot, I became really interested in the ‘Y’ shape as a symbol, dare I say, akin to the cross. I am not attempting to make it as recognisable as the cross, but I am attempting to challenge the idea of symbolism through repetition and gendered perspectives. In staring at, living with and working with the ‘Y’ branches for some months, I wanted to dress the shapes in ways that expressed the many versions of myself that have existed in the past and exist simultaneously in the present too. What makes humanity beautiful is both our differences and our similarities, and so in Y: the symbol of man, I’d like to think I am presenting two schools of thoughts, firstly that our skeleton may be the same, but our expressions and stories are different, and difference doesn’t have to mean conflict or division. And secondly, that western ideas of masculinity are unimaginative and inhibited, but they don’t have to be.

Leti'guh (Film Still), 2022 -2023. Image courtesy Exodus Crooks.

We’ve spoken a lot about your use of wood in the previous questions. It feels important to acknowledge your personal and artistic embrace of natural materials, plants and gardening. Where did your love of plants stem from? And what do you think we can all learn from plants?

In Malidoma Patrice Somé’s book The Healing Wisdom of Africa, Somé belongs to a group of people called the Dagara who originate in what is now known as Ghana. The Dagara people believe in a hierarchy of consciousness, and I suppose I do too.

Somé writes “…the trees and plants, are most intelligent beings because they do not need words to communicate. They live closer to the meaning behind language… And where does meaning reside in its fullness? In nature.”

My proximity to nature began in my grandparent's home, which also happens to be my childhood home. There is a room, we call it the front room - which continues to confuse me as it is at the back of the house - and this room has always had this border of plants around it. They climbed the walls and consumed one particular corner near the window, and they always looked as if they were trying to go back outside. I have not really stopped to think about if this is really what encouraged my longing to be near plants but over the last 5 years, I have noticed that the more in tune I became spiritually and the more in touch with myself I became, the more I craved to be amongst nature, further pointing towards the philosophy of the Dagara people. More recently, I became a facilitator for Grand Union’s Growing Project, a community gardening programme, that works with organisations who support vulnerably housed people and those experiencing crisis. They work to increase access to green space without any obligation to be productive. And although it is a programme that centres the experience and needs of the vulnerably housed, it has definitely acted as a significant space for my own healing. Every week as we grow and harvest together, I feel the most at peace, inspired and grateful. My relationship with Jamaica only further enables this love for nature and even more so my love for and interest in working with natural materials.

I have to mention two inspirations for working with natural materials: my mentor and friend Marcia Henry, an artist from Portland, Jamaica who carves into calabashes, and her peer candidly known as the Bamboo King, who creates these beautifully extravagant furniture pieces solely from bamboo. I think there is a lot we can learn from plants, but I will just share the two lessons I remind myself regularly of: that we too have seasons and that our existence doesn’t have to be tied to our productivity, but rather it can just be about beauty and experience, just as it is with some flowers.

Epiphany (Temporaire), Installation View, Ikon Gallery (2024). Image courtesy Ikon. Photo by Rob Harris.

I now try to end all of my interviews with the same question, as an opening up rather than a closing down of the conversation. I fully recognise that an artist’s practice contains multitudes which no interview or even body of writing can fully capture. Therefore, I want to ask you, what is a question that you’ve never been asked that you wish someone would ask you about your work?

This is a really tender and thought-provoking question; I appreciate ending our interview this way. Although I’m sure I’ll think of something more profound post this being published, my immediate answer would have to be: what do I want from my practice?

I think this is something that is always assumed and never really asked. I wish someone would ask what I want my art to do, what I want from and for my art, and where I hope my art will live.

To answer that briefly, I don’t want the type of fame and success the art world dangles in front of artists today; the accolades and gallery representation. I have had many interactions with gallerists and curators who offer me tips and tricks on how to succeed in the art world and ‘climb the ladder’, but they never ask if this is actually what I want. I think somewhere along the way it has been assumed that we want the same thing from being an artist; I don’t. I don’t want for my work to be recognised as “Exodus’ work”. I don’t want my aesthetics tied to my ego in order to appeal to collectors or institutions. I want my work to live in the archives of its viewers as memories and moments that freed them, even just a little bit. I hope that ten years from now, somebody is having dinner with an old friend and they are talking about something completely unrelated to art, and they reference a piece of my work they saw in Birmingham or Brixton. I want them to recall seeing this old wardrobe with a poem engraved on it which reminded them that the family you’re given here on earth is not the only family you have. I want for my work to live beyond the walls of a gallery, for it be referenced in life and love, and written about in relation to spirituality, education and tradition. If my work influenced the human experience in the same way television and movies do, I would feel successful. I would feel excited not because people know my name but because they know that my art exists in “a universe of relations governed by Mauss’s archaic notion of the gift - in which individuals ‘know’ themselves by actually exchanging with others those objects by which they are ‘identified’… much of what is worth knowing is quite literally self- evident.” (bell hooks, Art on My Mind).

In other words, my art is there to be identified and exchanged with as we attempt to better understand ourselves.

-

Epiphany (Temporaire) is on show at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, between 09/02/24 - 21/04/24.

The exhibition was commissioned by The International Curators Forum and Ort Gallery, and was presented at Block 336 in 2023, as part of the ICF’s year long residency at Block 336.

For more information visit the Ikon Gallery website.

-

︎ @exoduscrooks

exoduscrooks.com

︎ @ikongallery

ikon-gallery.org

︎ @icf__

internationalcuratorsforum.org/

︎ @ortgallery

ortgallery.co.uk/

︎ @block336

block336.com/

-

If you like this why not read our interview with David Gardner.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED