Gwen Evans

-

Interview by Alice Wilde

-

Published in November 2024

-

So I like to start interviews by asking what three words describe your work? I think this is a nice way to introduce people who might not be familiar with your work and perhaps set the tone of the interview.

Greenish, anxious and ambiguous.

TRYST, William Hine Gallery, London (8 October - 9 November, 2024). Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Wenxuan Wang

The last time we worked together was for your 2023 exhibition CIPHER in HOME's Granada Foundation Galleries. It's been exciting to see how you've expanded this body of work, especially with some familiar subjects returning in your new paintings. How has CIPHER influenced your new work and what new ideas or approaches have you explored as part of your current exhibition TRYST?

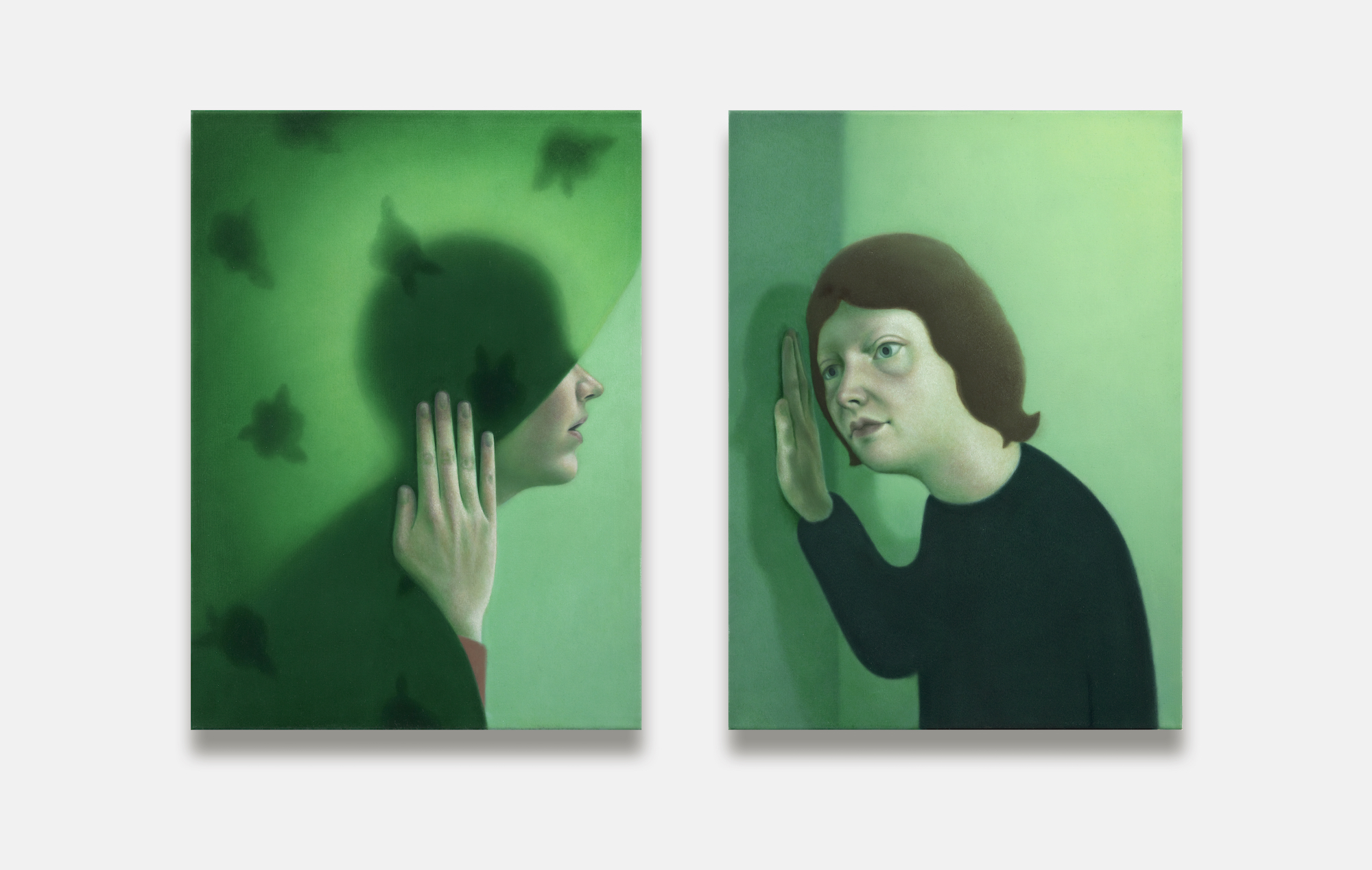

I see these recent paintings and drawings as a continuation and expansion of what was exhibited at HOME. Both bodies of work delve into themes around courtship, isolation and obsession whilst referencing nuptial portraiture. But I think the feeling of anxiety is pushed even further in this work to create a more sinister undertone with added elements of surveillance, with figures spying through frosted glass in Suitor, or peeping over suburban hedges in Meet Cute.

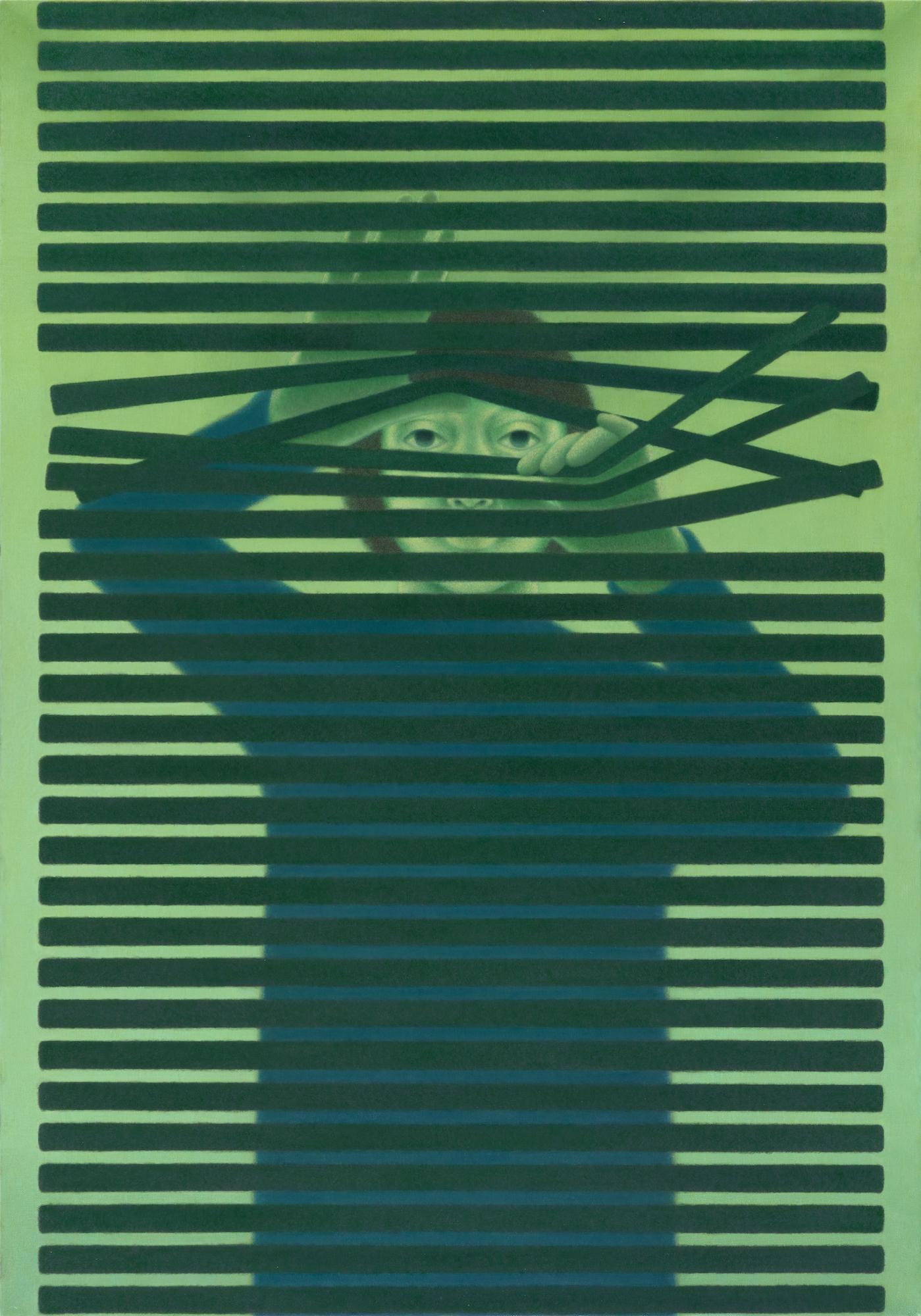

In The Watch the confines of the canvas doubles up as the edge of the window frame, with the figure peering at us beyond the picture plane, transforming the viewer to voyeur. Subjects have become more anonymised with faces obscured or turned away. But similar to previous work they’re isolated with physical barriers acting as conduits for themes around contemporary and social anxieties.

My previous work incorporated flowers, but this body of work looks more closely at how botanical symbolism has been used to signify courtship, love, and vice throughout the history of painting. There are also nods to Welsh culture in the work, with Welsh tapestry in Promise and Gift, whilst Impasse depicts a love spoon, historically offered as a gift during courtship in Wales. In addition to cultural, there are more contemporary references in the work, be that either in the spaces the figures occupy, or the imagery appropriated from film.

Meet Cute, oil on canvas, 2024, 100x70cm. Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Michael Pollard

Could you share which artists inspire you and how they influence or perhaps referenced in your own work?

I love the American painter George Tooker who was prominent in the 1950’s-1980’s. Associated with magic realism and surrealism, his work really conveys a sense of dread through isolation and surveillance that is striking. His use of ambiguous spaces to suggest a dreamed reality, and blending of facial features to anonymise figures are things I try and emulate in my own work. His Window series, The Subway and Government Bureau I like in particular, where figures are subjected to inescapable observation and claustrophobic isolation.

Another artist whose work I think of often is Lisa Yuskavage. I like how she uses colour to convey meaning, and the play between realistic elements and large abstracted areas of colour, almost similar to colour field painting. Like George Tooker her subjects are not individuals they are characters, often placed within dreamlike spaces, seemingly not always of their own volition or in control of their circumstances. Favorites of mine are Big Agnes, Big Little Laura and Changing.

Lastly Piero Della Francesca has been a key influence, especially his marriage diptych The Duke and Duchess of Urbino. The stoicism of the painting and contrast between the bronze skinned Federico and sickly coloured Battista Sforza is marked. Her pallor is said to reference her untimely death, which adds a real somber tone to what should otherwise be a painting celebrating a loving union. This greenish pallor is an element that is repeated throughout my work, which also ties in with ideas around the uncanny.

The Watch, oil on canvas, 2024, 100x70cm. Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Michael Pollard

I know that you are often inspired by early renaissance paintings, yet your work blends an inherently classical style with the Lynchian hint, whilst also capturing the isolation and distance felt in contemporary times. With this new exhibition, it feels you’ve really developed this sense of contemporary surveillance yet you can’t anchor the paintings to a specific period or moment, adding to the unease in your work. What is your process in terms of finding these uncanny moments ?

As you mention, figures inspired by renaissance painting are paired with contemporary clothing, enigmatic spaces and sometimes imagery from popular culture, like the roses from Blue Velvet. My intention is that this amalgamation creates a sense of ambiguity around time and place, which adds a feeling of the uncanny to the work. As Freud outlines in his essay The Uncanny, intellectual uncertainty is an essential factor in producing this feeling. The better oriented a person is to their environment the less likely they will get an uncanny feeling related to the objects and events within it. But he contradicts this by stating there must also be an element of familiarity for a feeling of the uncanny to arise, as it is a “class of frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar”. I try to create this feeling by suggesting domestic but liminal spaces that might seem familiar but cannot quite be placed. My ideas stem from scenarios I imagine unfolding in domestic spaces, many elements in the paintings like the frosted glass, Welsh tapestry, garden hedges are actually taken from my home.

Most of the figures have a greenish and almost sickly hue because of the verdaccio painting technique I use, but this also ties into ideas around the uncanny valley. This term first coined in the 70’s has close links to Freud’s theory around death and the uncanny. He states an eerie feeling can arise if we have doubts whether an inanimate object is in fact alive, for example dolls, waxworks and so on. I think the unnatural pallor of the skin, and depersonalisation if the figures can evoke this feeling, especially in Promise and Gift, where the lack of fingernails feels quite doll-like.

Some of my work appropriates imagery from the films of David Lynch, who utilises the uncanny through the idea of the double with doppelgangers and reflections. There’s a lot of mirroring between the figures in my work, which also extends to the spaces they inhabit in the home that can be read as a metaphorical “self”. Boundaries or thresholds are repeated in the form of doorways, windows or hedges, which gives the sense that these figures are “in-between”, with subjects uncertain and intentions unclear. I hope this feeling translates to the viewer and they’re left questioning if the paintings capture a blossoming love or something more sinister.

I wanted to heighten the anxiety in the work by isolating the figures even when together, whilst adding an element of inescapable surveillance or voyeurism, also a common theme in Lynch’s work. The idea of these figures covertly spying on one another, suggests something has gone awry, and that romantic tryst has morphed into obsession.

Gift, oil on canvas, 2024, 40x30cm. Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Michael Pollard

The tension in your work is so visceral, especially the juxtaposition of romantic motifs like the red roses with the darker undertones. I think one of the stand out pieces if I was to choose is the Meet Cute piece—it instantly brings to mind the opening scene of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. I also love the delicate depiction of hands in the exhibition. Do these symbols, like the flowers and hands, carry deeper meaning in your themes?

I realised how important the placement of hands were in the nuptial portraiture that inspired me, and they were becoming more central to my work, whilst playing an important role compositionally. I decided it would be interesting to do a series solely focused on hands, and I do think they feel more intimate, especially as the Welsh tapestry implies that the hands are resting on beds.

The flowers reference how botanical symbolism has been used to signify courtship, love, virtue and vice throughout the history of painting. I enjoy the duality that can sometimes arise from these multiple meanings. For example, roses symbolised passion or venereal love, but it could also signify the virtue of the holder by marking them as the bride of Christ as seen in Madonna and Child Enthroned with two Angels by Filippo Lippi. In my painting Promise, the carnation traditionally used to symbolise faith, love or marriage is juxtaposed by the hemlock in its sister painting Gift, a flower historically attributed to evil and death.

In classical painting myrtle is associated with Venus the goddess of love, but in my painting Suitor this love token, concealed behind frosted glass feels incongruous within the context of the painting. In Meet Cute a hand cuts a rose, either to present as a love token to the admirer or as a veiled threat, suggesting romantic apathy. Through presenting these conflicting and incongruous intentions I want to cultivate a sense of uncertainty and highlight the anxieties lurking beneath the surface.

TRYST, William Hine Gallery, London (8 October - 9 November, 2024). Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Wenxuan Wang

The subjects in your paintings are truly captivating and like I mentioned earlier you can definitely see how they connect to previous work whilst remaining distinct. I’m curious how you construct their identities. What is your process and where do you draw your inspiration from?

I start with little thumbnail sketches with various compositions. Once I’ve picked one, I’ll use family and friends as models and take images experimenting with the lighting and environment. I then simplify the image in photoshop and redraw it by hand, especially focusing on the figures to stylise and anonymise them. If I’m happy I’ll transfer it onto the canvas. So it’s quite a long-winded process really, but I’ve not found a quicker way to do it yet that I’m satisfied with.

Stylistically the figures draw on the early Italian renaissance artists such as Jacametto Veneziano. I especially like how young male subjects were depicted during this time-period as some of their features strike me as quite feminine, with the overall effect androgynous. I try to omit traces of individuality or gender in my own work as I like the ambiguity it creates. This also conflicts with the traditional heteronormative depiction of male and female in nuptial portraiture, but I like that it adds an element of confusion to the work. There might be one or two subjects that are loosely based on characters from mythology like Apollo and Daphne in Meet Cute, but I purposefully try and keep them indistinct. I think this allows the viewer to furnish what’s missing in the work, they construct their own idea around the identities of the figures and the intentions they have towards one another. I think this is much more interesting than presenting a closed idea of what the work is about.

Suitor, diptych, oil on canvas, 2024, 70x100cm. Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Michael Pollard

All of the paintings have been developed at Paradise Works Studios in Salford? I am wondering if you can maybe share a bit about the community at Paradise Works and how this has impacted your practice?

Yes, all the work has been made at Paradise Works. I first joined after graduating through a bursary, which provided a free space for a year and there were some fantastic painters around me at that time like Louise Giovanelli and Robin Megannity. Being able to pop into their studio to ask for advice or see what they were working on, definitely had a positive impact on my work.

At the moment there’s around thirty-seven artists based in the building working across various art disciplines, so there’s a real wealth and breadth of knowledge that can be shared. Their gallery space and programme also present the opportunity to exhibit or meet curators and artists from further afield, so it’s a great place to be.

Mute Point and Mute Point II, 2023, oil on canvas, 60 x 40 cm (each). Courtesy of the artist and William Hine. Photo: Michael Pollard.

-

Gwen Evans(b. 1996, Bodelwyddan, Wales) lives and works in Manchester. A graduate of Manchester School of Art (2018), her work was the subject of a solo institutional display, ‘Cipher’ at HOME, Manchester in 2023, following being awarded the Granada Foundation Gallery prize.

Selected exhibitions include: TRYST, William Hine, London [solo] (2024); More News About Flowers, Division of Labour, Manchester (2024); Manifestations, Pink, Manchester (2024); CIPHER, HOME, Manchester [solo] (2023); Bankley Exchanges, Bankley Gallery, Manchester (2023); Manchester Open, HOME, Manchester (2022); Open, The Royal Cambrian Academy, Conwy, Wales (2021); Talking Sense, Portico Library, Manchester (2020); Upside Down Bucket, OA Studios, Salford (2019); Twice As Nice, Ps Mirabel, Manchester (2018).

Alice Wilde is a Curator and Producer based at HOME in Manchester, working within the Artist Development Team. Alice is committed to supporting artists in the North-West, predominantly from underrepresented backgrounds, to develop their practice and she curates HOME's Granada Foundation Galleries. Through her work, Alice seeks to create an environment that encourages collaboration and care, whilst engaging with themes that connect to contemporary society and envision alternative futures. Alongside her work at HOME, Alice lectures at Liverpool John Moores University on the BA History of Art and Museum Studies Course, drawing on her own experience of curating, producing and working in the arts.

-

︎ @gwenevanswork

gwenevans.co.uk

︎ @alicemwilde

︎/alicemwilde

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Luke Routledge.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED