Linnea Skoglösa

-

Interview by Kollektiv Collective

-

Published in May 2025

-

Your practice exhibits such great command of working with space – the way you situate your work within a given context, the entire surrounding becomes part of your work in a scenographic, almost holistic way. Could you tell us about your approach to making a given space your own?

The architecture works with the objects, one informs the other. That’s why I get excited about making installations when I know the space in advance. I often work with mockups, mapping things out and imagining the space as a unified whole. There is definitely a scenographic quality to how I work, but I’m not building a set, I’m building a situation. A kind of spatial consciousness.

Decline FCN, 2025, ducati supersport subframe, faux leather fabric, Apple Mac Pro, office noticeboard 165 x 67,5 x 120 cm.

Each installation feels like a frozen moment: a strange living room, an empty bedroom. Like when you step into a holiday rental and can sense everything that has happened there, how many people have cried themselves to sleep in that bed, had sex, argued, laughed. The energy lingers in the walls. The room is still somehow loaded. Empty space carries memory, or at least, that is what I feel the moment I enter a hotel room.

Lately, my thinking around space has been shaped by ecofeminism and eco-theology, especially in how they approach ideas of decolonising space: rejecting ownership, resisting dominance and centering the peripheral. No one object leads. No single thing demands to be seen. They move together. I have noticed people often walk into a space and immediately try to figure out what is the main thing to be seen? Who is in charge? They want to read it, understand it, and assign value to it. And I prefer not to give them that.

Sunscreen and Hyperflesh (installation view) at Glasshouse at Gathering, London. Image courtesy of the gallery and the artist.

Sunscreen and Hyperflesh (installation view) at Glasshouse at Gathering, London. Image courtesy of the gallery and the artist.This very approach to space also allows you to work across artistic disciplines, from painting to sculpture to installation. Throughout your practice, you have co-developed its various components alongside each other, the sculptures inform the paintings and vice versa. Could you tell us about their relation to one another and how you approach such distinct, yet completely entwined visuals and methods?

I never approach a piece in isolation. They all live in relation; they all bleed into each other. Sculpture, painting, sound, video, they are all part of the same system. The materials inform each other, emotionally and formally. A brushstroke can hold the same weight as a welded joint or a flower folded into cloth.

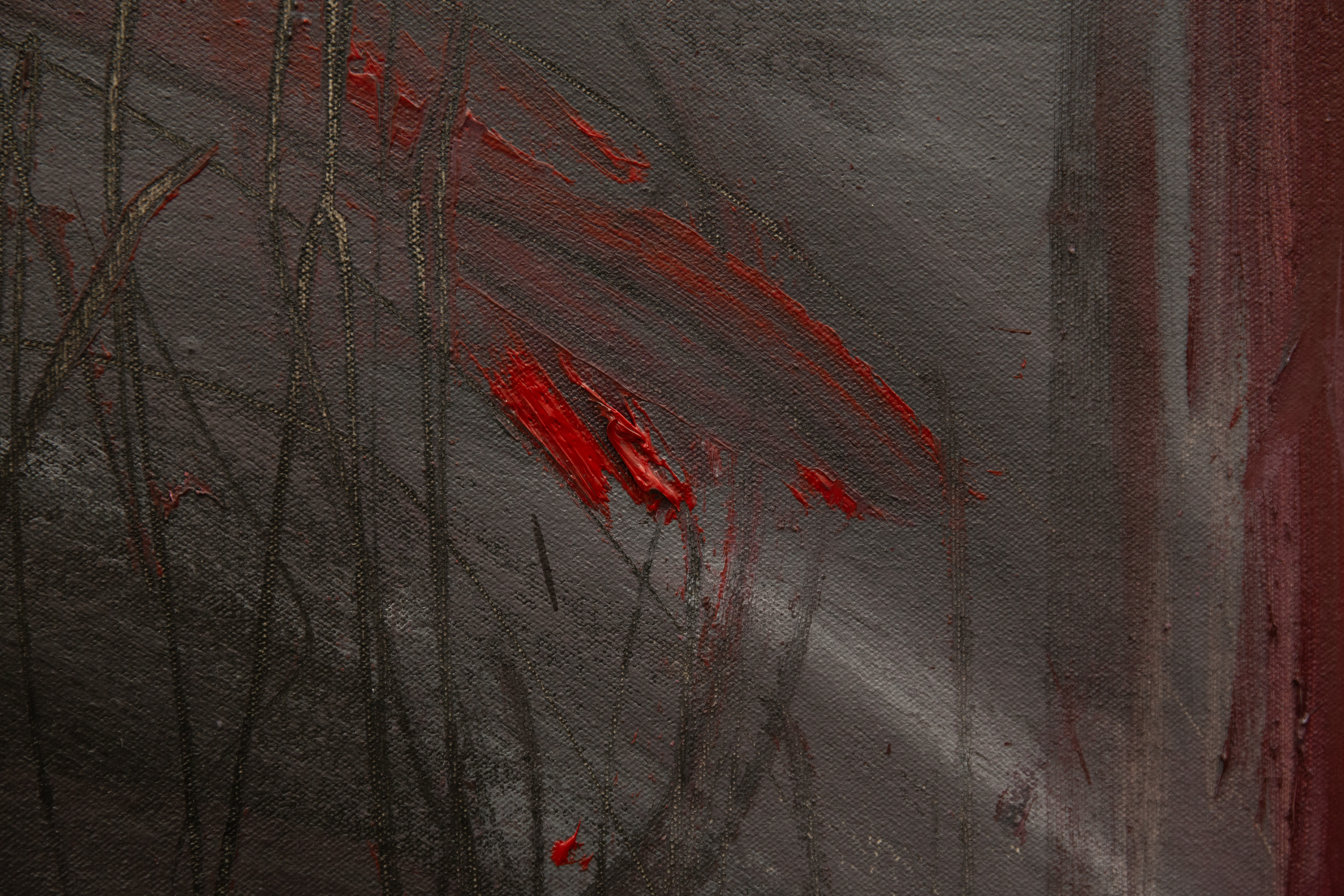

Violence in caring, 2025, oil on canvas, 210 x 140 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

Violence in caring, 2025, oil on canvas, 210 x 140 cm. Image courtesy of the artistIn the studio, I rarely work on one piece at a time. My process is expansive. I think in pairs, clusters, and constellations. Each work grows in relation to the others. A painting might reflect an internal space, while a sculpture holds the external body, or the reverse.

I often think of the paintings as inner landscapes or emotional backdrops for the sculptures – there is no primary or secondary work, but they are spatially different. Like how a sunset shifts the light on your skin. The paintings set the tone. The sculptures occupy space. Neither leads. They move together. Again, there is no need for hierarchy.

Violence in caring (detail), 2025, oil on canvas, 210 x 140 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

Your work is critical towards the way in which we confront the habits and conventions, desires and anxieties of the present day. There is an honest reflection on consumer culture here, acknowledging the way we embody it, how we draw from it and feed it, and simultaneously, the machinised disembodiment – part dystopian, part ridiculous – that underpins our consumer behaviour. Within that landscape, how do you navigate appreciation and aversion, complicity and revolt?

I see my practice as an extension of myself – of being a woman, objectified, socialised to perform, conditioned to obey. That embodied tension becomes my material.

I am also fascinated by ultra-stereotypes, 7-year-old beauty vloggers, "clean girlies," and the Selling Sunset cast. These figures are not merely cultural caricatures; they are symptoms of a system built entirely on extracting your currency as a means for safety, love and survival.

That is the contradiction: we are trapped inside what we resist. Consumer culture functions like a cult. Its deities are beauty, wellness, and optimisation, and we are trained to worship through self-surveillance and upgrades. The performance. The exhaustion. The fear of becoming ineligible. It is a collective fawning response disguised as a lifestyle to keep us occupied.

And that is where the work sits. I am not offering a solution, I do not believe that is the role of an artist. I am just holding up a mirror. There is something deeply human in that cycle, knowing something is wrong, and still doing it.

Downward Facing Dog, 2024, interceptor frame, waterproof car seat cover, swing arm rear, hair, aquarium, wooden frame. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sticking with the theme of conversations and dichotomies, we are taken by how your visual language is at once defined and fluid, there is the emotional and the structural, the futile and the functional. How do you navigate that space between normative markers, where contradictions creep in?

I often wonder what it means to share memories of yourself? Channelling them into a work, into an object? I often land into the contradiction that is language, I live there. I am not interested in fixing it or choosing sides. I want to stretch it, sit in it, let it stay uncomfortable.

My work is emotional, but also mechanical. It is fragile and absurd. That tension is the whole point. For me, painting is a tool, a way to meet myself. The work feels complete when a piece of myself has been transferred and sealed within it. It functions as a container, not the essence.

Exercism, 2024, marble, pilates reformer, hybrid travel pillow, ergonomic handles, steel, acrylic. Image courtesy of the artist.

Exercism, 2024, marble, pilates reformer, hybrid travel pillow, ergonomic handles, steel, acrylic. Image courtesy of the artist.The sculptures, often made from hard, industrial materials, carry a different kind of vulnerability, like bodies trying to pass as something else. They hold tension, pressure, and fragility all at once. At the same time, they carry symbolism, open to interpretation depending on the viewer’s subjectivity and their ability to recognise or relate to the material.

And I am drawn to that. Everything in the work is slipping between states. Nothing is settled. And I think that is an honest reflection of how life is. It is not a linear path, one singular way of being: we are constantly in flux.

Sweet Rupture, 2025, oil on canvas 230 x 180 cm, and Rupture and Bloom, 2025, ducati left frame cover, tripod, aquarium, 143 x 20 x 48 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sweet Rupture, 2025, oil on canvas 230 x 180 cm, and Rupture and Bloom, 2025, ducati left frame cover, tripod, aquarium, 143 x 20 x 48 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.The machine-like, industrial hardware in your sculptures acquire an almost animated / humanised presence, further disrupting standards and categories that inform contemporary context. In your mind, do the sculptures become characters / personalities with their own presence, narratives, emotional intelligence?

Without a spiritual component, I think the artist works at a disadvantage. When I’m in the middle of creating, I often notice what seem like coincidences happening more frequently than chance allows. An inner knowing that quietly shapes the work. Intuition allows me to trust that direction, without needing to fully understand it.

In a way, the sculptures become shells that carry a fragmented memory. They feel like users, entities with their own energetic charge. They never come from a sketch or a fixed plan. They purely arise from impulse, coming together like a kid would build with Lego, each part held in place by tension, each element locking naturally into the next, as a nervous system, connected into a new unity.

Bloom (detail), 2025, ducati left frame cover, tripod, aquarium, 143 x 20 x 48 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.

Bloom (detail), 2025, ducati left frame cover, tripod, aquarium, 143 x 20 x 48 cm. Image courtesy of the artist.They often take on hollow, almost human-like forms, suggesting a kind of disembodied experience. They look like they are floating, not quite connected to a skeleton, dissociating into the space around them. I think they speak to how I often feel in my own body, not tethered to my own flesh.

We admire how your work achieves to complexify the mundane, thereby capturing what many look past on the day-to-day. There is a lot to be said about the ordinary, the quotidian silence that pads our routines, the spaces we frequent, the mental queues we circle again and again. Can you elaborate on the presence and affect of the found objects – flowers, hardware, furniture – in your work?

I am drawn to the mundane because that is where the most pain and repetition hide. Our daily routines are full of attempts to regulate the body, to discipline the self. I think about what we ask objects to do for us, how we use them to soothe, conceal, perform, or signal success.

The vulnerability of living things, an exposed cycle: a flower that blooms, dries out, and dies. And yet, when a flower dies, we instinctively look for the conditions: the light, the care, the environment. We don’t blame the flower. We rarely offer that same care to our own minds and bodies. We don’t ask if the system was broken, or if the conditions were unlivable. In a capitalist structure built on performance and output, any pause feels like failure.

The same with furniture that starts out clean and desirable, but over time it wears down, loses its value. Electronics and hardware, especially, are designed to break or become obsolete. We treat them the same way we are taught to treat ourselves: to upgrade, replace and improve. That is what I’m interested in: how consumer culture links and shapes not just our surroundings, but our understanding of the self.

You recently started a new chapter when you became a student at the Royal Academy in London, one with a focus on research and developing your practice. Where do you see that journey take you?

Right now, I feel like I’m inside a cocoon. The pace is slower, deeper. I’m studying to find meaning, to dig into it, to stay close to what is real. In these times, staying honest feels radical, and that is what interests me most.

It is a chance to be more confessional in the work. I’ve always been searching for meaning, but now I feel more willing to name things I used to avoid. To sit with shame and repetition, not to fix them, just to let them be visible.

So, I don’t think I’m trying to “grow” in a professional sense. I think I am trying to be more truthful. That feels like enough.

-

Linnea Skoglösa is a Swedish artist based in London, working across painting and sculpture. Her practice moves through emotional tension and power structures, shaped by consumer culture and personal memory, with a heightened focus on disembodiment. Skoglösa's practice employs everyday objects such as wellness products, industrial hardware and screens, deconstructing and re-contextualising them to create new orders.

Kollektiv Collective is a nomadic curatorial project founded by Pia Zeitzen and Sasha Shevchenko, based in London and working internationally. Their practice spans exhibition making, publishing and collaborative research, rooted in decentralised structures and collective authorship. Engaging with a plurality of spaces, including cultural institutes, galleries and off-site locations, Kollektiv Collective approaches curating as a fluid, process-led act. Zeitzen and Shevchenko’s work explores the politics of space, labour and language, foregrounding multiplicity, friction and care to challenge dominant curatorial frameworks and reimagine how art can be encountered, discussed and lived.

-

linneaskoglosa.com/

︎ @linneaskoglosa

kollektivcollective.info/

︎ @kollektiv_collective

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Jun Rui Lo.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED