Oliver Braid

Interview by David McLeavy

Published October 2015

-

Oliver Braid's practice takes various methods of production therefore often resulting in an unpredictable outcome that often avoids any specific aesthetic trends. By having this approach, Braid aims to continuously ask questions with his work I order to avoid any level of artistic complacency.

-

Love Made Easy, 2011. Image Credit: Deniz Uster

My Five New Friends, 2012. Image Credit: Oliver Braid

Your work tends to evade common aesthetic trends that seem to sit around a lot of contemporary art at the moment. Is this something you consider or is it something that you tend not to think about?

I decided to become an artist at thirteen after my dad took me to see Sensation. From this perspective I grew up believing that artists each had a unique aesthetic developed through their individual philosophy. I didn’t ever identify this feature as possibly just a part of the aesthetic of advertising until very recently.

My mum is a primary school teacher and making a paper collage Facebook Zombie costume for a fancy dress party, when I was twenty three, was when I realised how comfortable I was with a playground/PVA language. It’s also something developed from being too scared to speak to men until I was about twenty three, setting me back in workshops for fear of technicians.

When I was studying for my Masters one of my tutors asked if I was aware of how unfashionable my work was, to which I would glibly respond that I’m not a fashion designer. More seriously I am developing a specific enquiry and correlating my production alongside this enquiry is what shapes the final work. If fashion was part of this investigation that would change things, but currently it isn’t. I’m making work on the basis that no-one else might care about it and therefore it really has to be worth doing and feel meaningful to me. ‘Contemporary Art’, like conceptual art or anything else is just a phase in history and I’m interested in expatriating myself to somewhere more solid. I’m making my own language which develops with each outcome, this just means it might take a while to translate.

For a very long time I didn’t fully understand how people found my ideas so ‘idiosyncratic’ (a popular response) but more recently as I’ve watched back interviews of myself I’m beginning to see. To a certain degree this is due to the discrepancy that arises between what I am serious about and what other people think I can possibly, really be serious about. For a long time I have been committed to extolling the negative impact of misunderstood irony on late twentieth culture and aiming to align myself with something more twenty first.

Given that all people are all different, never one thing or the other permanently, I have to say that I’m both conscious of my evasion and also naïve about it. I moved to Glasgow originally because I loved artists like Tatham/O’Sullivan, Beagles & Ramsay and Mick Peter – I hadn’t considered at all the more dominant aesthetic trends existent at the time. On the contrary Ellie used to tell me that when she first told people she was moving to Glasgow they expressed surprise and asked if she was going to start making minimal sculpture or grainy videos.

I don’t think being outside contemporary aesthetic trends has harmed my career in anyway. It just means I only work on things I really believe in and that I tend to get to work with curators and organisations that are really engaged with my work. It’s as if it’s so weird that you either ignore it or invest in it, and if you invest you do so wholeheartedly. I’m just making sure that investment is justified.

Ellie & Oliver Show, 2012. Image Credit: Edinburgh Art Festival

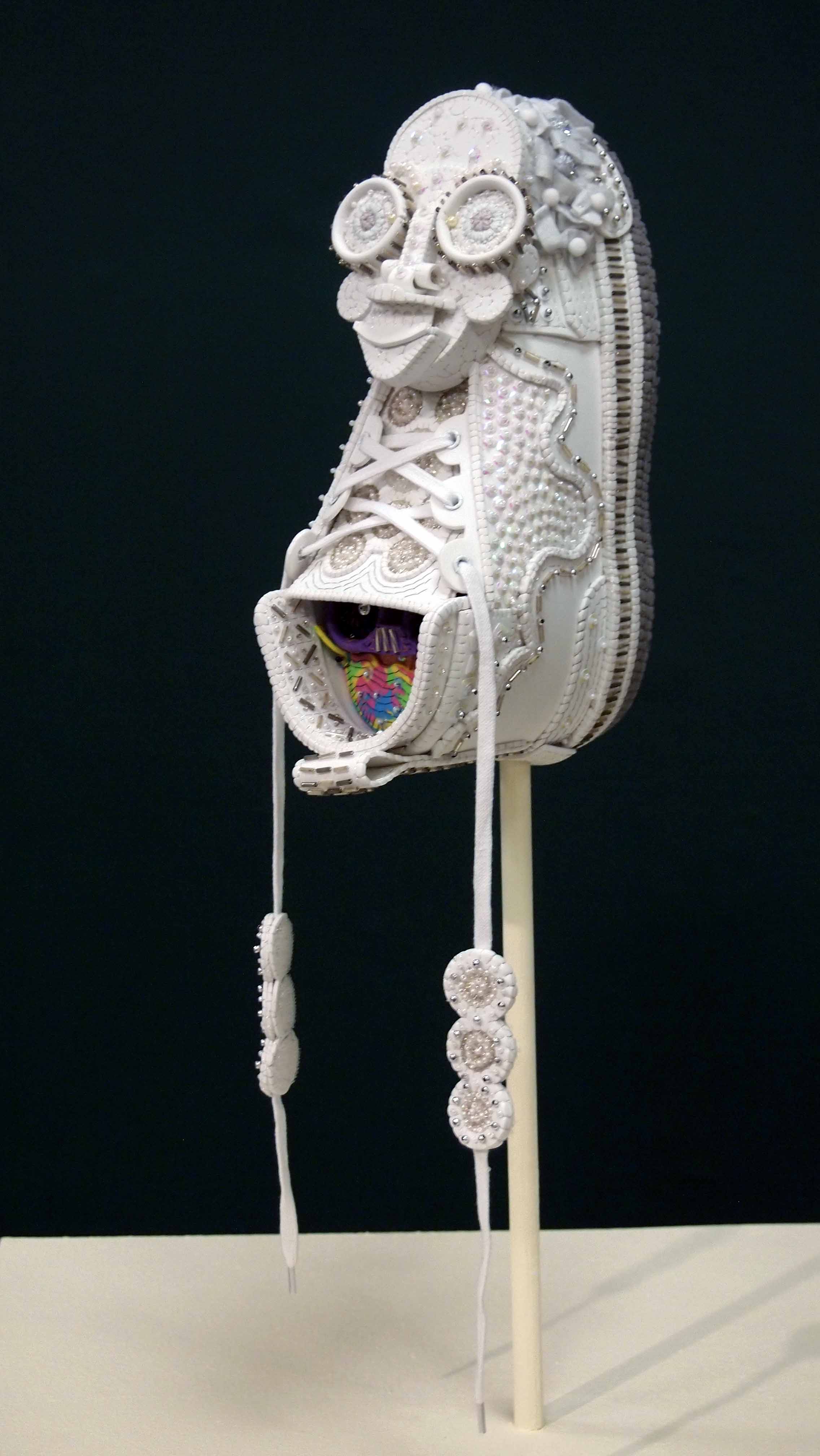

Sincerity Shoe, 2012. Image Credit: Oliver Braid

How do you measure what is justified? Is it measured by the level of interest shown in you by a curator/artist who you are working with or is it something else? Also, do you ever find yourself fetishising certain aesthetic sensibilities present in a lot of the work of your contemporaries?

I try to refrain from measuring justification myself. I’m not asking people to prove themselves to me, I’m just trying to provide enough information to warrant time spent with my work as rewarding. It’s me trying to justify – or sort-of reward – time invested. I like to provide for and encourage an Easter Egg mentality where things don’t need to be discovered in order to complete the game, but their discovery may enhance your awareness or the value you place on playing the game itself.

If people aren’t interested in taking charge of their own experience I’m not interested in chasing them. This feeling has been growing stronger for me over the last few years, but it’s always been there. I’ve worked in galleries and museums most of my life and I see how little time lots of people give to exhibits. There is a giant demographic of people who walk around exhibitions on their phones or with another person, talking the entire way round without even looking at the displays. Oh, they might stop once to Instagram an image of the exhibition to up their cultural status. My feeling is that these people don’t really need chasing.

This also means I rarely make proposals or applications now. I’m getting happier to wait and see who comes to me. People who come to you, without having to be coaxed, should always be better to work with and more supportive as they are coming with an established awareness. I feel so strongly about my work now that I’m not interested in begging people. For the last three years I have employed a ‘dignity rule’. This means I only ever try to interest the same person in my work three times and after that I never bother them again. I assume after three times that they will know my work enough to have made what they consider an informed decision. It doesn’t matter to me because I’m just going to carry on anyway.

For the record I have had some really brilliant experiences with galleries and curators but at the same time I refuse to be at anyone’s mercy. It’s bad for artists to forget that without them none of the structures and other ‘professionals’ would even exist. It’s so important because sometimes it seems that these structures and ‘professionals’ – and lots of artists - think it is the other way around. It’s heart-breaking to see the same artists’ time-and-time again up the arse of any curator that crosses the border into Scotland. I don’t understand why those people are so insistent on demonstrating what little confidence they have in the ability of their actual work. Being ‘pals’ with everyone is great but I think if people dislike you and still like your work that is better, more of a testament to what we’re actually supposed to be doing as artists.

I’m most interested in contributing to my field. I assume my contemporaries are interested in the same. I think if you really believe that art can ‘do’ something then this work has to be taken very seriously. A beginning point for this seriousness is the laying of solid foundations. Because I only decided to ‘become an artist’ at the age of thirteen I always felt a lack of natural foundation, the type exemplified by those filling sketchbooks since childhood. It took me a very long time to make anything on my undergraduate course because anything always felt phoney or derivative. Even now I only feel comfortable making something when I feel my reasoning is solid and that I can ‘own’ the manufacture more by understanding the material.

If I do ‘fetishize’ the aesthetic sensibilities of my contemporaries, which I understand as an obsessive fixation, it is often because I can’t understand how so many people come to the same aesthetic conclusions given the wide pool of potential research out there. For example – how did so many people all suddenly arrive at crudely hand-built ceramics? I become interested in those mass arrivals because I wonder where they came from. In the case of ceramics I could conjecture that the interest arose from a secret lust for the self, camouflaged onto an object which can accommodate anecdotal manufacture. But of course I’m also always suspicious of anything that appears to have arisen from the realm of ‘the they’. From this angle these blobby ceramics are as ubiquitous and rage-inspiring as men with top knots. If this is the real explanation for the wave of crude ceramics, the demand and approval of ‘the they’, then why do we need artists at all – mass opinion already won out. I really want foundations otherwise all this working is as illusory as a physics given without metaphysics.

I started this by saying I wasn’t the one measuring justification but I think I should flag up the judgemental tone of the previous paragraph before anyone else can. I do have a history of meting out my own judgements. Even as an undergraduate I took over the studios of two other students (so that I could have an entire room to myself) when I deemed them as not coming in enough. This was one in a series of situations where I have acted on a judgment only to discover how much it would antagonise others. In recent years these judgements came out more directly in my studio work with projects like I’ll Look Forward To It or Communal Dolphin Snouting. This behaviour stems from a sense of vocation to ‘contribute to my field’ and discover what art can ‘do’, often this involves taking sides and doing battle. It’s quite a medieval mind-set inspired by figures like Joan of Arc or Margaret Beaufort, only without God or Self to drive the mission. These two figures are also good examples because besides being very driven they were probably both quite annoying.

Snorlax Beanbag, 2013. Image Credit: Joey Villemont

Communal Dolphin Snouting, 2013. Image Credit: Andrew McCue

It’s very refreshing to hear someone who presents themselves in the way that you do, especially in relation to your confidence in your work and of the role that the artist ‘should’ play. I am interested to hear more about your exhibition titled Snorlax Beanbag, especially your decision to deliberately prevent people having access to interpretative materials, instead choosing to position as the invigilator. Can you explain a little more about the exhibition.

Confidence isn’t quite the right word or perhaps we just need to be specific about the type of confidence. It’s more closely a concrete awareness of the intrinsic benefit of my working practice. It’s beneficial to me so I have ‘confidence’ in my work the same way someone might in their family or friends. Or at least my brain has rationalised it to appear beneficial. So if I have confidence it is because my brain weighs up what I do in the world alongside how what I do effects my experience of the world, creating a synthesis that gives the two combined a value to me. The thing I’ve always had a harder time with understanding is if when I exhibit work I pervert this intrinsic value into something instrumental. Instrumental value seems like an attempt to enhance experience by stepping outside of or thinking ahead of experience. For me this kills any possibility of discovering what the work might ‘do’ by pre-empting it. Exhibiting also appears to imply I’d rather people watched me rather than ‘do their own thing’ and this goes against a perspective I’ve been working from since mid-2012 called The Certainty of Insignificance.

The Certainty of Insignificance is a kind of pro-hedonic perversion of Pascal’s Wager designed to remind me that it is much more likely that my actions in the world will be insignificant, rather than significant. For me this isn’t a defeatist attitude but one which allows me to explore without worrying if anyone else pays attention. When people express interest in what in what I’m doing that is (sometimes) nice but ultimately I don’t want it to have any real effect on the continuation of my work. When I first started my Master’s degree another artist in my year, but about ten years older than me, told me that everything she had ever got was through nepotism and I just think that is the real defeatist attitude. She is probably what a lot of people would think of as successful now – but what success is it to know that any interest your work garnered has nothing to do with the work and is purely through your relentless soliciting.

I’ve always tried to give the wrong impression of myself, a bad impression to see if people can gauge my work independently. When I first got to Glasgow I observed how so many artists performed seriousness as a way to entice people to take their work seriously, this made me want to perform frivolity. More recently I wanted to isolate myself and be unpopular as a person to see how that affects things. I’m also now very interested in the role of bitterness. Last year when I got fired from Many Studios one of the directors told me that if I didn’t stop working against things and undertaking this line of enquiry I would end up ‘a bitter old man’. Straight after that feedback I read Whistler’s ‘Gentle Art of Making Enemies’ and reflected on how the writing in that text did come across as quite bitter, but was correct none-the-less. I don’t know if I can really end up bitter if I just stick to the path indicated by The Certainty of Insignificance. It is more that the director who foretold my fate only sees from a perspective opposite to The Certainty of Insignificance where bitterness is possible, which is the position I know as, ‘The Need to Be Right’.

Despite all of this background information when you look at my work I think you should probably try to forget it all – I think this disappearing act is the role the artist might play most interestingly. Contributing to the field of art doesn’t have much to do with strategically producing work that you know will ‘work’ because it’s been seen before, it’s not about feathering one’s own nest or being more important than the work. I know for a long time it’s been cringe inducing and deeply unfashionable to speak of artists having a special role but we’ve already covered my response to fashion and I usually find embarrassment pretty unifying anyway. It’s not that I see artists as having a special role, but rather that a special role is played by anyone who goes all out at any expense in order to make the contribution that makes their effort worthwhile or appear to give meaning to their lives; this definitely includes martyrdom – the sacrifice of self to a cause; starving, stealing, selling your body, whatever it takes to bring whatever it is in to being. The artist should aim to ensure it is solely the art that is taken into consideration, rather than the maker. This might seem like a strange thing to say given my work but I think it raises interesting questions about how to judge autobiographically generated work. I’m still working out how to properly express this but using something like the ex-genesis Ad Hominem fallacy I think we can extrapolate to strengthen the point – art cannot be judged on the basis of its maker. Going back to our ‘artist-as-nepotist’ whenever I’ve expressed surprise at people’s interest in her work they tell me ‘she’s just such a nice person’, but what does that have to do with the quality of her work? When people criticize me, call me a sociopath etcetera, they seem to think this might impact on the quality of my work. These people are left with the ridiculous option that good art comes from good people and that is just not true. And likewise there is no guarantee that bad people make bad things – Fred West being a murderer didn’t make him a cowboy builder.

I think it’s probably different depending on what you hope to be. If you want to be a ‘contemporary artist’ then being a nice, good person is important to grease people up, but if you want to be an artist then what you are is irrelevant compared to what your work is. My basic feeling is that if you isolate yourself from anyway for people to access your thinking, make people think you’re a horrible person and then they still want you to work you’re a little bit closer to drawing the distinction between art and artist. Whether we like it or not there will come a time when all artists are separated from their work. The artist dies and the work has to stand alone for the rest of its existence. This is a comfort to us all, to know there is only so far that an artist can control their work and tell people what it does. The future people will bring their own evaluation which disregards how well or not an artist may have networked their art into circulation when they were alive. Obviously we see this all the time, we hardly need examples, but consider the posthumous revaluation of Blake. The even greater comfort is that is that eventually there may come a time where no traces of humanity will exist, or even if artefacts persist there will be no-one to see them, rank them, curate them and none of it will have mattered either way. We will be free, unaccountable, insignificant and there will be no-one there to provide interpretation. Obviously if something like Meillassoux’s virtual god came into existence and resurrected us all this might be trickier, but at least the ultimate should be able to give us a just and definitive assessment of artistic value.

On that thought it’s quite perfect that you enquired of Snorlax Beanbag. Prior to this work I always gave a lot of personal and interpretational texts to support my exhibitions. Snorlax Beanbag was the first exhibition made after discovering The Certainty of Insignificance, it came from wanting to internalise my locus of self-evaluation and pre-empting our potential future of lost interpretation. I wanted to see if people were uncomfortable with the lack of interpretative materials provided or see what that lack might do. The display design for this exhibition was made up of works hidden behind Snorlax belly shaped screens and the final belly hid me. This presentation of the artist hiding in the space was marked on the list of works as ‘Playing the Flute’. In Pokemon that action will wake a sleeping Snorlax and allow you to pass onto new levels. I was basically the sole source of interpretation for the exhibition but I wouldn’t approach anyone unless they asked me to explain something. The exhibition was reviewed quite badly; the reviewer complained that ‘despite the playful title’ the exhibition was ‘almost anti-social’. The reviewer also bemoaned the lack of interpretative material, whilst simultaneously noting my presence in the space. For me the review quite accurately described my work and my intentions meaning that the work ‘worked’. The poor rating given by the reviewer seemed to be based more on his personal opinion of what he expected the work should have been – which seems more like wishing for something you don’t have, rather than accepting what you do.

The One, 2014. Image Credit: Alan Dimmick

The Certainty of Insignificance, 2014. Image Credit: Matthew de Kersaint Giraudeau

It’s interesting to think about the distinction between the artwork and the artist. How does your participation in this interview fit within that idea?

So of course doing this interview might seem contradictory to me extolling the virtue of separating the artist from the art, but I don’t know if it has to be. In the interview format I’m giving my thoughts and sometimes I’m giving my thinking about the work. At the same time I’m asking people to disregard this when they look at the work and it’s this that might seem impossible to some. How can you forget after you’ve already read it? It seems we’re in a similar situation to what Susan Sontag would have thought about camp – to talk about it is to betray it. But at the same time surely no-one thinks that what I think is equivalent to what the work is, since when did words or thoughts accurately describe realities.

There’s a way I which for me the idea of ‘understanding the artwork’ has a parallel to the way one might try to understand one’s own personality, by making a synthesis of how you think you come across and how other people make you feel you’ve come across. But the problem with that is that I might have access to my understanding of how I think I came across, but I never have full access to how other people understand how I’ve come across, and vice-versa. The things I’m aware of are things like images, texts, ideas and that I have the ability to embroider these things into something new. But I don’t have a full awareness of how my ideas translated into this new thing in front of me. If I’m already at that remove then I don’t know how anyone else can get any further, or why they’d want to. ‘Understanding other people’ isn’t really what we do that much at all, ‘understanding the world around us’ isn’t something we do that much either. We try to, but beyond the very basic threading together of space and time and things that appear within those regions we don’t actually ‘understand’ everything we come across, we don’t have any concrete understanding of totality on any level. I think that’s an alright thing that I can live with and would rather actively promote how having to understand everything is an unrealistic goal when that means having the ability to have full access to something. When I have an experience of something my first engagement with it is intuitive and emotional, not excavational.

The intertwining of artist and art begins early in your education as an artist I think; you might watch inspirational films or something that inspires you to ‘become an artist’ before you really know what you are as an artist or what being an artist might mean. As you go through school, or at least in my experience, you are taught to build artwork as a rebus – a dream which can be decoded. People want to look at symbols they can decode in order to get an understanding. I think this is because the dream as rebus is so tied up to Freud and how much he effected our last century. Because of psychology and psychoanalysis we attempt to employ decoding not only in artwork but in general life too, second-guessing people’s intentions through their body language for example. Pop-psychology meant that constantly we’re both looking and analysing in a way where small parts seem to give meaning to a whole. This is fruitless as an exercise if there is no chance at perceiving wholes in the first place. People seem to think of the artist as a special part within this whole, one that can provide the key to ‘understanding’, but this is an archaeological mentality of always ‘reading backwards’. I’m interested in developing ideas that could come under the category of ‘reading forwards’, ways of understanding what the work does without that ‘doing’ having to come from an analysis-style uncovering. One example I have so far is the use of the sigil in chaos magic, a wish-magic practise involving the production of an image that is subsequently destroyed from consciousness. The passing into the subconscious of the image is what makes the image perform its work. In this version of making any attempt to remember or interpret the image would retard the process or may even make it dangerous (the latter point being purely personal speculation).

These kind of reasons are why I want to promote that people not only disregard understanding me as being part of the work, but also that they disregard ‘understanding’ (as ‘reading backwards’) entirely. This doesn’t mean however that we can’t say that we like an artist’s work and I guess that we use the artist’s name as a way to identify future works by that artist – although how we might both ‘follow’ an artist and experience new works whilst disregarding the tendency to line them up with previous works by that artist is quite tricky. I appreciate that it’s useful to be able to catalogue in the way we’re used to and shaking that off for a totally new and uncertain way of navigating the world at this stage seems impossible to imagine. My own personal example of using cataloguing to follow an artist would be how all summer I’ve been looking forward to watching the latest Quentin Dupieux film. I’ve just been on an eight-week install and all this time I’ve known that by the time that finished his new film would be available online. But he is also a good example because although he has a similar style which reminds us of his presence as director I don’t watch his films with any ability or attempt to reference them or ‘understand’ them through ‘reading backwards’. I finally watched the new film last night and was thinking how futuristic he is and how his style of film-making matches my (as-yet-undefined) vision for ‘reading forwards’. Dreams and nightmares crop up a lot in this film and one reviewer described the film itself as a series of dreams but what makes it special in this case, for me, is that they seem to be immanent dreams; dreams where everything that is is already deployed, where nothing is held in reserve to be uncovered or interpreted. The experience is the only experience.

Basically right now I’m interested in idiosyncratic or speculative production in the world that I don’t need to understand or excavate because I want to live in a world where it’s okay for things not to be totally dissected in an invasive and futile attempt to make ‘understandable’. A lot of people have been asking me to describe what they are looking at when they look at my new installation and so I just give them a very literal visual description of the work ,like ‘it’s a large structure, covered in a woven flesh coloured foam’ etc. I don’t think people can fairly expect both the death of the author and simultaneously to perform a sort of séance for the ghost to come back and give them a mini-tour. My journey was of great interest to me and I want yours to be of great interest for you, but I’m not going to show you my way when everything you need to find your own way is already there.

The one where we wonder what Friends did, 2015. Image Credit: Gillian Hayes

The one where we wonder what Friends did, 2015. Image Credit: Gillian Hayes

-

Oliver Braid (b.1984, Birmingham, UK) is an acquired taste living and working in Phew, an island off the coast of Glasgow. He has presented solo exhibitions and projects throughout the UK, these include: I’ll Look Forward To It, Collective, Edinburgh, part of New Work Scotland (2011), My Five New Friends, The Royal Standard, Liverpool (2012), Snorlax Beanbag, Intermedia Gallery, CCA Glasgow (2013) and Communal Dolphin Snouting , Transmission, Glasgow for Book Week Scotland (2013). In 2013, he undertook a 4-month residency at Triangle France, Marseille sponsored by Patricia Fleming Projects, Glasgow City Council International Office and Creative Scotland and in 2014 was awarded a Creative Scotland Artist Bursary. He collaborates with artist Ellie Harrison to present the Ellie & Oliver Show, a radio project which has been presented through CultureLab Radio, Newcastle (2012), the Edinburgh Art Festival (2012), Glasgay (2012) and Glasgow Open House (2014). Oliver holds a BA Fine Art from Falmouth College of Arts and MFA from Glasgow School of Art.

In 2015 he was in artist-in-residence at the Cooper Gallery, Dundee, presented his new solo exhibition, The one where we wonder what Friends did at WASPS Hanson Street, Glasgow and launched his first seasonal event venue Phew.

www.oliverbraid.com / www.phew.gives

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Kelly Best

-

© 2013 - 2018 YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED