Parham Ghalamdar

Interview by Yasmine Rix

-

Published in July 2020

-

Parham Ghalamdar structures his practice around principled philosophies displayed through sets of paradoxes. Observing traditional painting, he brings together both material and symbolic contradictions to address absurdity and its ties to political states of being.

-

Parham Ghalamdar: Solo exhibition, installation view, Workplace Foundation, Gateshead, 2020

Parham Ghalamdar: Solo exhibition, installation view, Workplace Foundation, Gateshead, 2020I know you have previously described your practice as a paradoxical love between realism and fiction - I feel as though you have produced a novel dimension to painting that captures absurdity in a time when absurdity is actually becoming more normalized. Do you feel the same or do you feel like things are strangely making more sense in the world?

Your question reminded me of Mark Twain's quote: "Truth is stranger than fiction...". There is definitely a resilient absurdist agenda to my practice manifested through a simultaneous juxtaposition of love and hate relationships. And yes, the situation that was previously the “normality” is becoming disrupted by a deeper absurdity, which is probably going to be the new "normality". However I don't resign to it, in every painting I try to protest the absurdity by taking it to extreme, as if the painter is the Greek mythical character Sisyphus, and the act of painting is rolling the rock to the top of the mountain; it's a constant cycle of failing and succeeding. I protest absurdity because Goya once said ‘the absence of reason produces monsters’.

It's also important to mention that this paradox is deeply rooted in my life: I'm a highly pro-western person who was born and raised in a highly anti-western country. I just recently had a solo show at Workplace Foundation and the day after the preview I was working in the kitchen of a pizza shop, with minimum wage. My grandma was German, my dad was raised in Germany and my dad used to celebrate Christmas with German Christmas songs while living in a highly Islamofascist state of Islamic Republic of Iran. It’s an endless list.

Yes I can say I agree and feel similarly about living in amongst paradoxes but perhaps not as extreme and interesting as your experience. As a result, you have created some very curious visual identities in your work which appear to be a combination of several different styles and historical approaches from Hieronymus Bosch to Dali. Would you say you draw from the western socialist realism canon?

You're right, we all have these type of paradoxical relationships with ourselves, our families, our communities, our schools, the nation and the world. It’s just happening on an extreme level for me.

I’m heavily invested in the train of traditions and histories of Western painting; I have drawn influence from Caravaggio, Goya, and Bouguereau to more contemporary artists such as the New Leipzig School. I strongly believe painting is a completely Western/European practice. For instance Persian Miniature, which is mistakenly referred to as “painting”, is purely illustrative because it’s simply not embodied and lacks the criticality of the each brush stroke made in painting; Persian Miniature is basically illustrated just like the Biblical illustrations.

Just to go back to the Bosch reference briefly, I am fascinated with his paintings because the sense of perspective and the subjects are very close to Persian Miniature examples therefore Iranians find it easily relatable.

I think we have an archeological approach to learning painting within the academy today. Learning and teaching painting has become more about conception rather than perception, which is beautifully, rendered in Merleau-Ponty’s essay “Cezanne’s doubt”. As a result, if one wants to rely on the history of painting then one has to dig deep into the histories and traditions of painting alone, it feels like there is little no training on painting in the academy especially within fine art courses.

By academy, I am referring to art schools and by art made collectively, I mean art made based on collective agreements rather than arbitrary cynical emotional preferences. If we want things to function then we should avoid fictional solutions. Painting is first and foremost about perceiving because that’s the way one interacts with the painting. To make sure the eye and mind engage with what is perceived, the painting must be organized and reasonable decisions have to be made. That’s why one should study the traditions and histories of painting, to rely on such treasures to make informed decisions. It is as if the act of painting is a way of putting the world back into order, bit by bit, one painting at a time.

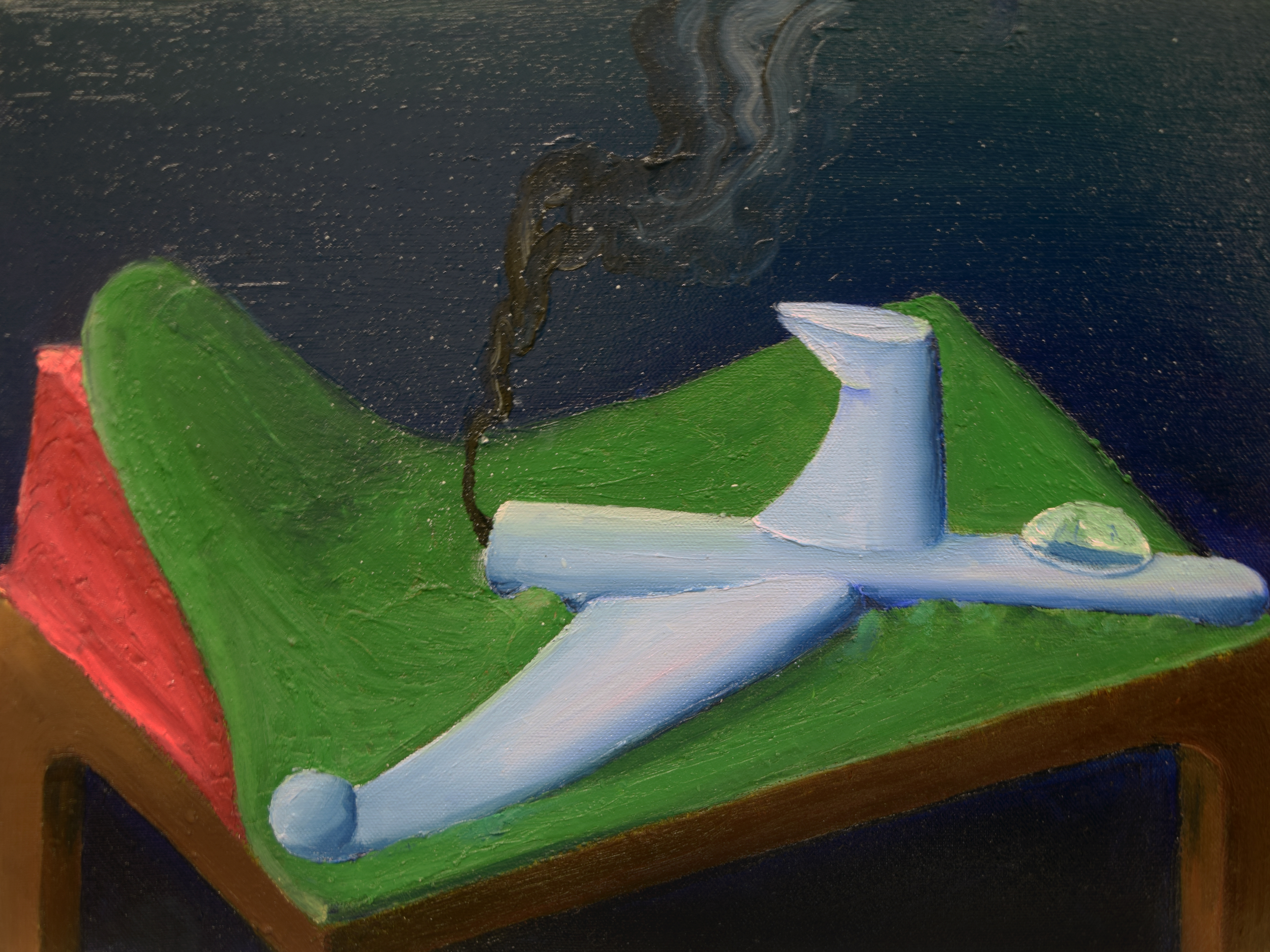

Simulating Fire, oil on canvas, 50 x 30 cm, 2019

Simulating Fire, oil on canvas, 50 x 30 cm, 2019That's an interesting observation - but yes history of art is not generally taught and often students are expected to do their own research in that regard. Personally, I was torn between the option of art school or the academic route but ended up opting for the latter because I thought it would make more sense to understand the context and foundation before pursuing the practical side. It felt rude not to!

I also love that you are referencing miniatures and phenomenology. So without that training, how can you attribute to where you learned your style of painting and how do you conceive the ideas for your work?

I received objective training in painting only in the third year of my BA when Dr. Ian Hartshorne was my tutor. I needed to continue the conversion with him so I went straight into MA Painting course, which he leads. All the paintings included my solo show at Workplace Foundation were painted between February to December 2019, before that I was making a very different set of works.

I have never struggled to choose ideas to start the next painting, I guess I have a highly vivid and streaming imagination. Probably because I'm also sensitive about the inputs as well, I have a prescribed daily dose of standup comedy and classic cartoons for myself. Anyway, the paintings usually start with an epigram idea. I then define an antagonist to it. I repeat the cycle. You could say my practice is an attempt to organize a disciplined image. I carry out the task by paying attention to the surface and employing painterly tools to create complex layers of paint to present a stretched spectrum of paradoxical qualities: soft and rough, thin and dense, immediate and distant, ex-animate and fluid, etc. This approach is employed to offer tension to the surface in order to oscillate between paradoxical poles. Anticipating that, the result would be an invitation to look and observe. In order to succeed with such a task I rely on the train of traditions and histories of painting.

What kind of epigrams provoke your imagination?

By the term "epigram" I meant to describe the scale of the idea; it’s not epic. For instance the painting “Spectre” started with an idea about using a color which I don’t usually use: Orange yellow. Then I defined an antagonist to it: a shade of ocean green. I paint a gradient. The gradient looked like an alien squishy edible landscape so I defined another rival: a concrete object. The ritualistic head statue in the scene felt heavy and static so defined another opponent: a hose-like floating ghost. All the existing elements looked enduring, stable and metaphysical, therefore I defined another competitor: a hat delicately hanging on a twiglet which could lose balance any moment now. I could go on and on about each and every detail but you get the idea. It is simply about the qualities on the surface and the language of painting to carry my absurdist agendas seriously.

Spectre, oil on canvas, 80 x 59 cm, 2019

Spectre, oil on canvas, 80 x 59 cm, 2019The ‘Twiglet’ you describe is a great metaphor for instability, and as you say, balance, much like political trade-offs.

I think there is a sandbox mode to painting. If we understand painting as dialectical, a conversation between the painter and the surface, then this conversation could go on forever, even if seemingly exhausted. The conversation could be paused – temporarily concluded in one painting - and resumed again in another. As if the artist is always working on one painting over and over. In such process the painter might also decide to reference something painted previously, that’s where the repeated motif will become characterized; like the twiglet-like motifs in several works of mine. Perhaps I have found visual solutions which could work and function very well alongside other antagonists. Another repeated motif I usually use is the speech bubbles with faces, besides being aligned with my absurdist agendas; such motifs could easily be seated as antagonistic to a static and concrete motif.

Science of Staging, oil on canvas, 80 x 50 cm, 2019

Science of Staging, oil on canvas, 80 x 50 cm, 2019I know that last year we initially connected working on the second edition of RUNG magazine. I was really struck by your work and also thought it coincided well with the theme which intended to reflect my research in communicating existential risk. Without too much background, I could see how your work was adequately connected to this theme. I thought that the addition of the arrows adds another layer of complexity to the conversation taking place. Can you discuss the idea behind this as a symbol and how you see it linking to risk at all?

The paintings link to the idea of a very real existential threat being just around the corner. When I started to paint them in February 2019 I was reading ‘Capitalist Realism’ by Mark Fischer. It is a critical book about understanding the mechanism of capitalism. Fischer makes the point that such a system needs to produce disaster in order to fill the gap between the regime and the people, whether it is war or something else. Contemplating this book makes this feeling that our environment and the events around us are well scripted. Not to mention my Iranian working class ‘survivalist’ mentality which prepares me to be ready for the worst as if yet another disaster is just around the corner, even when I’m conscious that everything is going great. That’s why the paintings convey a sense of a nearby threat or an awkward displacement by depicting strange theatrical stages, the leftovers of peculiar tests on tables, props and backdrops simulating reality, absurd diagrams providing fictional solutions.

However, on a personal level, I have always been fascinated with diagrams and scientific illustrations since I was a teenager. I got my diploma in mathematics and physics so a lot of such materials were involved in my education. I have recently started to make diagrams from every textual material that I read or write and also every thought process that I have; I have this obsession to put everything into neat and understandable order, which I guess is a very human behavior to try to fully understand something and then document and archive it.

Theorising Conspiracy, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm, 2019

Theorising Conspiracy, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 cm, 2019With the current situation we find ourselves in, at the center of a pandemic, would you say this is something that may be explored in your current or future work?

This crisis we find ourselves in calls for greater emphasis on taking 'existential risks' more seriously than ever and of course these risks are all interconnected with politics and what comes next.

I don’t usually think about how my practice might change in the future, or generally how my life circumstances might change in long term. Every time I planned something for the future, life got in the way and nothing continued as I expected. I’ve learned to live in the present; I do my best every day and the future will be built in the best possible way. However, when I talk about sociality and reality, I am genuinely worried about them. I am reminded of a line from the play Red by John Logan;

‘Mark Rothko: There is only one thing I fear in life, my friend... One day the black will swallow the red.'

-

ghalamdar.com

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Ayla Dmyterko

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED