Sarah Amy Fishlock

Interview by Melanie Letore

Published January 2016

-

Sarah Amy Fishlock is a visual artist. A graduate of the Glasgow School of Art, she works mainly in the field of documentary photography. Her work explores the relationship between the individual and wider social, historical and political realities, the tension between national and familial identity, and the problematic nature of memory.

-

Your projects reveal often unseen narratives: the life of a child with high-functioning autism; the homes of three Iraqi translators who, because they worked for the British government in Iraq, were seen as “collaborators” and for their own safety applied to live in the UK; the people who work behind the scenes of the Citizens Theatre in Glasgow. How far do you see documentary photography as a tool to raise awareness about things that might go unnoticed?

My projects always start out as personal journeys of curiosity. I came across the men who featured in ‘Middlemen’ almost by accident when researching Middle Eastern communities in Glasgow. I was shocked and angry about the process that the locally engaged Iraqi staff had had to go through in order to be resettled in the UK by the Ministry of Defence - a very inconsistent, bureaucratic process that left many people behind. The project became an exploration of the impact of war on these three ordinary families, bringing me face-to-face with survivors of the conflict. I felt a responsibility to represent them as people that have a right to a new life, and are doing their best in a very traumatic situation. Several years later, I think it’s even more vital that these groups are highlighted – negative attitudes towards those fleeing conflict are still very prevalent in our society, and are exploited by western governments. There has to be a counter to that viewpoint, and I think photographers have a role to play in that resistance.

‘Amye & Ahren’ began as an exploration into what it’s like to care for someone with a disability. I didn’t know much about autism until I started the project, so my research forced me to explore a world I was unfamiliar with. The project attempts to reveal the places where Ahren’s inner world and outer reality meet - it’s a very intimate project. One of the elements highlighted by Amye, Ahren’s mother, is a tendency of outsiders to assume that Ahren is a naughty child - because his disability is hidden, people are more likely to make unfair judgements about him. And of course, in recent years things have become much worse for disabled people and their carers, as access to benefits becomes increasingly difficult. Although the project isn’t explicitly political, I do think it highlights the idea of an invisible struggle, and I hope that it encourages the audience to reconsider their own approach to people with disabilities or other problems that aren’t always immediately apparent.

You could say that although my projects are usually personal, intimate stories, there is often an element of bringing something hidden into the light. My projects look at individuals, families or groups as microcosms of wider political and social situations.

Amye & Ahren, 2012

You have said: “ being a documentary photographer gives me the ability to work in an intuitive way that seems completely natural – I like to put myself in unusual and interesting situations and then respond instinctively”. How much do you allow yourself to be intuitional? Does your practice change with each project and do external factors affect the way your work (such as, for instance, the fact that “Citizens” was produced on a residency and seemingly the pictures seem more posed than in other projects)?

The slow, focused, intimate process that I use for personal projects would have been inappropriate for the Citizens Theatre residency, which asked me to engage with staff and local residents, as well as with the theatre building itself. It also presented me with a fixed deadline and set criteria to be met. I saw an opportunity to apply some of my previous experience to new ways of working. I began with a disposable camera project to involve the theatre staff in the residency from the start, moving on to make portraits using portable lights, documenting the theatre’s interiors, and initiating two collaborative projects with community members. The residency was a hugely enjoyable challenge that helped broaden my practice through a range of photographic approaches, spanning documentary photography, portraiture, and the integration of found images, as well as the production and distribution of two photo zines.

My ongoing project Five Lands, exploring the stretch of coastline in north west Italy from where my mother’s family came to Scotland, is on the opposite end of the spectrum. I’ve been working on it for four years, and it’s almost purely intuitive – it’s a series of impressions of a particular place that takes my grandparents’ emigration as a point of departure, but does not have the conventional documentary narrative structure of most of my earlier projects. I’m also working on a second project about my family, focusing on my relationship with my late father. This project has taken me in a much more experimental direction, and is more process based than previous projects.

In the past few years I’ve learned that I make my best work when I’m open to new ways of working, without worrying about what ‘type’ of photographer I am. I think it’s vital to keep refining your practice, assimilating elements of the processes that work for you, and trying to learn from those that don’t.

Middlemen, 2011

I guess this could be asked of any artist, but since we are talking about intuition, projects that are ongoing versus projects that are finished, and since you seem to work in very defined projects, I want to ask: when do you know a project is finished? What is your editing process once you have realised the project is finished?

I look at my work as a collection of ongoing stories, often with overlapping themes, rather than as series of projects with defined beginnings and endings. After I graduated, I thought that photography projects should document periods of time in the lives of subjects, before moving on to new stories. This was probably a product of the pressure I felt to get my work seen and prove my worth as an artist - a feeling that I'm sure is familiar to graduates and emerging artists. I think this pressure is to an extent necessary in such a competitive industry, and at a time when well-paid opportunities are limited, but I think it can also stifle creativity as artists become preoccupied with self-promotion in order to stay afloat financially. There is a constant struggle between the practical realities of being an artist, and the need for time and space to explore ideas to their full potential. In recent years I've started to look at my practice as a continuum, with each new project being linked to and informed by those that came before. I'm also more open to the idea of returning to projects after a period of time has elapsed. In the future I'd like to revisit the Iraqi interpreters and document their children growing up as Glaswegians - woven into their communities from the beginning of their lives, as opposed to their parents’ experiences of isolation during their first years in Glasgow. I’d also love to return to Ahren’s story, and explore how adolescence changes him. I don’t think of either of these projects as finished, but on hiatus until the time is right to revisit them.

It is very interesting - almost as if students/graduates progressively move away from a temptation to package projects neatly, towards a more open, fluctuating practice. This brings me nicely to my next question: in your ongoing (diaristic?) project Five Lands, I am really intrigued and fascinated by the inclusion of a map. There is also what I believe to be an archive photograph; how do you feel these elements change the narrative and reading of your project?

It’s only in the past year that I have started to incorporate articles from my family’s past into this series - my grandparents’ lives as cafe proprietors in Glasgow, my grandfather’s journeys in Africa in the 1930s, and many trips back and forth between Scotland and Italy. This provides a visual link between my own images of modern-day Italy, which are observational and almost meandering, and the story of my mother’s family, which is now part of the larger history of 20th century Europe. There’s something amazing about the fact that these photographs and documents have survived so long - the map that my grandfather, Romolo, made when he was stationed in Africa is over 80 years old. As in many families of the diaspora, there were multiple trips back and forth, to bring over children, to attend family events, to take holidays or plan for retirement. So my grandparents probably never felt at home in either country: there was always a tension, a discomfort that meant they couldn’t relax. Perhaps the photographs helped my grandparents to feel somehow cemented in Scotland. Documentation is important to immigrant families, especially when you are from the ‘wrong’ country, as my grandparents were during WW2 - there is always the fear that one will be called upon to prove one’s identity. I sometimes wonder if my own photographic habits are an unconscious echo of this anxious need to pin things down, to keep from losing things.

I’m still experimenting with the archival images and how they will work with my own photographs in an installation. It can be quite difficult to be decisive about this kind of project as it’s so personal, but I’m content to continue adding to it for the time being - it would be interesting to see how the project evolves over several years.

Do you see your practice as a maker of photo books as an extension of this need to “pin things down”?

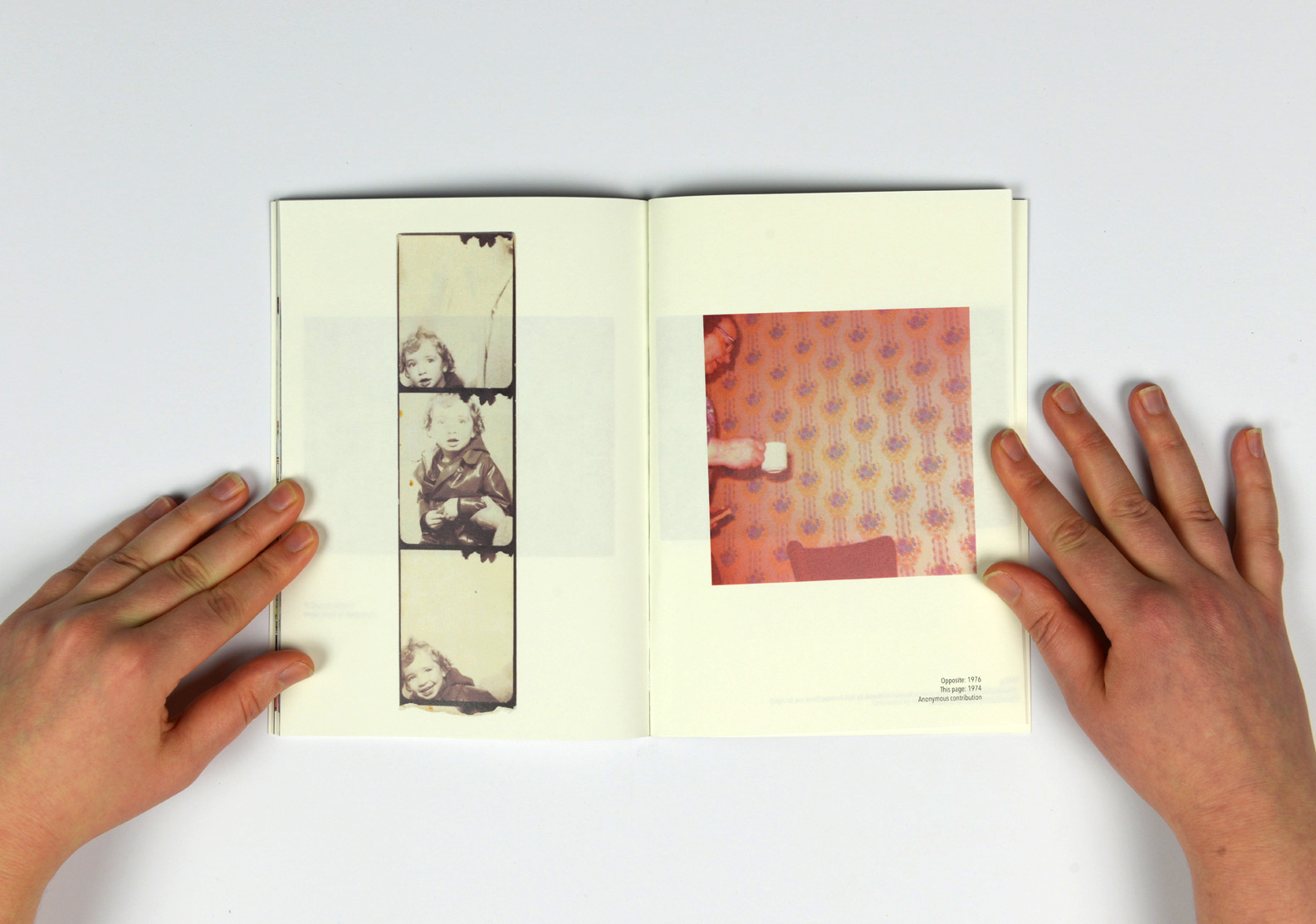

I started making photo publications as a way of documenting my work in an economical way that also allows me to share my projects with the people involved - I love the idea of the people I’ve worked with, from the middlemen, to Amye and Ahren, to the Gorbals community members, having a lasting document of their participation that they can look at in ten or twenty years’ time. It can be difficult to justify spending money on printing as an emerging artist, especially when we can so easily share work for free online, but I think publications are invaluable for taking work to new and sometimes unexpected audiences, as well as creating a physical archive of projects that can be drawn upon for interviews, talks, or as context for new work.

You raise quite a few very interesting points here about the value of self-publishing and of the use of photobooks in photographers’ projects, so thank you for that answer (timely also because of the release of Self-Publish Be Happy’s book in the UK in November 2015). How has Goose Flesh (a zine you founded and which you edit, showcasing photographers based and associated with Glasgow) influenced your own photographic practice as a photographer? As a photo-book maker?

I started Goose Flesh because there are many artists I love in Glasgow and Scotland, who don't often see their work in print because they're still at an early stage of their careers, and don't have the capital to self-publish photobooks, or enough of a profile for publishers to invest in them. Goose Flesh has made me a lot more experimental when it comes to materials - the zine is published on a shoestring and I've had to find a balance between cost and quality. I recently led a zine workshop at Gray’s School of Art, Aberdeen, as part of their Develop North festival in October – the publications produced by the participants were really inspiring, and made me want to experiment more with text and non-photographic images in my publications. I see the skills i've developed through making zines as being easily transferable when the time comes for me to make a more substantial photobook in the future, perhaps to realise a long-term body of work.

A Citizens’ Archive, Edition of 300, 2014

Before I move on to another question about Goose Flesh, I want to take the opportunity to ask about text, since you mention your interest in it. One of the men from “Middlemen” is a calligrapher who helped you with the cover of your publication; another is a translator and translated your texts into Arabic for your book. Can you please speak a little more about how you see their collaboration with them for your self-published photobook?

I wanted the project to be a collaboration between myself and the people I was photographing. I gave the men western names to hide their identities – in two of the cases, these names were actually those given to them by the British soldiers they worked with. I think the reader gets a sense of each man's experiences as they read their stories – I hope that each voice is clear even though I cannot show their faces. Many of the quotes are not explicitly about their resettlement in Glasgow, or their experiences in Iraq, but about things that affect their lives now – the UK job situation, the attitude of David Cameron towards immigrants – as well as more abstract ideas about survival, determination and hope. I worked closely with them on the text to ensure they were completely happy with it – I actually removed a really strong quote at the last minute because it was decided that it would have been too upsetting for family members to read. In these situations I always defer to the wishes of the people I'm working with – I think it's so important not to lose your humanity in the quest for a good story.

The man known as 'Ryan' translated the text into Arabic for me, as I thought it was important for people from the Middle Eastern community in Glasgow to be able to engage with the project. The man known as 'Joe' drew the title for me in beautiful Arabic script. These elements help to make the book a document of the men's stories told in their voices, and elevates them to active participants in the project instead of passive subjects.

It’s also interesting that since its inception, you have invited someone else to write an introduction to Goose Flesh. Are these collaborations due to a reluctance to imbue your publications with a single textual voice? What role has text played in Goose Flesh?

The idea behind Goose Flesh was to create something compact and affordable, a publication that presented photographs with minimal information, allowing readers to experience the images and the links between them subjectively. To this end, I've actively sought out single images, work in progress and observational images rather than 'finished' or conceptual work. I wanted to bring the work out of the usual echo chamber of photography criticism and out into the wider world – so it made sense to ask writers from different disciplines to interpret each series of images in any way they wished. So far there have been introductions by Cayleigh May Forbes, Sean M Welsh, Kirsty Logan and Craig Woods – all writers with a link to Glasgow, and all with a totally different way of writing. This collaboration has resulted in some great unplanned elements too – for example, Kirsty Logan read her introduction at the Goose Flesh 3 launch at Trongate 103 in 2014, something we don't usually see at photography openings. I really want Goose Flesh to be a cacophony of creative voices, rather than a publication governed by an overarching narrative.

Five Lands, 2011-present

Where can I look forward to seeing your work in 2016?

I'll be using the funds I was awarded through the Glasgow Life Visual Art and Craft Award in 2015 to produce two new publications, one documenting a short project I did with a youth club in Glasgow, and the other a selection of images from Coney Island, New York. At the moment I'm working on a few long-term projects which are in the development stages, so I'm really looking forward to continuing with these during 2016.

-

Recent exhibitions include Photo UK India: Origins, Delhi, India, Landskrona Foto Festival, Landskrona, Sweden, Goose Flesh: Stock Take, Street Level Photoworks (Gallery 103), Glasgow and Magnum/ Ideastap Photographic Award 2014 (Finalist), Old Truman Brewery, London.

-

If you like this why not read our interview with McGilvary/White

-

© 2013 - 2018 YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED