Sofia Hallström

-

Interview by Caitlin Merrett King

-

Published in November 2023

-

We met in Marseille a few weeks ago when I was visiting Porous Cities, the group exhibition you curated at Feria for South Parade, a gallery based in London as an off-site exhibition. Could you tell me how the exhibition came about?

The exhibition came about through South Parade who invited me to curate the show, whilst the gallery was also participating at Art-O-Rama fair. The show at Feria, titled Porous Cities was in response to essays written by Walter Benjamin in the 1920s during his travels to Marseille and other European cities. He wrote extensively about urban spaces having the ability to fuel feelings of loneliness and isolation, but also having the capacity to improve lifestyles. He described Marseille, Moscow, and Naples as ‘dispersed, porous, commingled’ places as a result of their urban design. Urban porosity can be viewed as encompassing both the spatial configurations and the activities shaping the way people experience communal spaces. All of the artists in the show explore this with different approaches, whether through materials, process or through the conceptual underpinning of the work. Alongside the physical show, I created an animation of the exhibition whereby each work is displayed in a different virtual landscape.

Porous Cities, installation view, South Parade at Feria, Marseille, 2023. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

All of the works do have a real materiality of the city, whether it’s Waj Hussein’s ‘menace of the sex deviate’ (2023) works that could be wheat pasted onto a lamp post or Pisces Don’t Drown (2022) by SAGG Napoli, that feels like a dare devil’s advert for the city, or the infinite travelling possibilities of the flaneuse/r. I’m interested in your positioning as the curator as someone not from the city of Marseille – how was this experience and how do you feel you might have approached the show if curated in say Moscow or Naples (other cities referenced by Benjamin) or London, where you are based for example?

I was very aware or wary of making any sort of commentary on a place that I’ve never been to before. Having read through Benjamin’s texts, I felt a familiarity with Marseille through his comparisons with Naples, a city that I’ve spent a lot of time in and have family relations who live there (my grandmother was from Salerno, a neighbouring city to Naples). With this in mind, the texts were used as a starting point, from which in-depth conversations with each artist brought about different conversations and ideas of how each work could work in dialogue with each other, bringing a multitude of ideas together. Conversations with Ryder Morey-Weale (an artist based in Marseille) for example, who uses a lot of packaging materials from imported goods coming through the city port in his work, I understood Marseille as a place of movement (of people, goods, ideas etc.), so it seemed to work that there was a range of artists, each working in different cities or with different mediums. In this respect, I would have approached the show completely differently had it been in London.

With this idea of movement in mind, I like theorist Giuliana Bruno’s exploration of the connection between motion and emotion, encompassing bodily movement and image dynamics, alongside various modes of travel and its ongoing significance in contemporary interdisciplinary studies of visual culture. She also explores how–in our visually driven era characterised by transformations in materials and media–does materiality find its role, and how is it brought to life in virtual representations which is partly what also prompted the virtual exhibition.

The virtual exhibition, also titled Porous Cities, is a video work made by you that was installed within the exhibition on an iPad by the entrance as well as being available to watch online. It reminded me of how during the pandemic, widening access was such a huge topic of discussion with galleries and artists making work available online but this has largely fallen to the wayside now. I like how the virtual exhibition acts as both an abstract exhibition guide and a reimagining of the exhibition as well as an individual artwork with its enjoyably nostalgic, early-2000s Second Life aesthetics. It positions you as both curator of and artist within the exhibition which is something that you’ve done in an previous exhibition at Good Weather in Chicago, co-curated with Harlesden High Street, London. What was your intention and experience of this porosity(!) of roles?

I think there are many natural overlaps in terms of the process of curators and artists. I moved to London last May to start a residency with PM/AM Gallery and the residency studio was in Harlesden. Towards the end of that time, I had been working closely with Andre Morgan who lives in Harlesden assisting him with paintings for his Liste, Basel presentation last summer. With the show at Good Weather in Chicago we wanted to showcase a duality, between two artists who worked in very different ways. The show was two-part and presented in two offices: one old and falling apart, and the other completely new and functioning.

For the show in Marseille, I had made a series of work in 2021–2022 of fragments of walls from Kyiv in Ukraine that I thought would bring an interesting dialogue into the exhibition. The paintings reference monumental public artworks of the type found across the former Soviet Union, and draw from a stock of socialist realist imagery. The work was inspired by a visit to Ukraine (my brother was living and working in Kyiv in 2018), where thousands of Soviet murals and mosaics have been destroyed following the passage of a ‘decommunisation’ law in 2015. The Quadrant paintings (one of which was presented in Porous Cities) recall this shattered corpus of propagandistic art, decontextualised and denuded of its ideological content.

Quadrant I, 2021, oil on panel, 98 x 98cm. Photo: Flavio Palasciano

There was something quite eerie to me about Quadrant I (2021) that features in Porous Cities when I first saw it, something about the occluded imagery and pervasive red, and this makes a lot of sense to me now hearing this explanation. It feels like it’s holding a lot and the closer you look the more you can make out of the communist imagery, the ears of wheat for example. Within your painting practice you are often pulling imagery from a variety of sources and collaging it to make very complex and vividly-coloured pictures that have quite a nostalgic quality (for want of a better word). How do you select your imagery?

Sometimes people bring up that I work with a lot of different mediums, tones and voices. I like to take from something that already exists (whether this is a photograph or something that I've read) and reimagine or recontextualise it to make something completely new. I draw from a range of source materials, from architectural references, to political histories and narratives. Many of these materials carry personal undertones, for instance a series of paintings that I am currently making incorporates a collection of letters that my Irish grandfather wrote to Tadg Collins (a relative of the Irish Revolutionary, Michael Collins). I weave these elements into a broader context, using them as materials to discuss more significant themes. It’s important for me to have an expansive approach to painting, one that challenges established norms associated with classical paintings and its loaded history, especially as a woman painter - painting shouldn't play by the rules!

Absolutely! I like that painting as a medium has the capacity to be wily and slippery, to be progressive and responsive like all good ideas. To literally zoom in, there is often a segmented or gridded quality to the surface of your canvases and the titles of your paintings, such as Quadrant and Quartile also suggest a regular geometrical division of a flat plane or area. A quadrant is also a tool for measuring altitude in astronomy and navigation. Where does this aesthetic interest in fragmentation stem from? I can see how the visual directly links to the process of stained glass production which you have done in the past.

Over the lockdown, I was awarded an art-research course to study maps at The Warburg Institute. I am fascinated by Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas; an inventory of Renaissance art and cosmology that seeks to connect historical fragments to exist fluidly and without separation. As Warburg describes it the Atlas is an embodiment of movements through and within; a distillation of the ‘dynamics of exchange of expressive values.’ My practice seeks to achieve something similar.

Taking cues from anthropology and history, exploring how different societies at different times have sought to situate themselves in the world and order their existence by schematising the space around them, I am interested in these tools of measurement, which are often tied up with inherent biases. For instance, we tend to think of maps as precise depictions of space, but they haven’t always been that way and arguably they still aren’t! For example, there was a controversy among cartographers in the 1990s about how the traditional world map massively underrepresents the size of the Global South (particularly Africa) because it was designed for the needs of 16th century European explorers. Even something as logical and scientific as the map of the world actually involves a negotiation between external space and the internal horizons of a given society or individual at a given time.

Having spent a lot of time growing up in Southern Italy (where my grandmother was born and raised), a part of the world that is built upon layers of fragments from the past, I am interested in how a culture can grow and transform between and among fragments. Glassherd, is a sculpture composed of cut glass segments held in a steel frame. The glass has been treated, soldered, and superimposed with photographs taken in the 1960s by my late grandfather in Pompeii, Herculaneum and Paestum, Roman architectural sites near Naples. The segments have been painted with details from frescoes and mosaics from those sites, and are set in a frame which recalls the rebar steel rods used to support crumbling masonry. The work explores themes of loss, fragmentation, remembrance and forgetting.

Telemarketing Scandal ‘96, Good Weather (off-site) Chicago, in collaboration with Schlep, curated by Linda Mognato, 2023.

Telemarketing Scandal ‘96, Good Weather (off-site) Chicago, in collaboration with Schlep, curated by Linda Mognato, 2023.

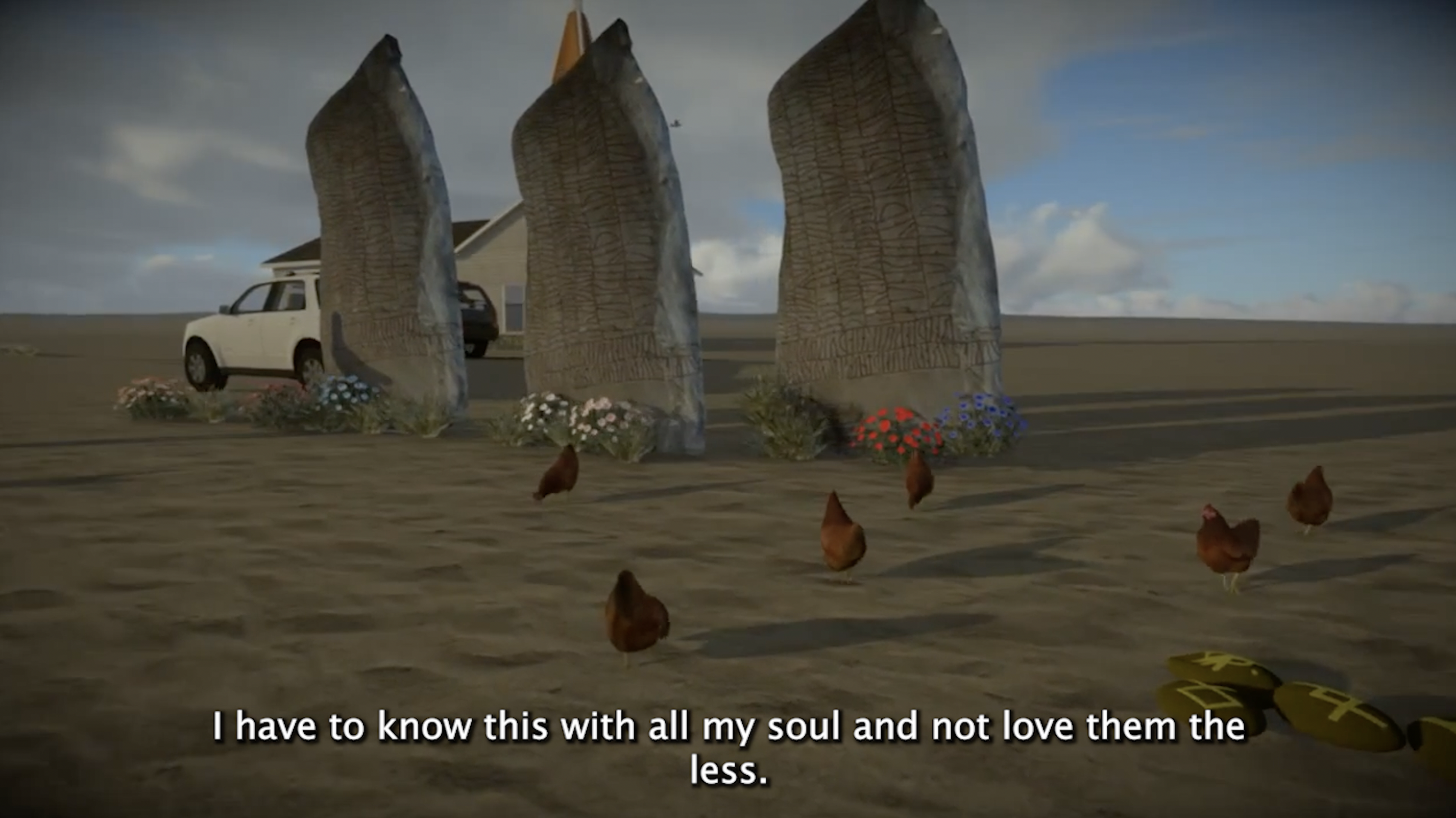

It's interesting then to think about delineation of space and cartographies in relation to your latest video work, Chance that was shown at Minor Attractions last week during Frieze week. The film has a voiceover reading Simone Weil's Gravity and Grace alongside several scenes of expansive landscape featuring large architectural structures and characters going about their daily business, such as the two figures reclining in the field in front of the aqueduct enjoying a McDonald's. The pairing with Weil suggests an openness to receiving, she said that attention is the rarest and most pure form of generosity. What was the starting point for this new work and where does your interest in Weil come from?

The work explores themes of consumption and the production of desire. I have long been interested in Simone Weil’s ideas and writing. She was a philosopher, activist and committed to a vision of social justice. I am fascinated by her notebooks, made up of fragmented sentences and drawings. In Gravity and Grace, Weil seems to accept the very uncaring and indifferent aspects of this world. In the text, desire is not condemned but rather seen as a potential avenue for transcending the limitations of impermanence and chance. She offers a unique perspective that encourages individuals to examine their desires and the spiritual possibilities they hold in a world characterised by impermanence and chance events.

My interest in making videos (in part) stems from Giuliana Bruno’s writing and her interest in the embodiment of the gallery viewer – the experience of looking at a sequence of moving images has similarities to how the viewer walks through a gallery or museum – looking at collections of things and forming connections between them. Previous videos, such as ‘Diverso’ (shown on the Piccadilly lights with Circa in 2020) explored the qualities and divisions of time: the moment, the duration, historical change. This work was made during lockdown and an attempt to document the microcosm, at a time of what felt like world-historical rupture. I had just read Carlo Rovelli’s ‘The Order of Time’, and was interested in the idea that our experience of physical time is mediated through memory - which is itself an entropic, creative process. It seeks to capture something of that chaos and entropy, and by so doing, to chart the physical reproduction of the world from moment to moment.

Chance, (still), 2023, 6 mins 31 secs

_

Sofia Hallström is an artist and writer based in London. Selected exhibitions include ‘Allow Cookies’ at Kupfer, London (2023); ‘Telemarketing Scandal’ at Good Weather, Chicago (2023); ‘New Contemporaries’ at Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh (2022); CIRCA, Piccadilly Circus (2020).

Porous Cities was a group exhibition of work by Sofia Hallström, Waj Hussain, Luca Longhi, Elijah Maja, Ryder Morey-Weale, SAGG Napoli, REDEYE & Camille Yvert at Feria, Marseille from 31 August - 9 September 2023, organised by Sofia Hallström for South Parade, London.

︎ @sofia_hallstrom_

sofiahallstrom.com

︎@caitlinmerrettking

caitlinmerrettking.cargo.site

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Yoojin Lee.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED