Yael Roberts

Interview by Liat Rosenthal

-

Published in September 2022

-

Yael Roberts uses printmaking to create large scale installations that explore myth, dreams, impermanence, landscape, nature. Our conversation discusses mark making, collective trauma dreaming, Jewish liturgy, and what it means to find your feet as an artist post pandemic. A version of this conversation appeared on Cubitt Community Radio on 26 August 2022.

-

I'm Liat Rosenthal, senior creative producer at Tate Modern and programmer of the Tate Lates and today I am here at Cubitt Studios and I've been invited to join Yael Roberts in her studio to be very nosy about her practise in printmaking. It's quite incredible to step off a busy city street and end up in a smaller space which is bursting with shapes and colors and print. Let's kick off with the studio. It's quite special to have a studio in the heart of London.

Yes! My studio is a womb. It's a place where I can play and be experimental and have no rules. I've been in this space for about three years now. It's my home. It's an amazing space and a very special community. Studio practice is not always fun, but I can be in my creative flow here and make the work that feels right to make. That brings me joy.

Your work has a very sweet, childlike naivete to it. And it’s also incredibly textured and layered. You can see there's a real joy in the materiality of working with the sketching and the carving into materials.

I stopped fighting it. I've been making work since I was five, and I looked back and thought, why am I trying to be something that I'm not? Why am I trying to make work in a more formal context? I want to do the work that I want to do and this is what's emerging. So then why don't I make it? Why do I need to change what's coming out? The work will naturally evolve and I want to follow that rather than trying to make it a certain way.

In March of this year we opened an exhibition at Tate Modern about global surrealism and we worked on an overnight event at Tate Modern. It was an exciting research opportunity for us to look at different artists working around the practice of sleep and dreaming. Your work falls into a much wider, deeper, richer history of artists who've drawn inspiration from dreams. When did you become interested in dreams?

It started during the pandemic as I was exploring new relationships to landscape and land. Right before the pandemic, I moved into this studio and started these large scale relief prints. They started off exploring ancestry and the climate crisis and have recently become more interested in mystical places, and that connects deeply to dreaming. I do dream my work, so I'll have dreams where I'm in the work. Either the whole world looks the style of the work, but lately with the current work I've been making, I'm in the landscape and it's not stylized; I’m physically in a “real” version of it.

What does it feel being in them when you're in your dreams?

It's so nice - it's like going swimming! These works in particular have this really soft gold quality, muddy, and you're able to be in them and walk from the different bits of the work to the other bits of the work and encounter different people. I can visit the same landscape on different nights and then I'm in different corners within the work.

Moon (Child) at Lumen Crypt Gallery. Photo by Ben Deakin.

Moon (Child) at Lumen Crypt Gallery. Photo by Ben Deakin.Let’s talk about your moons. I'd like to hear a bit more about what these moons mean to you specifically from a Jewish lens.

These sculptural forms are meant to be read alongside the landscapes. I create additional ghost prints from the landscapes and those get collaged onto the plaster forms. I see the moons as a way of marking time. Being a descendant of immigrants and having moved to this country myself seven years ago, I’m interested in the ways in which throughout history, my ancestors have fled to different places because of persecution. I recently rediscovered this word in Hebrew, ‘lun’, which is not connected to lunar, ironically. ‘Lun’ literally means to sleep, but only for one night. And that’s a huge experience my family has had of sleeping places for a night, moving from place to place. I'm always passing through.

(The) Last Summer and Various Moons. Photo by Ben Deakin.

(The) Last Summer and Various Moons. Photo by Ben Deakin.You did a Masters in printmaking at Camberwell which you finished in 2017. Why print?

I took a printmaking course at university after refusing to do any printmaking in high school. I got really into printmaking immediately because you can plan something but so much is up to chance and that really works for me and my practice. I don't know what's going to come out, but also the process works with the content I’m exploring and I may add imagery on the day and see what emerges. The work I did around the Holocaust and trauma with Tamara Micner felt very relevant for the ways in which our lives leave impressions on us and prints on us and the ways in which we leave impressions on other people.

Your whole body of work is so infused with your Jewish identity. You also work as a Jewish educator. Your knowledge of Jewish liturgy is so rich. Can you unpack that for us a little? How do you approach it? How do you come at it and how does it sit within the current context of working as an emerging artist in London?

I grew up around a lot of bad Jewish art. I want my work to situate itself also within the contemporary art world. When you look at my work, if you didn't know my background and context, you wouldn't immediately think, oh that's Jewish art or she's a Jewish artist, but it is infused with my Jewish identity.

The Trauma Documents (All Okay) collaboration with Tamara Micner. Photo by Ben Deakin.

The Trauma Documents (All Okay) collaboration with Tamara Micner. Photo by Ben Deakin.Can you tell me more about this process of creating Nine Days?

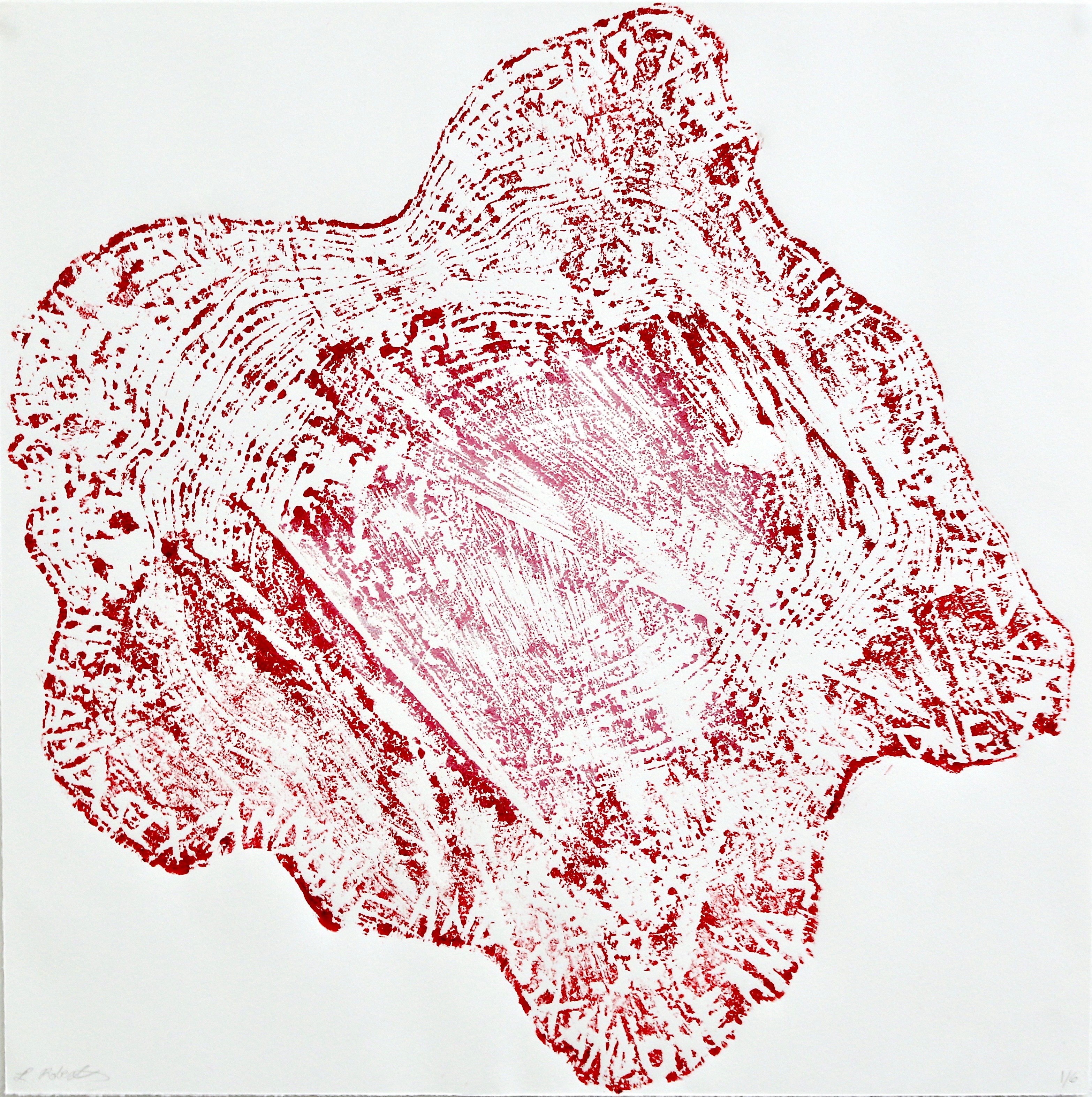

The nine days was a project that I did when I was in residence at the Fish Factory in Cornwall and it was around the time of the actual nine days which are nine days of mourning over the Jewish summer in the lead up to Tisha B'av which is the day that marks it's a Jewish day of mourning marking the destruction of the temple. I had a residency there and each day of the residency it wasn't actually on the 9 days, but I did a print. The prints marked my own feelings of mourning and destruction about our current world and the climate crisis and the temple that's being destroyed. This work that we're looking at now is going to be for a show, the theme of which is “in the field” because following the 9 days of Tisha B'av when the temple was destroyed, we move into the Jewish lunar calendar’s month of Elul, which is a month leading up to the high holidays. There's a Jewish spiritual teaching that during Elul “the king is in the field”. The king, being God, leaves the palace and goes into the field, and to me, that's the destruction of the temple. Suddenly we have this more expansive Jewish practice, which stops being temple centric and stops being about a king in a palace and becomes about being in the field. In a sense over the past year, I've gone on that journey as an artist, moving from that period of destruction and into a more generative period where it's about what it would it mean to find the divine everywhere.

I also wanted to ask about a personal interest of mine, which is Jewish mysticism and how that relates to your work. Do the dream landscapes that you create overlap with Jewish mysticism?

Not overtly like with Anselm Kiefer’s work for example. I'm a mystic and I've had mystical experiences in landscape and that's what I bring back to the work. Speaking of Cornwall, Ithell Colquhoun is a painter who wasn't Jewish, but hung out with a whole group of Jewish artists in Lamorna. Her work is super mystical, very colorful and abstract as well. Some of it is quite clearly linked to Kabbalah and sephirot. My work isn’t able to be mapped in the same way. Although it asks the viewer to assign meaning, it also multiplies meanings and resists the assinging of any systems to it or categorisation.

Moon (Growth) at Safehouse 1. Photo by Klara Vith.

Moon (Growth) at Safehouse 1. Photo by Klara Vith. I see a lot of cross referencing in your work - it's multi-hyphenated. There's links to different things in the mark making and the imagery. All of the work references all the other work.

Each of these is printed from the same plate, a lot of them are printed from the same plates and all the carved marks are the same. But then the drawn marks are repeated as well. I'll use similar drawn marks in different works and then I'll reuse them. The imagery reoccurs. I feel that these larger prints are scrolls that can roll up and unfold. Even though they don't necessarily bear loads of textual references or have text in them, they are stories that refer to each other.

(The) Last Spring and Various Moons at Lumen Crypt Gallery. Photo by Ben Deakin.

(The) Last Spring and Various Moons at Lumen Crypt Gallery. Photo by Ben Deakin.I work with a lot of young creatives and emerging artists and it's very difficult for people to make that transition post MA to settling into studio practise, particularly in Londonn, particularly now. As the city has changed so much, as we emerge from the pandemic, what would be your advice to artists who just graduated?

What's worked for me is continuing to come to the studio. At some point I realized that anything I did in the studio was my practice - it was all part of the making. Right now we're recording and the recording stuff is on the wood that's going to become the print. And I started to print from my table tops and also, embracing an expanded practice. After I stopped thinking my practice had to go in a certain way or certain direction. It has gone in a direction, but that's happened quite naturally. The main advice is, whether your studio is your bedroom or a studio or your garden, go to the studio. That can mean different things for different people, but wherever the studio is, the work happens.

One and Six from Grassroots Jews Comission.

One and Six from Grassroots Jews Comission.-

Yael Roberts was born in 1992 in St. Louis, USA and lives and works in London, UK at Cubitt Studios. Yael has an MA in Visual Arts: Printmaking from Camberwell College of Arts. Upcoming shows include In the Field at Ein Sof Gallery, London, and Cubitt 30 at Victoria Miro Gallery, London.

︎ @yael_roberts

yaelroberts.com

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Alice Bucknell.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED