Ama Dogbe

-

Interview by David John Scarborough

-

Published in November 2023

-

Ama Dogbe is a British-Ghanaian artist who builds video games, digital animations and audio-visual installations exploring autobiographical and utopian themes. Her recent work uses interactive virtual world-building as a tool to examine family, identity and the internet. She has created digital forests, sky mazes, and gleaming platforms that audiences can explore online.

-

I thought we could start at the beginning with a piece of work you made whilst you were studying for your undergrad at Loughborough University. The project was called Liminal World. It featured a video game, trailer and installation of small sculptures and posters. We've talked about this before, on entering the exhibition, I found the work deeply moving. And you revealed that part of the work featured manipulated voice recordings of songs and prayers of your family members. Could you tell me a bit more about the importance of home and family in your work?

I mean, it's sort of everything I guess, because that's the starting point. The reference is home. I guess it's what makes me, me. Who I've grown up around, where I've grownup around and the people that have shaped me. Liminal World was an exploration into this idea of mind and body and dissociation. Things that can keep you grounded and things that bring you back, to connect the two. Because I am Ghanaian, and so many references come from Ghana, it kind of always feeds into my work in a very natural way. A big reference was the book Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi. And in that, they look at Igbo cosmology. It's something that I really connected with. It's a beautiful book, I think everyone should read it. How do you get back to who you are? And what does that mean? I think family does that for me. It pulls me back.

Are You Coming To Church, video game still, (2023) Image courtesy of the artist.

The digital commission that you've made for Spike Island titled Are You Coming To Church?, seems to me to be one of the most realised games that you've made so far. And it somehow manages to be super chaotic, and super reflective. Can you talk me through the process of developing the project?

I love that. Chaotic and reflective. Because I think that is a lot of the process. There are so many ideas. There are so many things. I often use mind maps. I think my mom is a big mind mapper and she's instilled it in me as a way of distilling thoughts. I remember at uni actually exploring this idea of Rhizome Theory and thinking about it as the roots of a tree and how it just continues forever. It's kind of unfathomable. I think that's often how I think about a train of thought. It's something I really enjoy exploring in my work because the chaos is true. When you're making a body of work, and you're trying to refine a piece, you need to cut the ends at some point, because otherwise, it can continue forever.

With Spike Island, I've worked with someone called Jasmine Morris, who's just an amazing artist, but also an arts educator. Jasmine works in the Creative Computing sphere. The sessions really helped me to think about how to create a narrative. In our chats we kept coming back to core themes and realising them. More mind maps were happening. I used Twine for the first time in this project, which meant that I thought about the words more as well. Twine makes you imagine it in a much more logical way that lends itself to the way you then make a game. But in every game, I don't like the end, I don't want there to be an end. So I aim for that cyclical nature because I think it feels more organic to that stream of consciousness and that chaos. It's like, this is the theme that you start with, but then it's you go off to here, and you think about that, and then you go off to another tendril. But you keep coming back to the fact that there was a core theme. And it all relates to each other in a natural, organic, cyclical nature, which is similar to the way we think.

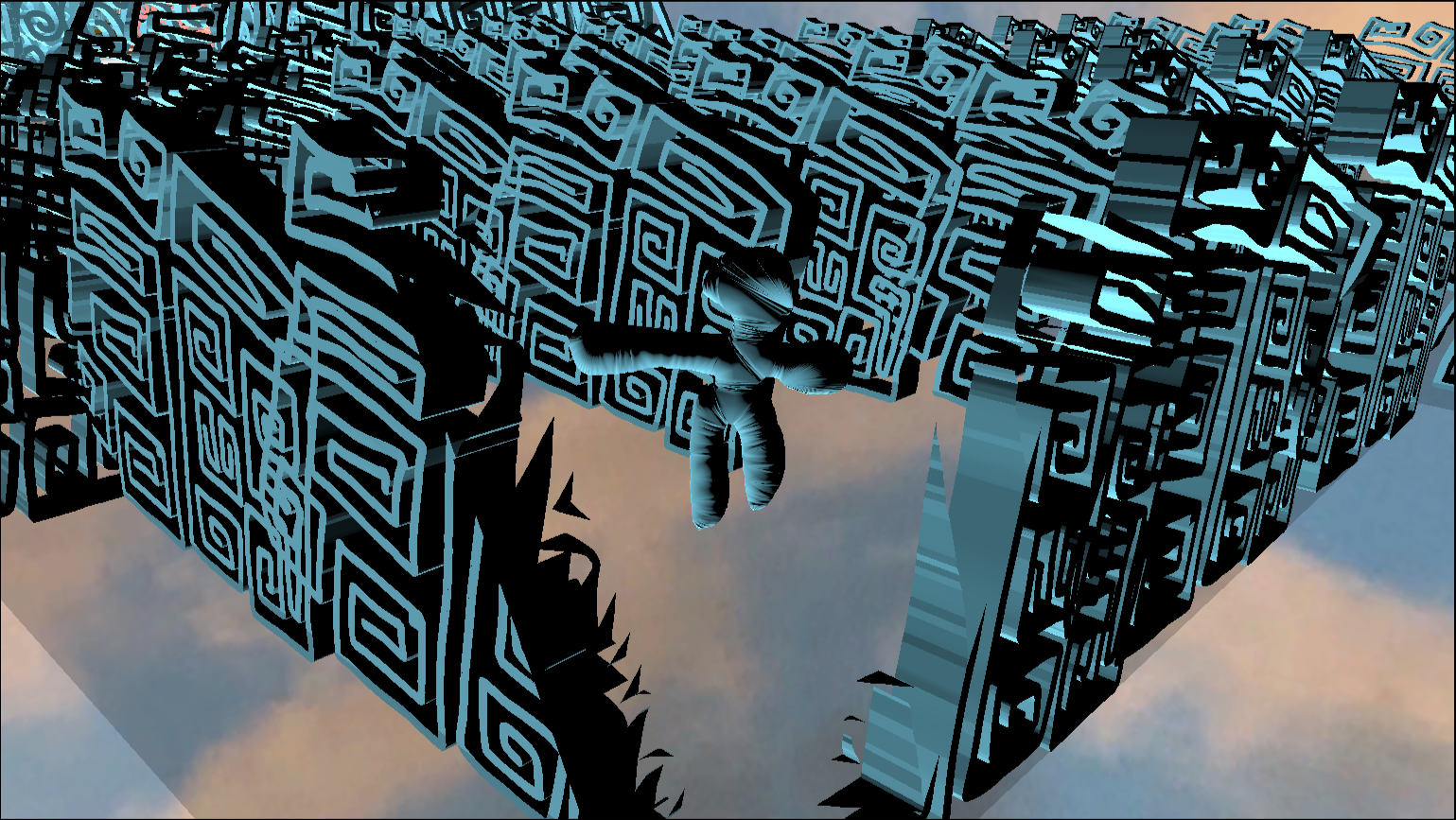

Alien Invasion, video game still, (2023) Image courtesy of the artist.

Alien Invasion, video game still, (2023) Image courtesy of the artist.I think how you used text prompts in the game works so well to engage the viewer and build narrative and activation. The text is a new feature, but right from the start, I'd say lighting seems to be super important. Could you tell me more about the role of light in your work?

It just is. It's the medium of 3D animation and working digitally. I use software called Autodesk, Tinkercad and Autodesk Maya. You're working in a black space, essentially, and then you have all these tools that are tools for lighting. You just plop them in and suddenly you have such specific control over this environment, and lightning is sort of everything. Using blue actually came from Tinkercad because when you use Tinkercad it automatically makes it this blue colour. One of my favourite colours is Prussian blue. I think it's just such a beautiful colour. And then also, there's a film called We The Animals. It had a lot of images of a home, but with the light turned on inside, and viewing it from the distance and this, like warm fuzzy honey amber glow. You can just keep playing with the way the light hits that space. And then when you change the texture of something, the way the light shines on it or bounces off, it is different, like whether it's matte or reflective or see-through. Often I'm trying to go for something comforting.

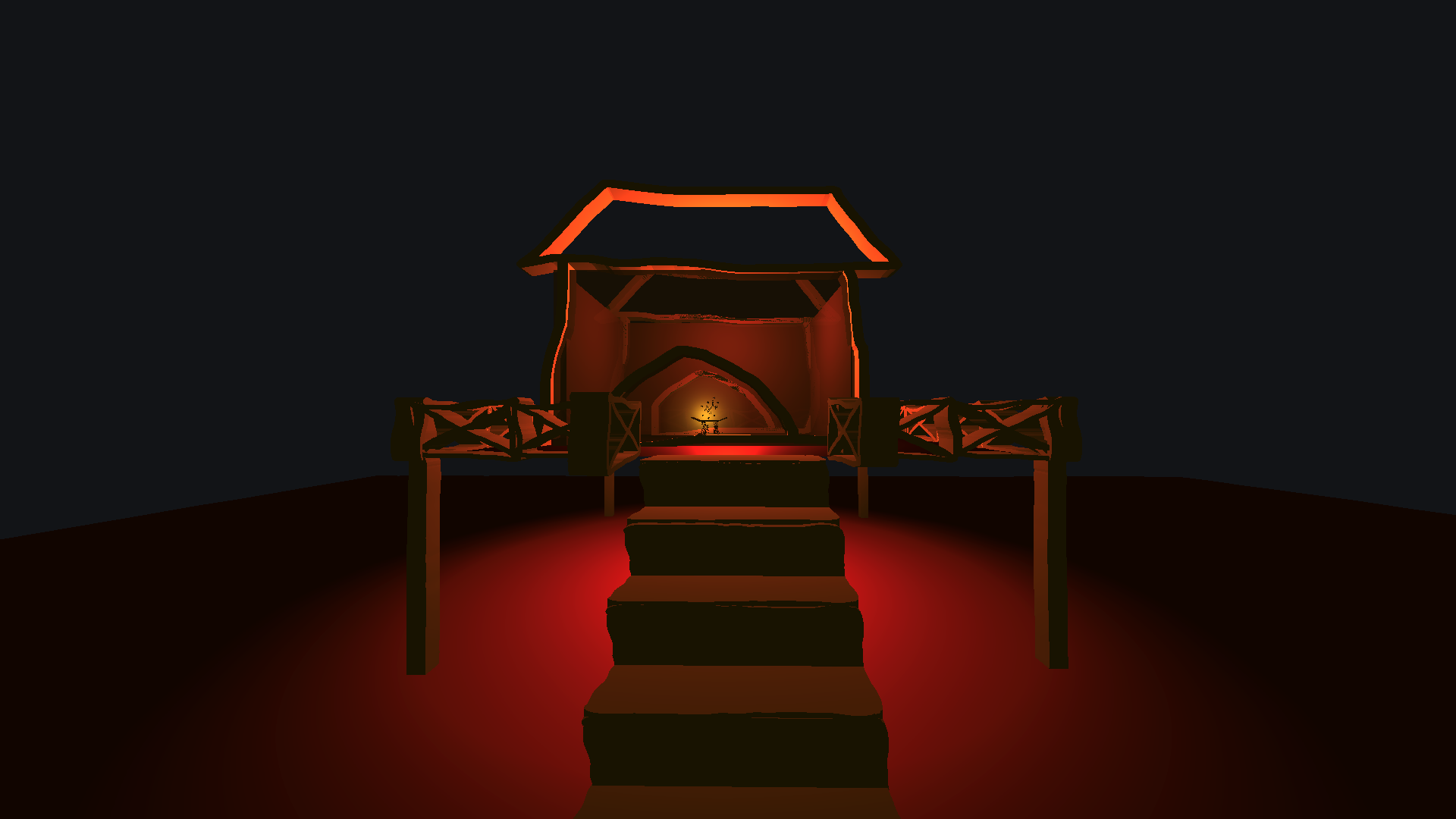

Underlands, video game still, (2023) Image courtesy of the artist.

What would you say were the challenges in making the work for Spike Island?

The concepts are quite challenging. It's probably the game that I've made where I am apprehensive about how it'll be received, how people will take it, what people will think. Often, I don't necessarily think about what is being misconstrued. But I'm thinking that with this one, and I try not to let that stop me from doing the work I want to do. Because I've borrowed iconography from various religions and a big part of it is spirituality, it opens questions and opens spaces for people to have big opinions and that makes me nervous. But then it also doesn't, because if I then have a conversation with someone, then the conversation is going to be interesting. The way I make work is just from reflection and observation. And so I can just have a conversation with people about what I'm thinking. It's not necessarily complicated. I'm challenging myself to not change the way I would make the game because I'm scared of other people's perception of it.

We've talked at various points about how much as an artist you do or don't reveal of yourself, or how you might recoup some of that stuff if you've over shared or what challenges you might need to, you know, reveal a bit more if it's necessary to the work. I think that's an interesting place to be operating out of. As part of our current programming at Modern Painters, New Decorators, you're exploring signs and symbols through a series of commissions. This has been an early part of your practice, which incorporates Adinkra proverbs and, as you mentioned before, Igbo cosmology. For those that are unfamiliar with these symbols could you explain how they inform your work?

It's just imbued in the culture. You can't grow up as a Ghanaian and not know what an Adinkra symbol is. Probably like, the first pair of earrings you get will have Adinkra, or you'll be dressed at some point in clothes that will have it there. It's in your house, it's everywhere. They have meanings that have a long history, but I don't think I necessarily engage with them in that way. What do I take from it? And what have I distilled from it? And I think that is the interesting thing about signs and symbols. As much as there is a meaning there that someone intended to have, you don't necessarily end up being able to have a conversation with whoever made that symbol. People have Signet rings and family coat of arms. For me, the Nkonsonkonson, which is what I have on a necklace, and my mom has it on a necklace, and my dad gave it to her, it's my favourite one. But it's only my favourite one because it's one that my mom had, and then one that my parents gave me and they could have given me a different Adinkra symbol. And that then probably would have been my favourite one because that's where it comes from for me. In terms of just symbols in general, I love maps, I've always liked a symbols key. I think there's something kind of magical about symbols and how obvious they can be and also how ambiguous they can be.

Liminal World, video game still, (2021) Image courtesy of the artist.

At Modern Painters, you developed a piece of work through working with young people and families. And you often work collaboratively with musicians and artists, including myself. Why is working collaboratively important to you?

Well, I guess there's only so far you can get with just yourself. It's just nice to be able to open your work up to other people's influence. Losing that sense of control. Because often within making games or making 3D animations, I am the controller. I get to decide this and decide that and make this and decide which parts of a world you get to see and which parts you don't. So there's a nice element of being able to recognise spaces where I can not be the one that's always in control and open that space up to other people. I'm not musically talented in any shape, way or form. So I was always going to need to collaborate with people on sound. I can come up with all these ideas or thoughts or like, intentions, but once I've offered an idea I can just leave it for that person in their creative practice. I do like to be picky with who I work with because I also want to know that they get me, my references, get the style, get the ambition, and get the drive. In terms of working with the general public, there's something nice about getting people to work with the medium I work with because I think people often don't have that opportunity. It's nice to see what other people do with the same tools. The workshops were so fun and I want to do them more. It's a simple process, it's very open. You can do a drawing, you can make something out of modelling clay, and then very quickly see results. I collaborate on a level with strangers. I have so many recordings on my phone. I don't necessarily know who or what it was sometimes, because it'll be like, a little girl running past the window, and I could hear her from the top of the road singing a song. Collaboration can happen on so many levels and just being open and intuitive to when it feels right. Because it offers something to the work that I am out of control of, but also so in control of because I get to pick who I collaborate with.

Are You Coming To Church, video game still, (2023) Image courtesy of the artist.

I thought we could end by talking about the game ‘Underlands’, which we made together for Fermynwoods Contemporary Art as part of their Xylophobia program. In making the project, we talked about virtual spaces acting as safe places to examine fear and process grief. As a starting point, I wondered if you could speak to this idea.

I think I often use drawings as a way of processing stuff. And often in times of crisis. And if I don't take it any further than a pen and paper, it stays where it is, I don't process it necessarily. It gets something out of my brain, but I don't then develop it and pick it apart. In the process of turning something into a digital asset, and then putting it in a safe space, and taking care of this thing that you've now made, and caring about the lighting, and thinking about what sound goes with it, and thinking about the words that you associate with this thing, you then have to pick it apart in a way that I don't do when it ends as a drawing. With working digitally, it goes off into the ether a little bit. As much as I then get to control how it moves within a virtual world, it's separate so I can think about it with a different perspective. It's isolated, it becomes almost imaginary. But still so real. Because it comes from something real, something painful, something joyous. It comes from real emotion. But, there's an element of removing it from the physical and into the virtual that allows this abstraction, pushing the emotion across without being too literal. Yeah, I guess it's a space that you have complete control of, whereas in the physical you don't. Working on ‘Underlands' with you was a really interesting process because I think we lent ourselves to each other's practices in various ways. Because we were both processing similar emotions, the way the final outcomes were generated we were still searching for that feeling and making it tangible in that virtual space, where it's so obviously tangible in reality because we're feeling it physically, mentally. But in a virtual space it's a blank space, you know, so how do we then make all of what we feel on this level, into that level, and offer a space to really dissect what the lighting looks like in those spaces and what grief feels like and what it can look like.

Liminal World, video game still, (2021) Image courtesy of the artist.

-

︎ Play ‘Alien Invasion’ HERE

︎ Play ‘Are You Coming To Church?’ HERE

︎ Play ‘Underlands’ HERE

-

︎ @artyfartyama

amamaisie.wixsite.com/ama-dogbe

︎ @mpndprojects

modernpaintersnewdecorators.co.uk

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Luís Luzia or Arta Raituma.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED