Amy Gough

-

Interview by Chris Alton

-

Published in January 2025

-

I first met Amy Gough about 5 years ago. We were both new to Manchester and were trying to find our people in this new city. In the intervening years, we’ve become close friends, exhibited together, and gotten to know each other’s work intimately.

For YAC, we sat down to discuss her forthcoming solo exhibition at Bankley Studios & Gallery, getting inside the head of an AI, and the digital resurrection of American singer Roy Orbison, amongst other things.

-

You Don't Have to Imagine, Single channel video, 2025

You have a solo exhibition opening at Bankley Studios & Gallery on 7th February 2025. The exhibition shares a title with your new film You Don't Have to Imagine (2025). What do you mean by that phrase?

It's got a dual meaning. Partly it's ‘you don't have to imagine’ in the sense of something coming true or something becoming real. And it's also this hyperbolic, dystopian statement; you don't have to imagine because technology will do it for you. It’s a cartoonish expression of something (a new technology for example) being just really good or really bad, filtering out nuance and realistic experience.

It also has other readings for me. A lot of my work relates to ideas around nostalgia and how changing image capturing and image generating technologies influence how we mythologise or create fantastical or idealised representations of things. It's to do with gaps in knowledge, or the gaps between artefacts or images that we fill with desires and our confirmation biases, to create an impression of something from a limited perspective - kind of a fantasy.

For a long time I’ve been thinking about experiencing things through artefacts rather than first hand. Which is something that feels really common now more than ever, because we're constantly encountering things via screens.

I am a driverless car, Single channel video, 2022

You seem to have a strong interest in emergent technologies, as well as their consequences. In I am a Driverless Car (2022) an AI that powers the car's 'driverless-ness' is the narrator. You extend a level of autonomy and a capacity for self-reflection to the AI. Could you say more about this approach and where it stems from?

I'm interested in emergent technologies, but I'm also interested in the way that they're sold to us - which kind of relates back to the title of the show. There’s the hyperbolic technological promise that's offering the next best thing, which frequently stands in stark contrast to how things actually unfold or the actual applications that these things have in the real world once they've trickled down. I like to see it from a position on the ground, which is my position I guess - just like a person using technology, a normal person. Or the experience of someone inside the small world of their individual life.

In terms of the voice, I guess it’s self reflective mostly because I’ve written it; I’m a person pretending to be a machine in order to write this script. It makes me think of the Mechanical Turk in a way. It’s hard to get inside the head of AI - partly because it usually doesn’t have one - but that speculative aspect feels important to me. It’s about the unknown of it. This kind of relates back to this idea of gaps in knowledge, and what we do with that - often we fantasise and invent. That aspect of projection is also interesting to me, both the anthropomorphising and personal projection.

It's interesting to hear that you're thinking about how emergent technologies are sold to us, because in your own films – such as Hatchling (2024) – you have little ad breaks that interrupt the narrative of that film. Where does that device come from, what's its purpose?

This often springs up by accident. I feel like the choppiness of how we experience moving image in the world filters into my work quite a lot; that flitting attention or divided attention, of always having something interrupting or popping up. There is this inevitable capitalistic aspect to it. Inevitable because that’s the backdrop that it exists within - because my work is very much informed by my surroundings both digitally and out in the world, so it all ends up being captured.

I feel like the rhetoric of advertising does seep into my work sometimes, because it's so ridiculous a lot of the time. And quite funny. If it wasn't so horrible it'd be funny. And sometimes it is funny. I don't really want there to be adverts in my work, but they creep in.

Hatchling, Single channel video, 2024

I think it makes your work quite distinctive. I was watching your new film You Don't Have to Imagine (2025) and it was almost like channel hopping or scrolling on social media. But even whilst jumping around, you manage to create connections between really eclectic references; the American singer Roy Orbison, dinosaur DNA, the reality TV series Below Deck, AI image generation. On the surface they don't seem related at all, but you tie them together. What leads you to make connections in this manner?

I think it is ingrained in the way I think. It’s ingrained in the way that everyone thinks to an extent; to make these connections between disparate things or try and weave stories out of things and make sense of information basically. But I think mine's in overdrive sometimes. It's kind of magical thinking to an extent- these leaps in logic, glossing over or creating internal systems of logic.

It's something that I reflect on and I'm aware I'm prone to sometimes, so I like to take that and lay it out and dissect it a bit - that includes thinking about how it operates in wider society, in the development of conspiracy theories for example.

When we first met you were making a range of things; paintings, zines, gig posters, music videos for bands. For the past couple of years you've been very focused on making video work. What's brought you to where you are now? What's drawn you in that direction?

I definitely am glued to video at the moment. I have been before in a way. Towards the end of my degree I was just doing video work and writing. I felt like things were clicking together in a way at that time.

I graduated and started doing loads of other things for a while. Partly to try and make my art practice financially viable, which is kind of sad in a way. But I also made a lot of music which is a big part of my practice now. Not making music to release on its own necessarily, but making soundtracks for films. That's a big part of my moving image practice; sound.

So focusing on video enables me to do that, I get to do the visual side and the audio side in one. Also it's just because I love the whole process of it. The gathering of material - which can be scanning second hand books, going through stock photos and public domain archives, reading, filming, watching documentaries, making animations. It keeps me busy. I love the editing process more than anything. I'll have an idea or themes or the beginning of something when I start shooting and collecting material, but that actual building or trajectory of the narrative; everything happens in the editing process. It's a slotting together of moments; of sound meeting audio meeting text, then something being built or interpreted from that. Nothing else hits the spot like that for me. It's really satisfying.

When I'm watching things I'm thinking about the editing or how it’s been constructed, why it's been constructed like that. My technical knowledge of cameras isn't great, but I’m thinking about what it's been filmed on and when it's been filmed. It's something I'm churning over all of the time. I love films. I love TV, shamefully *laughs*.

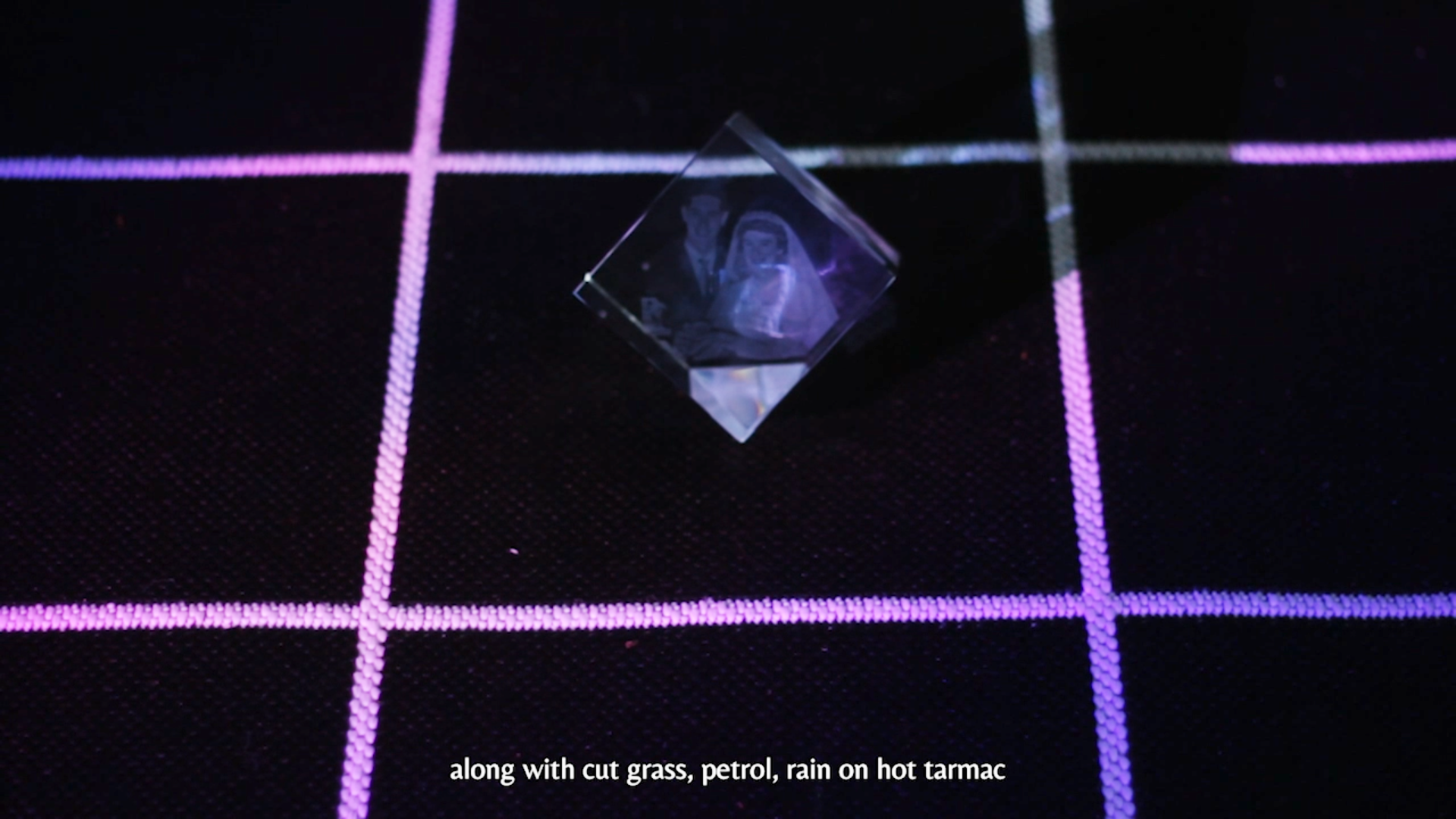

No Signal, Single channel video, 2025

No Signal, Single channel video, 2025So, you’re not receiving it passively, but trying to understand it and the decisions that underpin it. Could you say a bit more about that very attentive engagement with moving image?

A big part of it for me is the affect aspect. Something being cathartic or initiating an emotional response, simulating something. Like with horror films when you’re not in real danger, but you’re experiencing real emotions. It's a kind of exposure therapy.

But that’s why sound is so important, it transforms the visuals and sets the tone. I try to use these shifts to create a bit of emotional whiplash, or at least to orchestrate shifts in tone that reveal another layer of potential, or a different perspective. This is also kind of the audio-visual language of advertising, and cinema; these frenzied crescendos which are really carefully designed but stimulate a kind of unbridled euphoria or just generally heightened emotion.

Stunt Double, Single channel video, 2024

I’d like to end by asking about your film Stunt Double (2024), which will feature in You Don’t Have to Imagine. It’s like a short documentary. You follow two biker-gear-clad figures – the stunt doubles – who give candid answers to your unheard questions. We rarely hear from stunt doubles; what made you want to imagine their voices?

I'd been thinking about stunt doubles for a while and how weird they are. The uncanny thing of having this doppelganger and it being more uncanny somehow if it's a wholly or partly computer generated version. I'd been thinking and researching about avatars and things or people being digitally ‘resurrected’ through AI image/audio generation.

Like Roy Orbison in You Don't Have to Imagine?

Yeah and the extinct gastric brooding frog that's also in that video - but that was literal attempted resurrection not virtual. So thinking about wildlife, extinct creatures and being able to experience something that doesn't exist anymore, but in a way that's virtual and you're sort of interacting with a synthesised version of it. It's the horrible dystopian/uncanny spectre of something, but it's presented as a viable way of experiencing that thing. There’s a song on youtube that’s an AI generated Roy Orbison ‘hit’- it doesn’t measure up, but I would say that.

But with the stunt doubles, more widely, the characters are being forced to come to terms and live with changes that feel out of their control; having to adapt and create silver linings. And sometimes that's an act of having to convince yourself. At the end they talk about being freed from their onscreen bodies, and I guess I was trying to capture the sense of an idealistic realm where you're not being watched, you don't have a feeling of being watched, you're not having to see a version of your life reflected back at you via a screen- a kind of pre-apple Eden, without self awareness. I guess the irony is that we're still watching them.

-

Amy Gough (b.1992) is an artist based in Manchester. Her practice takes a speculative and sometimes humorous approach to exploring ideas around emergent technologies, nostalgia, myth, extinction and imaginative projection. Her work is influenced by contrasts and tensions between anonymous or remote, and collective in-person spaces, such as the club.

︎ @aeg.000

amygough.com

Chris Alton (b.1991) is an artist based in Manchester. His practice spans a range of media and approaches, including; socially engaged projects, video essays, textile banners, and publications. Since 2021, he's been working in collaboration with Emily Simpson on a project regarding grief, the absence of language for expressing it, and the creation of public spaces for it to be shared.

︎ @chrisalton

chrisalton.com

-

If you like this why not read our interview with John Reno Jackson.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED