John Reno Jackson

-

Interview by Daisy Gould

-

Published in December 2024

-

a house divided (wild cherry) (Left), mahogany (phoenix) (Middle), and a house divided (halcyon) (Right), 2023. Picture frame and AI generated portrait, on termite nest, charred wooden panel. (Left & Right). Oil, acrylic, charcoal, chalk, collage on canvas, burlap, on wood panel. (Middle). Courtesy the artist. © John Reno Jackson

Could you start by briefly introducing yourself? Where are you from, and how has your background shaped your artistic practice?

I am John Reno Jackson, a painter, writer, and maker from the Cayman Islands. My practice explores themes of memory, isolation, and identity, shaped by the complex histories of my homeland and the broader Caribbean.

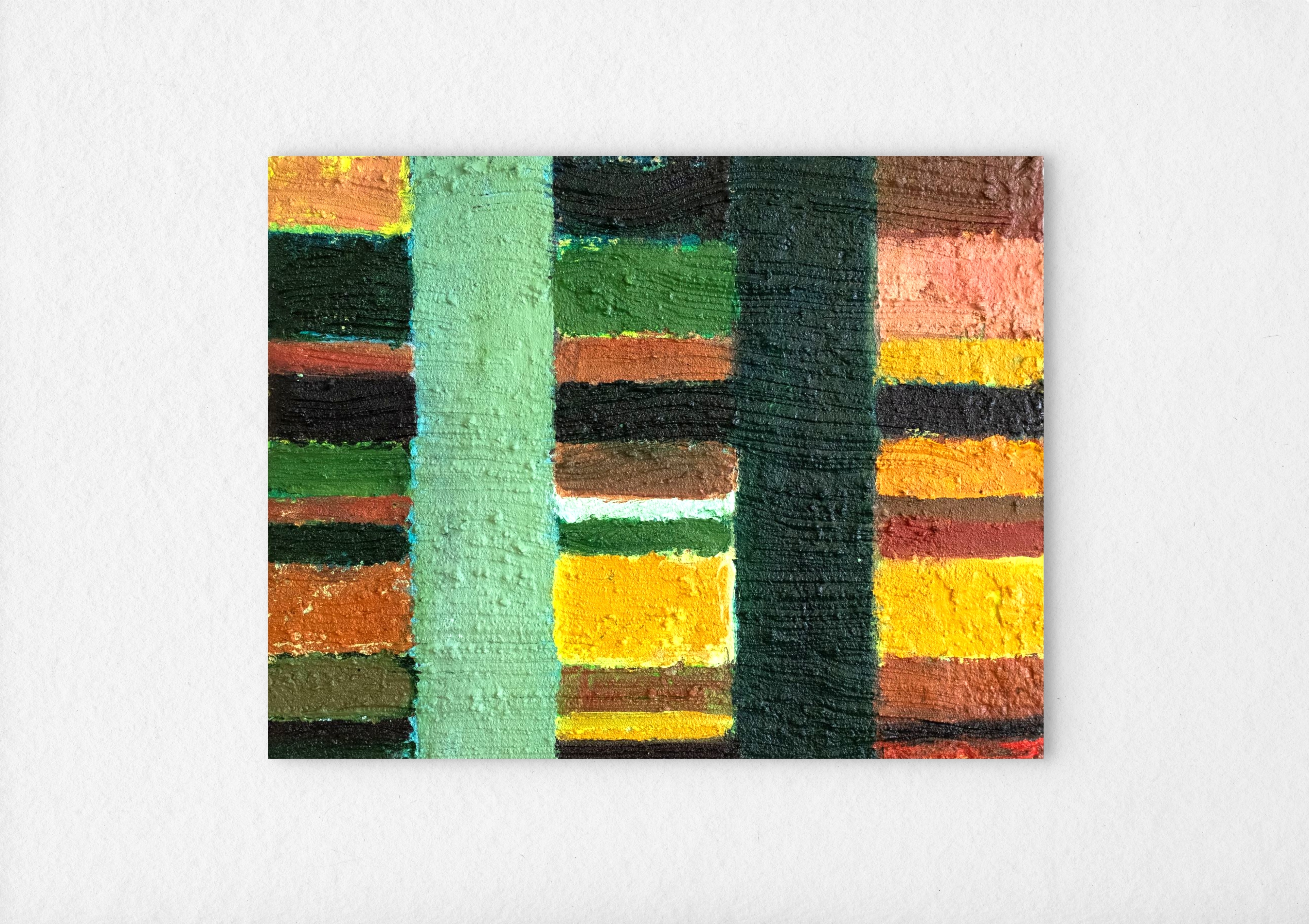

As my practice has transitioned into 2024, my focus has shifted. My new works emphasise colour and form as they appear on top of texture, exploring the intersection between these elements. Though born of my process, the textures I create are inherently variable, each with different weights, grits, or movements. When these textures interact with a design or pattern, they produce a subtle vibration, a visual hum that resonates with the viewer. This three-dimensionality, combined with the layered gestures and marks of the paint, offers a space for introspection. These paintings are built up through layers of beeswax-like paint, allowing my hand to remain visible — so as not to obscure the fact that these are paintings. My work has always maintained a connection to the body; concerning its relationship to its environment. However, in my new body of work, I aim to extend this legacy by investigating organic patterns and materials, particularly those that hold personal, cultural, and environmental significance.

boy and the nettle, 2020. Acrylic, oil, charcoal, and chalk on canvas. Courtesy the artist. © John Reno Jackson

You work across varied media—including installation, sculpture, and even elements of performance—yet painting remains central to your practice. Can you share how you initially connected with painting, and how it evolves as a core element across your work?

My practice can be labelled as interdisciplinary, but I’ve recently moved away from using that terminology. It can impose limitations, forcing me to think within an overly academic framework. Many of my strongest inspirations come from the non-academic — passing moments, objects removed from their original context, fragments of words and sayings. These found materials and observations become essential in informing my paintings. I aim to imbue my work with a sense of place, whether through motif, gesture, or allegory. My goal is to create objects that resonate beyond their surface. Painting, for me, remains a powerful way to address complex ideas through accessibility. The act of painting is something I feel people have a foundational understanding of, even if subconsciously. It offers a bridge, a way for viewers to enter the conversation, regardless of their background or level of familiarity with art. This aligns with my overarching ambition: to achieve a sense of universality in my work.

I first connected with painting during my early exploration of art, where it felt like the most direct way to express myself. A brushstroke can capture emotion, history, and even time itself. Over the years, painting has remained the foundation of my practice, even as I’ve incorporated other media like sculpture, installation, and performative elements. Painting's unique ability to anchor other disciplines provides a framework where all these elements can converge, maintaining a dialogue across forms.

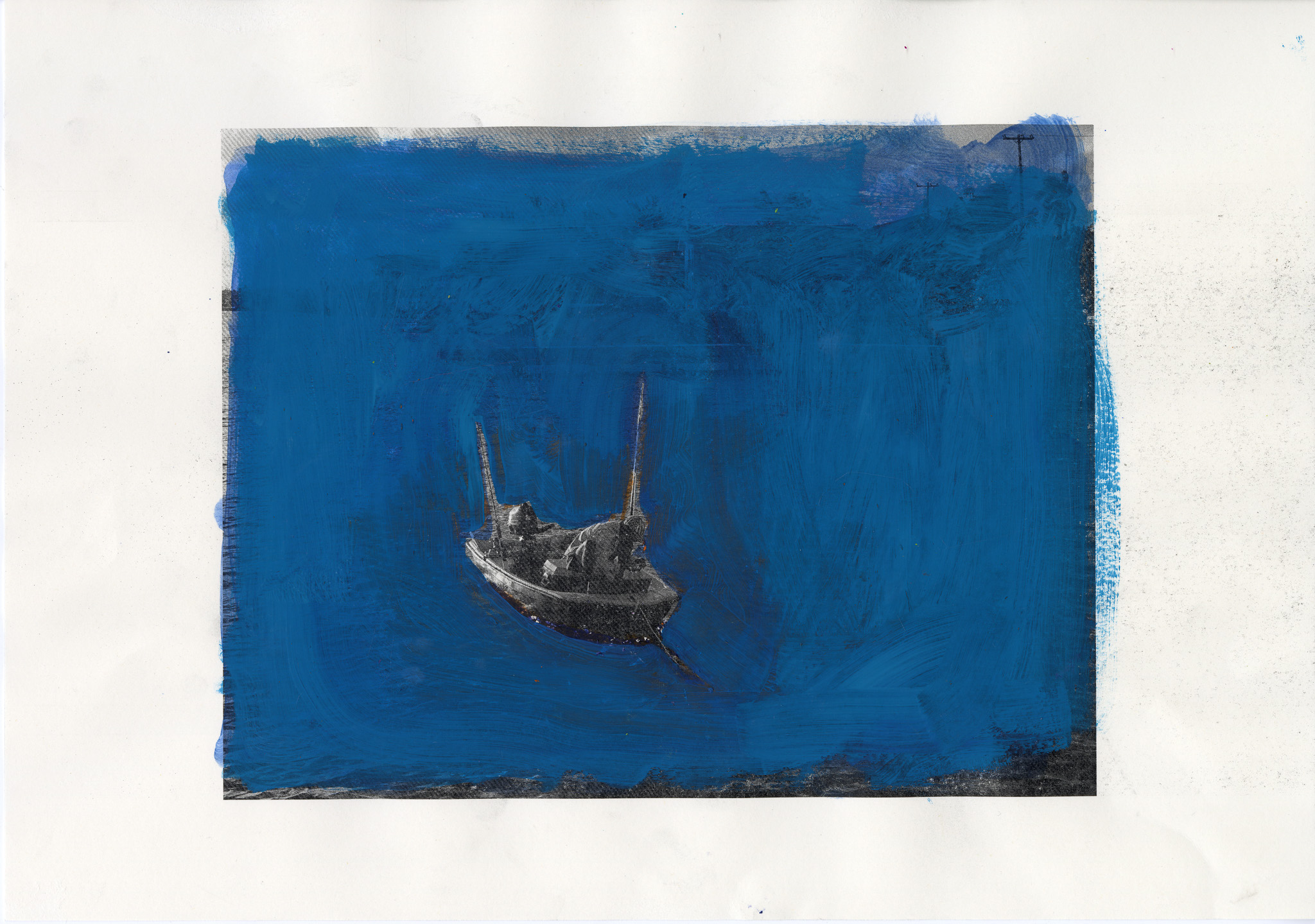

ol’ robbie, 2021 - 2023. photograph, riso print, flashe, crayon on 200gsm cartridge paper. Courtesy the artist. © John Reno Jackson

Much of your earlier work centred on abstracted figurative forms, but recently, your practice has become more process-driven and materially focused. It seems that your work for the Cayman Biennial marked a turning point, coinciding with your move to London. Could you talk about the significance of materiality in your practice and how it has shifted over time?

My earlier work was deeply internalised, focusing on my reactions to the environment around me. I explored themes like sexuality, fear and truculence in relation to nature, often through abstracted figurative forms, inspired by the works of Jennifer Packer, Willem De Kooning, and by combination Cecily Brown. These works depicted bodies intertwined with their surroundings—pushing, pulling, and melting into one another. Looking back, I’ve come to understand how much of this was rooted in human psychology at a fundamental level, reflecting our intrinsic connections and relationships to the natural world and each other.

However, moving to London marked a significant shift in my practice. I began to move away from reactionary painting, where emotion and personal narratives took centre stage, and toward an approach driven more by process and materiality. I became increasingly interested in the science and philosophical qualities of art —how paintings make us feel, how we react to them within specific contexts, and how the materiality of paint itself can evoke visceral responses. This shift was especially apparent in the work I created for the 3rd Cayman Islands Biennial, “Conversations with the Past - In the Present Tense”. The works titled, mahogany (phoenix) and house divided (wild cherry)/(halcyon), were a triptych depicting a transition between states of identity, drawing inspiration from the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who defined identity not only as a matter of ‘being’ but of ‘becoming’. This work acted as a bridge between these two phases of my practice and helped develop my current material relationship with painting.

Materiality has since become a central focus for me. I’m fascinated by the physical qualities of paint—its texture, weight, and movement—and how these elements can communicate without relying on direct references or explanations. My goal is to push the materiality of paint to its limits, creating a sensory experience for the viewer that transcends narrative or figuration. This alludes to a thought brought up by the artist, Jack Whitten. His concept is about moving from A to Z with no roadmap, no points of reference—just the pure, unfiltered act of making. To me, this is true liberation, allowing the process to dictate the outcome and inviting the viewer to respond on an instinctive level.

mydas study, 2024. acrylic, sandstone, synthetic distemper and synthetic wax on canvas. Courtesy the artist and TERN Gallery. © John Reno Jackson

Your compositions have become increasingly abstract, though they retain a strong sense of deliberate structure. Despite the simplicity, I know you approach composition thoughtfully, with attention to the "hidden figure" within your work. Could you describe your compositional process and the ways your research informs it?

This is a great question. While my painting-based work may appear simplified on the surface, it serves a much deeper purpose: to express a language that has yet to be fully realised. My compositional process is deeply informed by ongoing research into indigenous practices within the Caribbean region, including those of the Guna people of Panama, as well as the Taíno and Kalinago cultures. I am very interested in the fundamental reasons humans began creating in the first place.

The Cayman Islands, my home, is a relatively young country in terms of stable human habitation or settlement—only around 300 years old. Unlike many older nations, we have yet to fully define our heritage or contemporary culture through art-making. My work seeks to address this gap, contributing to the foundation for a unique cultural language. I approach composition thoughtfully, embedding a "hidden figure" within the structure of my work. This figure isn’t always literal but often takes the form of a motif, a gesture, or a rhythm derived from my surroundings.

I draw inspiration from the environment around me—its flora, fauna, and landscapes, from the swamps and sea to the vibrant birds, thatch bags, and turtles that are central to our heritage. These elements hold layers of meaning, and I aim to translate them into forms that resonate with a contemporary audience.

amazona, 2024. acrylic, sandstone, synthetic distemper and synthetic wax on canvas. Courtesy the artist and TERN Gallery. © John Reno Jackson

Speaking of the gesture, we’ve discussed the idea of the "allegorical gesture" in your work, and the ways you access this. What role does gesture play in the materials you select and how do you use them?

Yes, allegorical gesture is one of my favourite terms (something you gave to me in one of our previous conversations) — it has been key to bridging the gap between the figure and the abstract in my work. My earlier paintings were rooted in the figural, but my recent works seek to explore both the figure and the abstract simultaneously, treating them as separate yet interwoven. By using the concept of allegorical gesture—a gesture that serves as a narrative element tied to a history or idea, rather than an overt representation—I’m able to present the histories of my people through gestural mark-making.

This process begins in the early stages of the painting. I layer organic marks and patinas that connect to stories, traditions, or memories. The materials I use play a crucial role in this. For instance, the use of textures like the thatch palm or patterns inspired by traditional weaving, provide a tactile link to the Cayman Islands’ cultural and natural history. Gesture, for me, is more than a physical act—it’s a way of connecting with the past while creating space for something new. It allows the paintings to hold a duality: the marks are abstract, yet they carry the weight of stories that resonate with the environment and people I represent.

lee miller’s picnic (parrot), 2024. acrylic, sandstone, synthetic distemper and synthetic wax on canvas. Courtesy the artist and TERN Gallery. © John Reno Jackson

Memory, both personal and collective, is a recurring theme in your work. How does being from the Cayman Islands, along with your research into Caribbean history and regional memory, influence the materials and methods you choose?

Memory is at the core of my practice—specifically, how we process and perceive memories, particularly those that feel elusive or inaccessible. In the Caribbean, much of our history has been erased or left undocumented. This is an unfortunate reflection of the region’s transient past, where so much has slipped away, lost to the annals of time. This chronicle inspires my work: an attempt to replace, replicate, or construct memories that feel simultaneously immemorial and contemporary, interweaving the past and present into a pluralistic space of emergence.

This intersection—the collision of past and present—resonates with Édouard Glissant’s Archipelagic theory. It exists between science and philosophy, offering a framework to explore what we’ve intuitively known but struggled to articulate, constrained by colonial legacies that shape our understanding of history and identity. While change is slow, it is inevitable. Over time, these shifts allow us to rewrite future histories, building narratives that honour what was lost and illuminate what could be.

mahogani two (pod), 2024. Acrylic, sandstone, synthetic distemper and synthetic wax on canvas. Courtesy the artist and TERN Gallery, Nassau. © John Reno Jackson

Now that you’re based in London, does the concept of place—along with the dynamics of distance and proximity—affect your process, particularly in terms of ecology and environment?

Not necessarily, but in actuality, it has. I don’t feel pressured by the environment here—my work has nothing to do with London. Even though it feels like I’ve “returned to the motherland,” I don’t have a direct connection to it. What I do feel is a stronger drive to connect back to my own country. Coming here has made me realise how unique it was to grow up in the Caribbean. People here tend to overlook my experience as “other,” but I believe it’s just as valid as anyone else’s. The distance has made me reflect deeply on the things I miss—things from memory that don’t exist here: The wind rustling through the palm trees at night, the sound of sea turtles exhaling at the ocean's surface—everything moves at a slower, more deliberate pace. I’ve been examining every little detail, cherishing them, and translating them into artwork. In a way, the pieces I create now are like shrines or altars to my memories, a way of preserving and honouring what feels so integral to me.

That said, my local environment back home is crucial. It shaped my impression of the world. My greatest fear is that one day, due to climate change, it will no longer be there for my children to experience. I already know that the island that I grew up with isn’t the same as the one that exists today. My parents often express the same fear about culture. They were born in the 1960s, the last Caymanian generation to experience the country before globalisation transformed it into the tax haven/financial centre it’s now known as. Everything they’ve known has changed dramatically.

These concerns, a return to a localised focus, are central to my work. I look to colours, patterns, and materials to reconnect with and ground my country in its cultural roots. As we continue to develop, we risk losing our identity. My job as an artist is to protect that identity or, at the very least, contribute to the history of what it was. The works I create don’t need to have immediate meaning. Meaning can emerge over time. What matters to me is that they serve as a record, a way of preserving what it means to call the Cayman Islands home.

Portrait - Self Portrait in Studio, 2024.

What are you working on now and what are you most excited about in the future?

Right now, I’m focused on completing my Masters in Painting at the Royal College of Art. Once I finish, I’m excited to return home and share everything I’ve learned over the past few years with my community. I hope to take up a research role locally, either with the National Gallery of the Cayman Islands (NGCI) or the Cayman National Cultural Foundation (CNCF) as I start preparing for my PhD studies.

In addition, I’m currently writing a book about Cayman titled Lest We Forget, which I plan to launch in the coming year. I also have some exciting projects lined up with TERN Gallery in the Bahamas. This is significant because, in my unbiased opinion, TERN is producing some of the highest-quality shows in the region. Their work is raising the bar for Caribbean art and demonstrating that our region is emerging as a respected force on the global art stage.

-

︎ @johnreno

johnrenojackson.com

︎ @daisymgould

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Gwen Evans

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED