Cherie Li

-

Interview by Aoife Donnellan

-

Published in February 2025

-

Visual artist and Anthropologist Cherie Li uses ethnographic techniques in her practice to interrogate relationships between intimacy and place. Li’s work features micro-autoethnographic studies, interrogating developments in anthropological methods through her multi-modal approach, to explore non-textual and embodied forms of communication. The materiality of her work shifts from paper to the wall, into music and film, capturing life's brevity and liminal nature. Through transcripts of conversations with family, material recreations of walks through Hong Kong, and exhibitions created in her apartment, Li’s practice examines care and joy as quiet companions who get in through the cracks.

-

Your work adopts a various approach to capturing embodiment and non-textual forms of communication. In the sculptural work walking in Hong Kong (2018), you collect and display materials that you have touched as you traversed the city, capturing tactile moments of connection to material. Could you expand on your approach to the visual rendering of embodied knowledge?

A question I often ask in my practice, which can facilitate making, is how can I condense the activities of time and touch into something visible and material as a means of capturing presence and encounter. In walking in Hong Kong, I rely on collecting traces of my movements through the city in the form of my footsteps imprinted on aluminium beneath my shoes and paint peeling off building walls. Traces became an important visual and material feature of my work. I thought of traces as being formed at the precise point where things touch and converge, a tangible form of intangible things – the residue of actions and effects, occurrences that are fleeting and time-based. One summer in 2018, two weeks before I was due to leave Beijing, I made it a personal project to do ten covert things in and around my family home, such as filling in all the hairline cracks in our walls and planting a row of ‘humble plant’ (mimosa pudica) seeds along the edge of our garden. The project grew out of the desire to do something that could still be ‘happening’ even after I’d left, extending my presence long past its due date; essentially leaving traces of myself behind. More than that, it was my attempt to exist and act through materials and objects. It speaks to non-language-based forms of keeping in touch with loved ones and maintaining connection, presence, and care; as you articulate, a practice of non-textual forms of communication. I’ve been able to explore these ideas further in an ethnographic research project, where I look at the role of objects in how people sustain connection and enact care towards each other in long-distance relationships. What came out of my fieldwork and interviews were case studies of how objects make visible and sensible the invisible, immaterial threads that tie people together.

in the burned house I am eating breakfast, handmade paper embedded with food ingredients, 2018. Photographed by Natasha Karam. Exhibited at St. Margaret’s House, Edinburgh.

The materials that feature in your work are often domestic. In your work in the burned house i am eating breakfast (2018), you produced paper embedded with rice, pasta, eggshells, sunflower and sesame seeds, alongside which you wrote poems on emotional inheritance and family. How do you approach material considerations?

For in the burned house I am eating breakfast, the departure point was my own lived experience,as with much of my work, and I chose to work with materials that are evocative of my relationship to family. I come from a family of chefs; my grandparents started a family-run restaurant in Beijing that has been inherited by my parents, and I spent my childhood growing up in the restaurant kitchen. In our family, food is a shared language of care we communicate in; an offering of one’s time, effort, attention, and commitment to another’s good life. My choice to work with food ingredients also responds to the intimacy of food and eating, which involves allowing something into our bodies. I saw intuitive parallels between this and the way my family relations inextricably compose my being; how others are a part of me. There was also the sensorial quality of food and the way it affects the body viscerally – how it activates the senses of taste, smell, touch – that make it an evocative site of memory and imagination. Domestic materials and spaces have often featured in my work because they’ve been meaningful sites for caring relationships in my life. Of course, domestic spaces are also contentious spaces, they can be sites of danger and trouble as well as safety and comfort. In revisiting these works, I see room for me to be more critical of, or clarify, the specificity of my position and experience.

this is just to say, so sweet, site-specific installation with found and altered materials, 2019. Photographed by Natasha Karam. Exhibited at Degree Show, Edinburgh College of Art.

As both a trained anthropologist and visual artist, your methods investigate ways of knowing and understanding the world around you. How does your background in anthropology inform your practice? Is there a generative intersection between visual art and anthropology?

I initially gravitated towards the field of anthropology because of the kind of arts practice I found engaging and exciting. Relational aesthetics and social practice have been influential for me; I was drawn to artists who work with time, change, and social interaction as material, whose outputs exist as moments or experiences of sociality. There’s a lot of insightful discussion on the movement of art and anthropology towards each other, and rich work being produced at the intersection. They are two disciplines that find familiar concepts and shared projects in each other, such as (in broad terms) the project of making the familiar strange, of closely observing and interrogating the mundane. My visual artwork has always concentrated on details of everyday living and collecting textured documentation of them in order to make sense of them. Now equipped with training in anthropology, I realise I was engaging in ethnographic techniques without identifying them as such; anthropology has given me new frameworks with which to view my artistic method. I use observations, fieldnotes (audio recordings, conversations, transcripts), photography, archives, and interviews as both research and presentation methods in my practice. You previously described my work as featuring auto-ethnographic studies, which resonates with me. Anthropological literature also continues to inform my thinking and ideas, particularly literature on care and the anthropology of art.

as long as you exist i’m happy, screen captures of video documentation of performance, 2017. Exhibited at 104, Edinburgh College of Art.

Does your work leading creative learning through play activities at the Young V&A inform your visual arts practice?

I’d like for it to, and I hope that it does. The process of leading creative learning-through-play with young people and my own art practice share many of the same elements: playfulness, relying on intuition and observation, being responsive, and an open-endedness to what is generated. But so far in my independent practice, this process has been more individual and contained. With the creative learning-through-play activity that I lead, we often depart from a loose prompt or invitation to participants, and how that unfolds is a special alchemy. It is wholly dependent on the factors that form a moment – who participates, the energy we are each bringing at that moment on that day, what is happening around us. The playing and creating happen in the interaction between me and others and the space we’re in. Though I don’t know what it will look like yet, I hope to make this kind of togetherness, collaboration, and participation a more prominent part of my visual arts practice. In a way, the participatory creative activity I deliver is akin to the social practice art I was always drawn to. Linking back to your question about art and anthropology, in my work as a facilitator one of the most important considerations is how to engage with communities in a meaningful and responsible way, which is a question that anthropology confronts constantly. I’d also like to bring more joy into my practice! Creative learning through play emphasises the value of joyfulness, as no small or trivial matter, but a powerful catalyst for healing, connection, and community.

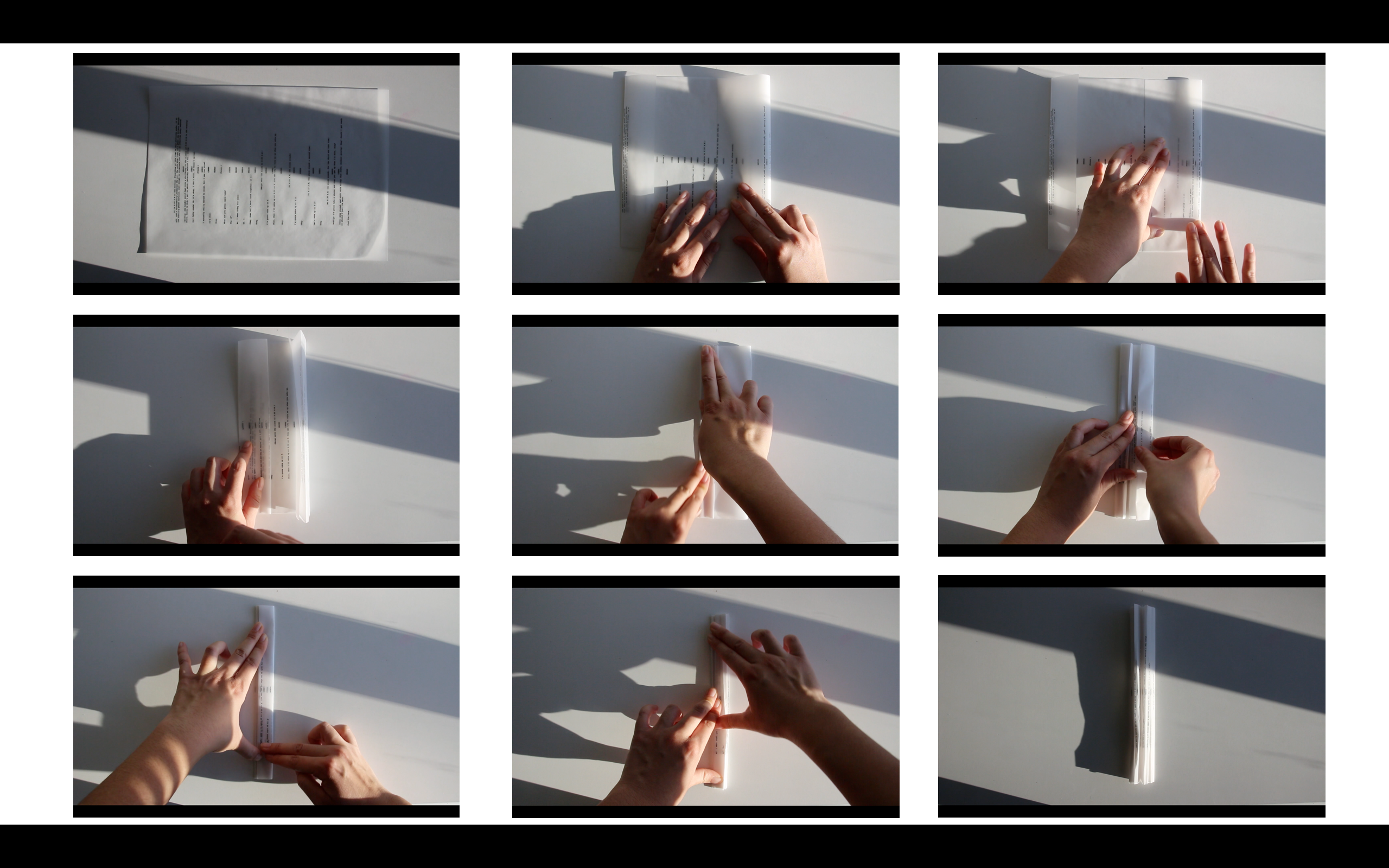

as long as you exist i’m happy, tracing paper puppets, 2017. Photographed by Cherie Li.

-

︎ @cherie_yingli

cherieli.cargo.site

︎ @aoife_donnellan_

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Amy Gough.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED