Gaspar Willmann

Interview by Duncan Poulton

-

Published in January 2023

-

Hi Gaspar! It’s great to be able to find out about your work in more depth, having been a fan for years (from afar, online of course!). I wonder if you could begin by speaking about how you came to be making the kind of work you’ve been making recently? Can you trace the origins of your current practice?

Hello Duncan! As you can imagine it is difficult to locate a practice through a single explanation. The paths that led me to art are multiple, just like they were for you. Regarding the forms and ideas I am specifically producing now, I would say that they are very much linked to the question of smoothness, sleekness and reflection. It was an obsession for a long time, but one that I have been trying to question in the last 4 years. This fascination probably comes from my encounter with a generation of artists and their works, revolving around The Berlin Biennale by DIS in 2016: Artie Vierkant, Amalia Ulman, Ed Atkins, etc. The date makes sense since it is also a time when I was still studying, when in general my art practice was under construction.

My work is among other things the result of these fascinations and the desire to deconstruct them with a more reasoned study of acceleration, affects, and new technologies through the prism of images.

Exhibition view, Fresh Widower at Friche la Belle de Mai, Marseille (2021)

I think we share an interest in the ugliness of the internet, or the imperfections of the amateur image. Much of both of our recent work feels very nocturnal. Elements of your recent paintings such as the cigarettes, plastic cups and bottles remind me of teenage house party uploads, where our generation didn’t think twice about dumping unedited albums of personal photos to platforms like Facebook and Flickr. You can almost feel the stickiness of the room the photos were taken in. Now those images exist somewhere forever in cloud storage, way beyond individual accounts being deleted. There’s something quite melancholic about this archive of our formative years being so abundant, and yet so unprecious. I wonder if you could speak about why you’re so drawn to this kind of ‘throwaway’ digital image?

In both of our works there is a kind of admission that it is not possible to escape common references, whether they are the adolescent ones: our discovery of the internet in the mid 2000s, or even more buried ones, like a romantic heritage in my case.

The motif of ruins, for example, is omnipresent, both physically in certain exhibition spaces, as well as metaphorically. For me It is the perfect exercise to transform our own waste (digital, or from our ordinary consumption) - which confronts us with our own nothingness - into ruins, which suggest much more a form of rebirth after a catastrophe or destruction. It’s the idea that grass and flowers grow back in the rubble, which can be found among painters like Hubert Robert, or any fiction about a nuclear disaster, etc. On the internet, waste is in fact forgotten things. These images are buried, may lose their quality but will never really disappear. Giving them a second visibility allows us to reflect on why they were put aside, in favour of something "new". It is obviously a virtual space that allows us to simulate and think about other worlds.

There’s an element of déjà vu to your work. The images that make up your works are familiar and something we might have photographed ourselves, and also there are repetitions (or clones) within individual works. You sometimes make more than one version of the same painting. What interests you about this process of remaking and the ‘already seen’? And could you share a bit about the digital element of your process, the sketches you make as precursors to the paintings? Do you show the digital sketches?

In my work we often find a romantic quest for the «perfect» image. The image is revealed through very vaporous, cloudy elements, in the manner of a waking dream that will create this sensation of déjà vu. For my series of paintings JUMAP (JUMAP is a French acronym for “just focusing on the most beautiful images of my life”) I will multiply the versions and the exports of the photomontages, sometimes hundreds of them, before selecting "the right one". By repeating the same task, one ends up improving its occurrences, or at least taking them somewhere else. Just one command that cancels one task on the computer allows me, in 5 minutes, to repeat what a "classic" painter would take a week to develop. All the missed sketches are not shown to the public, but they can be used later in videoworks as a starting point for scenery or other installations: everything is reused at one point.

Therefore, if the painting exists in several pieces, it is either to intensify this anxiety-inducing sensation of perfection and of the commonplace, or on the contrary, to put forward the errors and clumsy gestures of the painting, through a game of comparison. By using the first results of Google Image, I make sure that the viewer reaches this state of surprise; this impression of having already come across the same figurative elements. It is a vocabulary of forms that belongs to everyone, but interpreted by an individual.

JUMAP (2048) ink and oil on linen, 40x27,5cm (2020)

Following the digital painting, you then re-render the image in painting on canvas or linen. You’re painting from pixels, so there’s this analogue to digital to analogue shift going on, what I’ve heard artist Mark Leckey refer to as ‘flip-flapping’. Here’s a big question for you: why painting? Why go to the labour and effort of recreating the image? How do you see these works in relation to the infinite flow of online images from which they originate? In relation to this, I’d also like to hear about time in your making process. You work quickly with your digital materials and then go through this more time intensive process of painting from this. How does your perception of these digital images shift during this process? Do you ever work from life or only photography?

I have always had a love-hate relationship with painting. I consider that there is a form of useless exhaustion when I realise the sheer diversity and quantity of already existing forms online, especially when it comes to figurative painting. What's the point of re-making them, of going through all that labour, as you say? It's almost an “ecological logic” of the gaze.

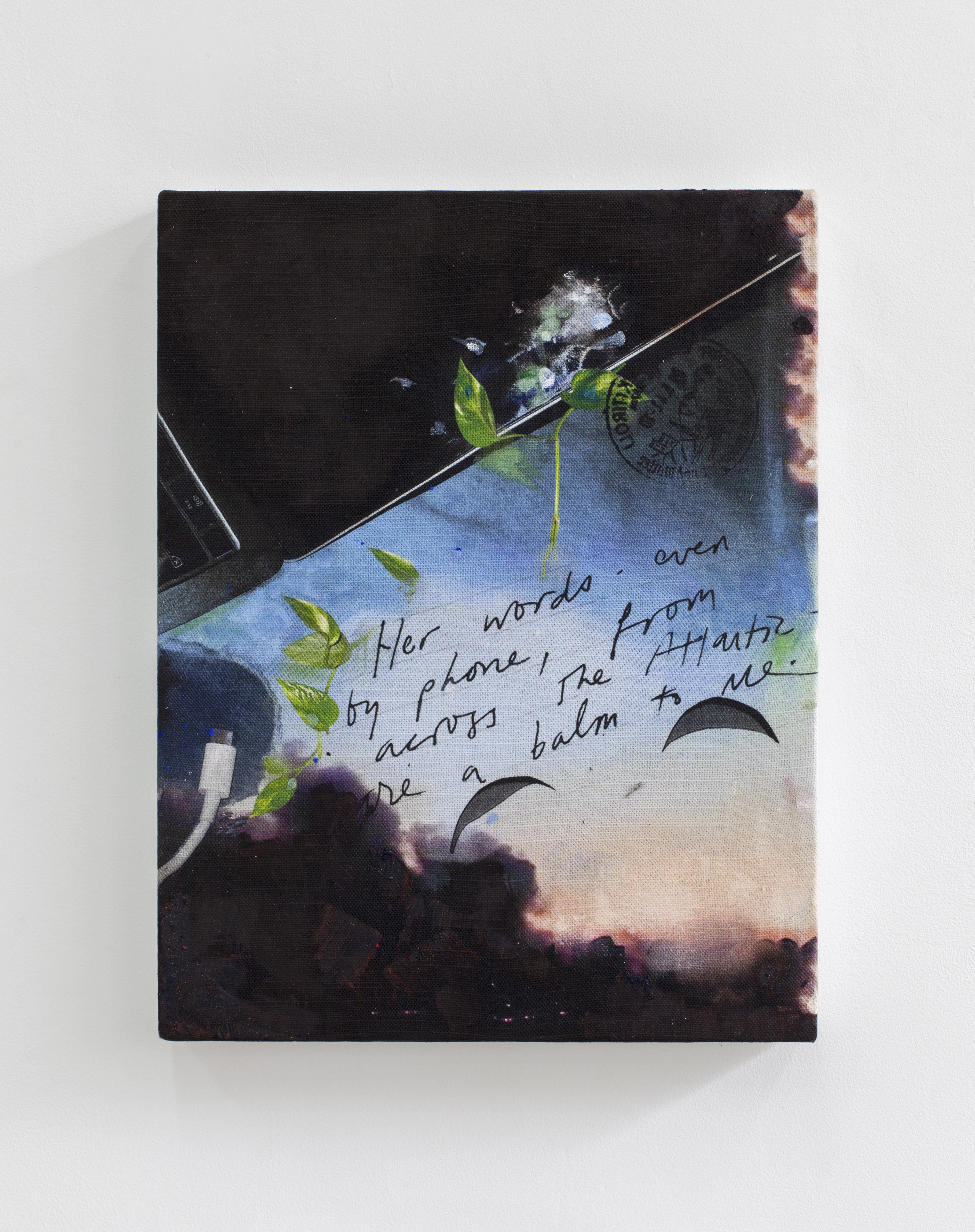

JUMAP (Her words) ink and oil on linen, 40x28cm (2021)

However, there is a very physical dimension to painting that I really appreciate. My body, until then prostrated in front of my computer, is suddenly put to work on an image bigger than me. It is a restorative moment after a full day of sitting in the same position, spending less than a second on each image. Time becomes a central element: I often say that painting is actually the only medium I have found in order to spend at least a week with the same image. In this way, this forced and reasoned taking of time allows me to seek appeasement and to leave the "feed". Little by little, I start to rediscover parts of the image that were not obvious at the beginning. I will look for efficiency in Photoshop and in the printing process so as to later be able to concentrate on more futile things when I am painting, which makes things much more sensitive in my opinion.

We’ve spoken about French philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the ‘Simulacra’–a copy without an original–before, in relation to how we think about our work and the contemporary mode of vision. What kind of things were you reading and watching when you were studying and forming the foundations of your practice?

I often quote the writings of Seth Price or Hito Steyerl, which in my opinion are fundamental in understanding our relationship to images in the 21st century, in this sort of endless loop of feelings, whose reproductions become the main subject, almost a character.

In the same way, I remember writings and podcasts by Artie Vierkant, who has a very Baudrillard way of considering that representation can exist without reference to the original. The development of my practice has led me to go against these conceptual ideas as well, especially Vierkant's very "post-internet" plastic language. My favourite texts are often from artists, and this is what makes art research special. A very personal way and path to study things. I have always put on the same level, in a sort of horizontal form, as many videos, exhibitions, poetry, essays as possible; they are all equally founding experiences in their own way.

What inspires you outside of art? For my recent solo show Factory Reset I made a playlist of music that resonated with the work and that I was listening to whilst making it. What have you been listening to lately? What would a soundtrack to your practice sound like?

I really like trance, hardcore, especially the French scene which can sometimes seem quite dumb and cheesy. While remaining a music amateur, I sometimes make parallels with my practice. The idea for example that in gabber there isn’t a real worry about sampling anymore, but simply "stealing" things to mix in very recognisable kicks. It's a radical efficiency that I find in my relationship with images. I've been listening to a lot of downtempo, lento violento lately; within which we find this need to slow down, to the point of exhaustion while all the while keeping a form of violence. It may seem unbearable but when I'm in the studio and working with music, I sometimes slow down a whole playlist by 50% using the youtube speed tool. For example, the very kitschy figure of Gigi D'Agostino fascinates me: in that extreme romanticisation of anthems and melodies of the 20th century, but played for the era we live in.

Exhibition view, Fondation Fiminco, Romainville (2022)

Someone pointed out to me that nearly every work of mine features a portrait, be it a toy phone or a handmade emoji. It’s funny how, as an artist, no matter the materials you’re working with, you’re subconsciously drawn to certain genres. Recently I was in Frankfurt at the Staedel Museum and saw some mind-blowing still life paintings by 17th century Flemish artists like Cornelis de Heem. Your image-world is populated by flowers, food, drink and technological detritus, set in abstracted domestic space–we could likely draw a line between your work and this Nature Morte tradition. Is this a conscious decision for you, and do think about yourself in this lineage of the still life tradition or do you revolt against this comparison?

The comparison makes sense for my JUMAP series, although the whole of my work - which includes videos, texts and other series of images - is not about this idea.

From the beginning it was a conceptual interpretation of the English or German term "still life", "stillleben" as a tool to stop the flow of images (curiously French word "nature morte" is quite different and can be translated as "non-living things"). It's also a non-subject for me: it's so omnipresent (in art history, advertising, etc.) that it becomes invisible, and allows me to focus on the way the image is made and comes to us rather than getting lost in looking for a subject or meaning. It is not a matter of depoliticizing a subject, but rather of directing a gaze.

The work of 17th century Flemish artists are of course fascinating, especially in the compositional standards of the image, which are almost too much; like those sunsets that you sometimes see in the background on the left side, as a rise or ending opulence. But I would say that my heritage of still life is not only one where you have to represent the most richness and information in the same place. At that time it’s also the rise of capitalism and colonialism, with ships from all over the world bringing goods in Europe: the representation of these things is not innocent. In my case it’s mainly a moment of great banality, of intimate boredom too, far from an angsty consumerism. That’s why you often see cigarettes, drinks or sunsets from my personal library of photography as well. My favourites would be the still lifes from Christophe Yvoré or Kurt Schwitters who integrate elements of their personal life despite the effective simplicity of the subject.

Let’s talk about the future. As we’ve said, in our lifetime we’ve shifted from the image being a semi-rare thing, with photography being an expensive and professionalised field, through to the democratisation of the technology of production, and then this exponential explosion of content production and sharing with the internet and smartphones. And then in 2022 we have mass access to sophisticated AI image making platforms. What do you think this image-world will be like in 2030? How do you think artists will exist in and respond to this environment?

I think that the role of artists is going to be more and more a matter of context. Artists' works are becoming more and more similar: not only because there is a greater diffusion of works and things are naturally compared with each other, but also because I have the impression that the sources are not diversified, and that the idea of "novelty" is often a lure: it's previous ideas, aesthetics that are often re-masked.

What becomes important is really to assume a position at a given moment. The image takes on its importance in the place where it is shown, and by the way the artist presents it: publishing a painting on Instagram or hanging it in a gallery is not the same thing: there are so many different implications between the two processes, even if in fact it is the same painting.

But I am especially afraid that by 2030, visual culture will be too rational. I am afraid of the effectiveness of the tools put in place, such as eye-tracking, and the collection of data on our ways of looking at things. In a recent project (https://exoexo.xyz/show/yeuxclos.html), I mentioned all these tools that aim to produce images optimised for what is expected of them, and no longer for aesthetic questions. Choosing the colour green for a logo, putting a child smiling on the centre of an image is not a coincidence anymore. These images thus reconstruct the entire visual landscape, right down to the physical spaces. That's why, as long as artists show things that are failed, shaky, provocative, and as long as we can take the time to look at them, I'm not worried.

Exhibition view, « Dans des yeux clos, il n’entre pas de mouche » ExoExo, Paris (2022)

We met online through Instagram. Before this interview we had a Zoom call and you mentioned that you felt an affinity with a lot of work coming out of the UK and other parts of Europe. What would you say about the art scene in Paris and France at large? Do you think digital artists can survive with purely digital networks distributed across the globe?

Although things are evolving, I have always felt alone developing my digital practice, whether in Paris, where I work, or in Lyon, where I studied. I think that French institutions are very shy when it comes to acquiring digital protocols, websites, etc. in their collections. It's a double-edged sword, because many French artists, and I'm probably one of them, are leaving aside a 100% digital practice to focus on how to physically present these works in an exhibition space, because that's what is expected of an artist today. But it becomes a new way of doing and thinking too. I was reassured to find people thinking about the same things online and during a part of my studies in Hamburg. It's the principle of community, and it feels good to see that social networks can still work for the way they were intended. The increase of off-site exhibitions lately is a step in that direction. I would love to see major exhibitions conceived for an online and afar situation at the same time.

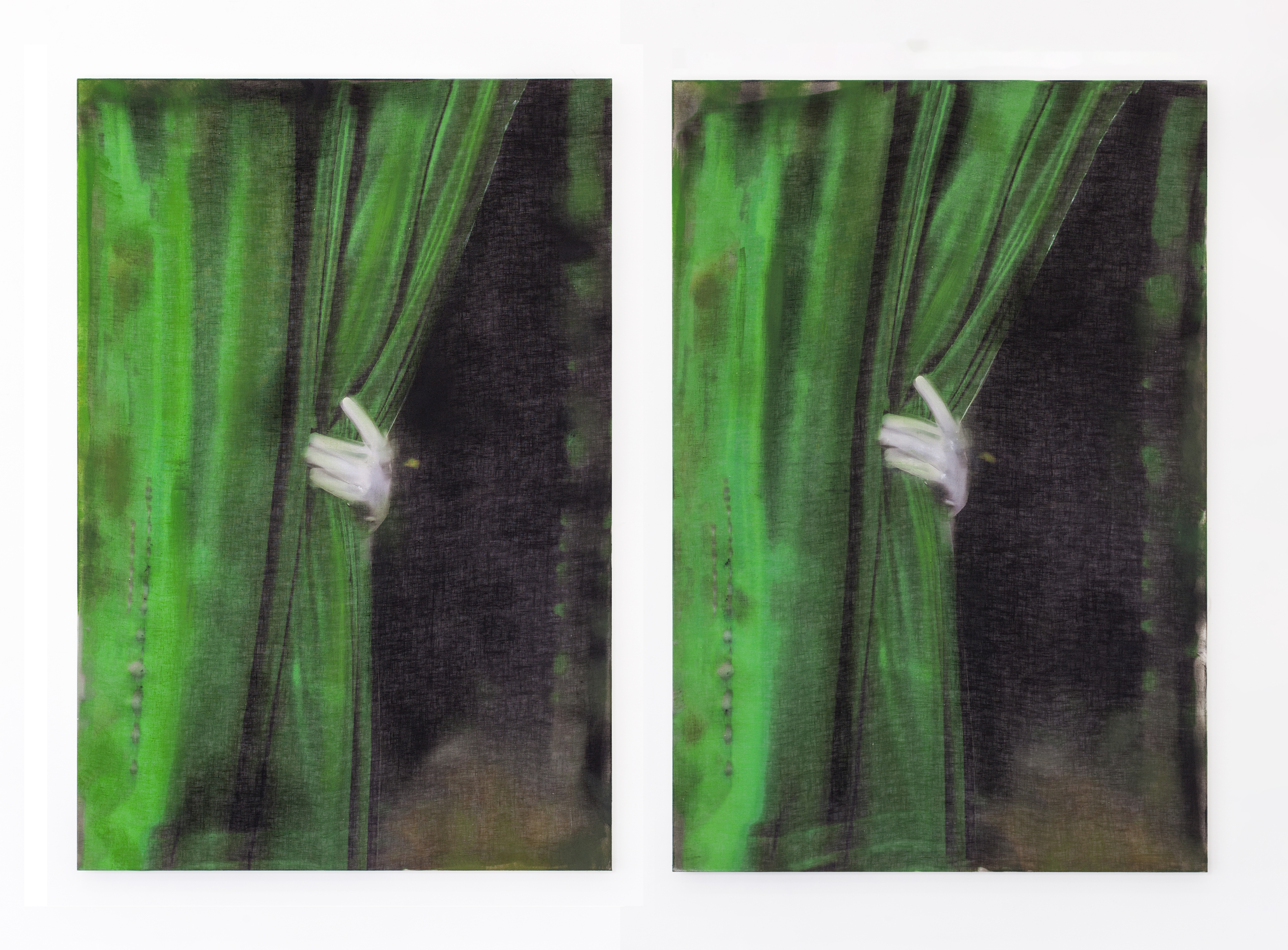

6038 (2) & a few mistakes, ink and oil on linen, 121 x 82 cm (2022)

6038 (1) & a few mistakes, 2022 ink and oil on linen, 121 x 82 cm (2022)

-

gasparwillmann.com/

︎ @gasparwillmann

duncanpoulton.com/

︎ @duncpoulton

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Natasha Tontey.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED