Hannah Hornby & Simone Marconi

-

Published in January 2026

-

Since meeting Simone Marconi I have always been intrigued by our shared interest of writing in our practices; the overlaps and the differences. In our BA together we co-curated a space for Spike Open Studios, Damnatio Memoriae, where we considered the fragility of memory, erasing histories and altered time. Sculptures, paintings and sound works littered the space acting as fragments of events which had already occurred or maybe were yet to happen. Recently I invited Simone to a conversation about our practices over a year since this project, to explore the possibly shared but also disparate approaches and perspectives we may have, in hopes to continue learning and reflecting on my own practice but also my peers. For me it is important my work doesn’t become a solitary practice and instead is something which is formed and shaped around collaborative discussions and knowledge exchange.

We began our conversation by thinking about our current thoughts and interests which are leading our practices at present?

-

Simone Marconi: I just wanted to say I am really excited to start this conversation, as I believe I know your practice quite well, but I'm also super keen to know more. Even though our research is very different in form, we share many crossovers and shared experiences that have definitely influenced us both as artists.

As an artist and writer, I am currently analysing and exploring how discomfort is often employed to construct fictitious narratives and chronicles. I use words and their fixed and momentary connotations to speculate on dialectical confusion and its active nature within history. The written dimension interplays with the slippery and ephemeral nature of the image and its materiality - materiality that, like time, is in a constant state of flux. Language, as well as materials, go through a sort of alchemical process where words lose and get back their meaning continuously, and media and materials are constantly shifting, deceiving the audience. I want to walk the worn tightrope between tangible and fictional, inviting the audience to delve into the emotional complexities of our times. I blend instinctive and poetic approaches to assemble new life into natural and manmade discarded materials. Even soft and malleable materials are charged with ongoing tension, and the audience can both read the work as ready to be activated or as leftovers of a sad-ended story.

At the moment, I am building hostile, fragile and precarious habitats and environments for text-based work to be experienced and absorbed by an audience in the first person. These archetypes set up spaces between the physical and the conceptual; metaphors and allegories for resistance and survival. In a way, writing, whether recorded, inscribed, sculpted, or projected within the work, allows me to build worlds that are not about knowing, understanding, or controlling everything. Realms that undo, unworld, take apart, break down hierarchies.

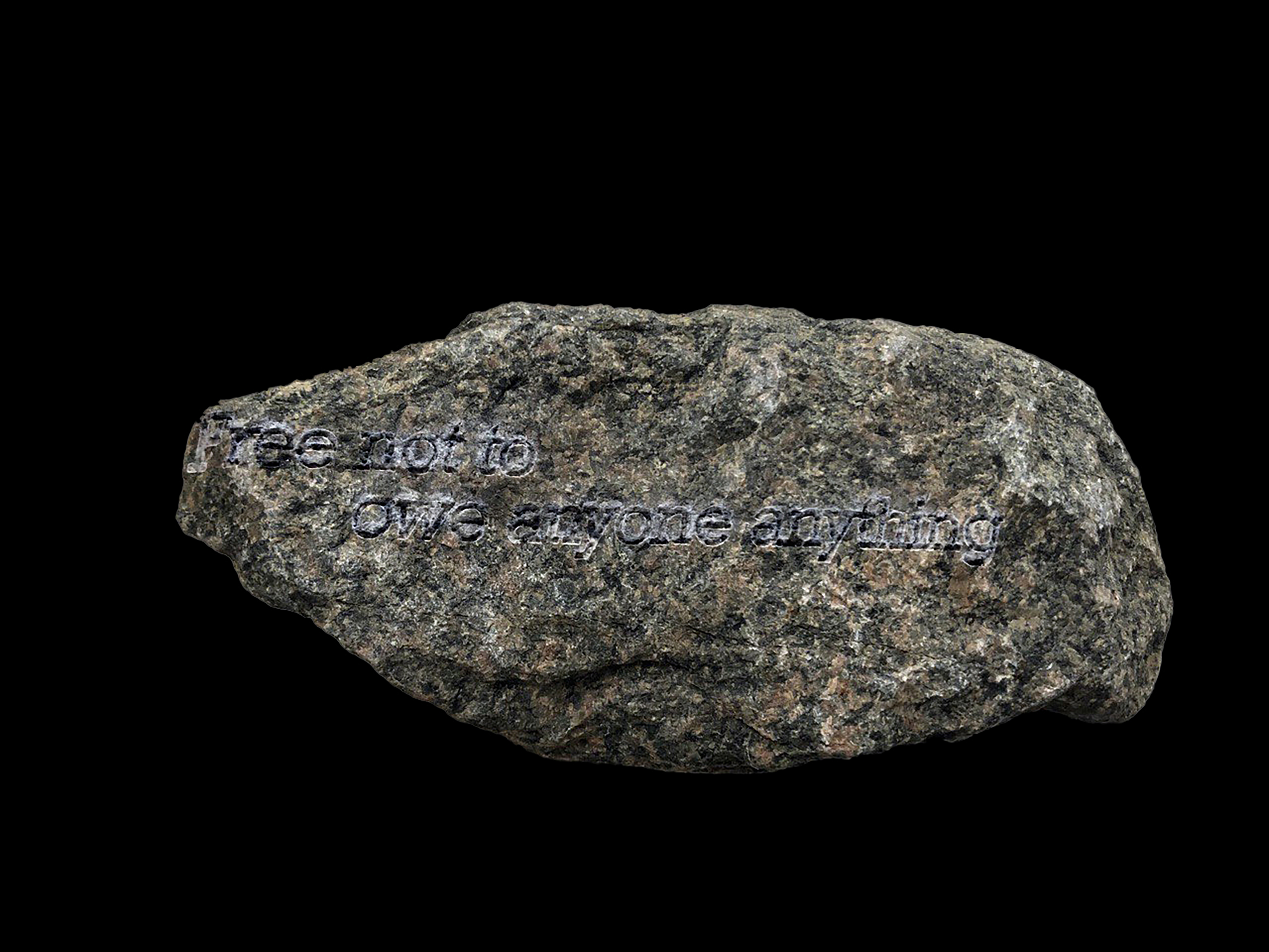

Hannah Hornby, Excavation 0.1, sculpture, 2024

Hannah Hornby: I am working predominantly with sculpture, sound and writing to explore the relationship between man, nature and technology. My practice is driven by fiction and mythology, thinking about our histories, our reality, our future and the moments hidden by time. I am intrigued by repetitive systems, cycles of human behaviours, machine systems and themes of growth and decay. These repetitions are reflected both in the structure of my writing, the movement of the sculptures and the material process of casting. There is a sense of things continuously churning away and ultimately breaking down.

Most recently I have been thinking about how something can be constructed over something else. Concrete poured on top of soil, a vine or moss traversing a brick wall, a moment of time taking precedence over another, a city built on a city, waste dropped on waste. Matter and moments are piling up and then condensing down into layers. I am writing about these behaviours, how we interact on the top layer of land and what land we might inhabit in the future. From these writings I am using plaster, concrete, clay, pencil drawings and projections to investigate textures and spoils in the terrain. The imperfections of a cracked factory floor, a tree root ripping out from below the tarmac, a drain filled with stagnant water. Cycle of growth and decay.

Speculative fiction I believe has been a tool and material for both of us to comment on and probe at current times. You say you want the work to be fictional and yet tangible. For me to balance the fictional and tangible I often root the text in contextual references. For example, during my Water Memories project in Venice, where I explored Venice's relationship to the water, I realised I kept coming across scientific research and theories which were disproven. It was from collecting these stories that my own writing began to play with posing fiction as truth and blurring the lines between realities. How do you navigate this fine line?

I definitely use references to create a space of understanding. Within my work, words, and therefore dialectics, provide a setting and context for allegorical reflection on our daily experiences. I use historical and mundane references to navigate fictional voids that, in some ways, are not so far from the strange everyday life we experience. Coming from a primarily rural background, I am not interested in constructing complex civilisations and cities, but rather in using facts, the otherwise dull, unexpected encounters and experiences as a starting point for the development of a conversation.

I can undoubtedly read a connecting line between your interest in constructed, layered materialities and mine for built-up narratives. There is something in trying to understand history and read between its lines that allows us to reach a better understanding of ourselves. Ursula K. Le Guin said that stories are weapons, allowing us to forge the way we perceive and see reality, the way to perceive existence, and to give meaning to what we actually do. However, I sometimes wonder: is there always a history behind everything?

As artists, writers, or whatever label we want to be called with, my research aims to develop common ground for everyone to question what they are reading, looking at or experiencing. I often write in a stream of consciousness alternating with lucid reflections. The latter usually refer to philosophical, anthropological and historical notions, bringing the reader back to clear profane introspections. I want to push a possible audience to doubt their beliefs, homogenised knowledge and behaviours.

Whether written or physical, within your work, there is a constant repetitive narrative. Materialities are stuck together in a way that is between the industrial and the way limestone forms in a sink pipe; words are cyclical and repeat, and time almost becomes the primary focus. What importance does time assume, and so history and future? And, in what way do you use time within your research and experimentation to explore current concerns? Would you describe your research as an exploration of the natural growth and decay, artificial, cognitive one? Or is it part of a bigger journey?

Simone Marconi, Too-Loose (Garza Che Perde), 2024, sand, water, terracotta, hose pipe, peristaltic pump, contact microphones, speakers

I have always been drawn to repetitions, things in series, patterns. Whether it be the sculptural work of Richard Nonas or research into our histories which shows pre war and post war time as a constant swinging pendulum, or the persecution of witches as an early example of the fear of otherness; which in a new context, is just as present today.

Time is constant and fluid. It moves and sways to and fro like water. It’s heavy and it bubbles up, but too it can lie still and stagnant. I'm interested in picking out fragments of our history, or fragments of the patterns of time, as a way to map out time which is yet to come. To imagine and exaggerate the continuation of the movement or maybe you could say story. By doing so you are able to see the presence in a new light. Pieces of the past and pieces of imagined future come together for the viewer to fill in the gaps. What is important is to move away from the stricter, more linear ways to view chronological time, although at the moment I do use a fairly chronological order with gaps taken out to keep some sort of structure to the work. This could change in the future. But to view time in a more playful and flexible way is to acknowledge the constant growth and decay present in the world. Both good and bad, both that occur organically and synthetically. To be more aware of the shifting changing world, how we are using technology as a tool for development, how we continue to navigate our natural world.

You talk about the mistakes and presumptions about language and its presence within history. How do you achieve, in both language and image, a slipperiness and transformative quality? Are these qualities mirrored in the processes of making and writing?

Simone Marconi, Hiding From A Self I Am No Longer, 2025, wood, audio, elastic bands, bungee cords, jute, headphones, video projection, sleeping bag, cement, notebook pages

I like to call both writing and image codes - codes we use to communicate, develop and order our thoughts.

My work repeatedly uses devices of delusion. These contraptions, sometimes tied to magic and neo-realism, albeit with different aims and methods, are used to address my obsessions, cognitive journeys and reflections. These two movements have undoubtedly influenced both my way of thinking and working in different ways. In my work, there is a constant fall – a free fall, often unpredictable. A natural detachment, which is actually the part that interests me most, linking emotions to the concrete, the perception of the future to the present. A disruptive landing that often manifests as an apparition, somewhere between the psychedelic and the mystical. Displaced "objects" that find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, as if catapulted from a black hole straight into reality. I like to call them "wrong objects" which, coming from a space-time not too far from ours, land and burst into inaccurate sites. Probably, by adding this element, which characterises the narrative intrinsic to my work as well as history in all its religious and political manifestations, allows me to achieve what you call slipperiness. Furthermore, blending references linked to today's social conditions, current events, and the ordinary makes it easier for the viewer to engage with contemporary responsibility and empathy. After all, what is reality if not a slippery fall?

A book that has undoubtedly influenced my interest in this slippery slope to reality is Unknown Language by Huw Lemmey, who delicately engages with the writings of Hildegard of Bingen, becoming a vessel for her eclectic cosmic voice. Lemmey writes about eroticism as a divinatory and revolutionary issue that draws us in, while also exploring illness as a divine manifestation that violently throws us to the ground, bringing us back to reality. This profound journey encourages us to examine our perceptions and the nature of reality itself, fostering a thoughtful exploration of what we believe to be true through "hallucinatory" emotive trips and deceptive transitions.

There is a question that has been bothering me for quite some time now, and I believe it is perhaps more philosophical than related to artistic practice. Your curatorial and artistic work investigates the liminal space that possibly divides the past and the present, materialities in antithesis, constructed stories, playing with the paradoxes that are right before our eyes, but which we often prefer to ignore. I'd like to know your point of view on this: Is there truly a precedent for everything? Within your work, how do you navigate the time-space dimension when the past is uncertain? Is it there that writing steps into the work?

Where I think there is real potential is in this uncertainty. History is biased, a truth from one perspective and time is so huge, a complex slippy web with much which proceeds it, most of it I will never interact with. As I experiment with research and materials some things stick out and some things resurface again and again. Drawing lines between these fragments of uncertain time is a process or an attempt to conjure stories which map out interactions we have with the environment. Rock Strata, for example, is my most recent writing where I consider how we build cities on top of cities, construct over the man made and the organic. The text then moves into a future where we no longer inhabit the world, our lives are enacted within a sort of uploaded space, as an attempt to allow nature to retake the land we so clumsily impacted. Maybe writing and making is an attempt to interrogate parts of our history or presence which seem to glimmer amongst all the information we are bombarded with and playing with ideas of the future is a process of interrogation with something I do not really understand but wish to somehow make sense of.

Hannah Hornby, untitled, 2025

Something which has come up recently in the lectures at RCA was shared meaning. Each of us will have an individual perspective on time, a different reaction to an event or interpretation to a piece of art work. But something is shared in that moment of encounter together. From that shared experience a meaning starts to emerge from the dialogues which may follow, a meaning which isn’t necessarily the same but shared together like interwoven threads.

We both explore man made and the natural. We are both drawn to objects in discard, debris and waste? What is it about these objects that you think we find so intriguing?

We live in a destructive, deconstructed reality - an era where even memory and recollection can be described as debris. An era in which we ingest not only an unnecessarily large amount of information but also microplastics continuously, thereby altering our genetics and the balance of the world, with few alternatives. Islands of waste, mountains of discarded clothes, we are surrounded by what Timothy Morton calls Hyperobjects. Perhaps we may be drawn to them because we are debris ourselves. Everything is debris of something older and bigger; we ourselves are “recycled” material. The temporal dimension is essential here. We are aware that matter has a well-defined history that we cannot fully comprehend. Waste matter, whether natural or artificial, offers us a larger context in which to assemble stories that differ from their original purpose and doom. Breathing life into the finite also adds another layer to the work: it brings us back to a dimension of care and concern, allowing us to take a clear, political stance on the rampant consumerism that involves us all. The problem arises when we question the third, fourth, and fifth infinitesimal lives of these objects. In a West that has been homogenised and sanitised to such an extent that entire portions of space have been sterilised, we find ourselves among the most fragile and endangered species as well as the most detrimental. We live in an ecosystem that we have disrupted and ravaged, but which could well survive without our presence. Our relics and memorabilia send clear messages. These objects - whether new or worn - have been discarded.

Simone Marconi, Free Not to Owe Anyone Anything, 2024, laser engraved rocks

Your work often refers to the imprint left by the interaction between life (often unsettling) and the "unconscious" environment, broadly speaking. There is usually a link to self-destructive behaviour, or at least to the instinct, shared by both humans and the natural world (not that we weren't part of it), to mutate and detach. Let's say that, like the concept, not of collective but community, arising more out of necessity than otherwise, your work is often fractured, and all the distant materialities can be clearly distinguished. The latter made me think, if there is one thing that Thomas More's Utopia teaches us more than anything else, it is that the utopia of some is the dystopia of others. In a certain way, our utopia is the dystopia of our surroundings. We have created botanical gardens as disposable paradises for the ruling classes, eradicated weeds to grow crops we believe are more aesthetically beautiful or useful to our species, and, in some cases, we have wiped out all species that could harm us. According to Proust, the best paradises are those we have lost but, I would add, those we have never experienced? Those that are impossible? Those that do not become reality until we experience them? And then what about dreams?

I try to avoid the terms utopia and dystopia for that very reason you describe. It is subjective and binary, the gap between is far more significant as a space for nuance and complexity. What is increasingly important in my practice is thinking about our relationship to nature, a rather parasitic one at times. To recognise the decay and fractured muddling of us and it, when in reality there is not a separation between humans and nature, just as you acknowledge. But I also don’t wish the work to be too pessimistic or form didactic statements about what we have done wrong. Instead I want to eke out the patterns and movements of the interconnected relationship, the strange textures which mesh together or the ripple effect of an action; pieces of time which might end up in time which is imagined as a means to think alternatively.

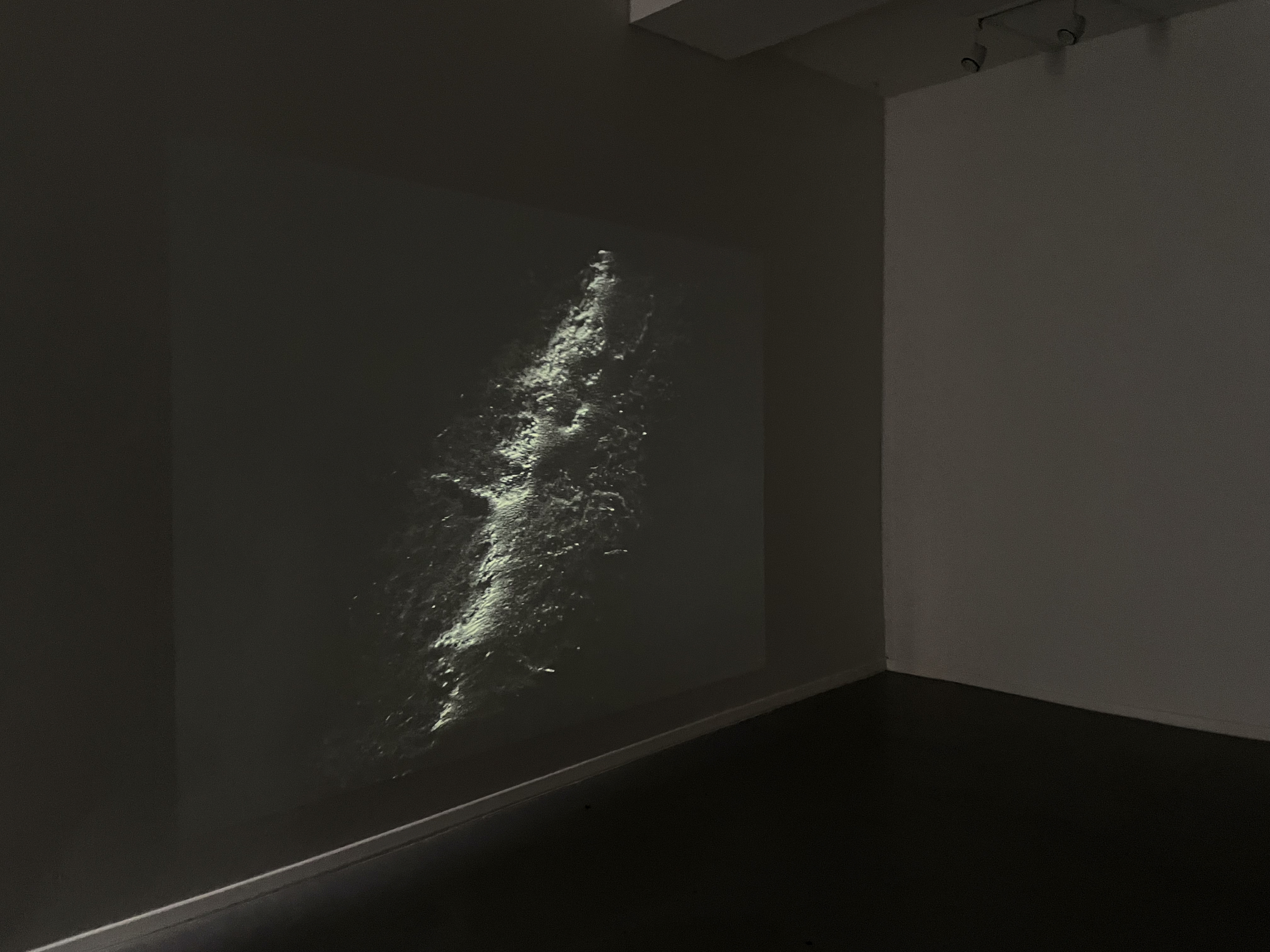

Hannah Hornby, Factory Floor, projection, 2025

Recently I have started reading Lola Olumfemi's book, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise. Lola talks about dreams not in terms of the enlightenment idea, that dreaming is an individual experience, but instead as a collective act in imagining otherwise and building resistance. I also think of Octavia E. Butler’s Blood Child, a story where humans have left earth and arrive in a new land, it questions what we might have to exchange in turn for shelter, where symbiotic ways of life unfold into something closer to parasitic. Recently, I have been thinking about what we return to after a dream or after a collective speculation. Ursula K Leguin however thinks of science fiction not as predictive but as description. The act of a novelist is yes to seek the truth but through devious ways which include invention, metaphors and lies. Suzanne Treister thinks of science fiction as a touch which highlights what is already there but possibly not focused on. So maybe it’s not about leave and arriving but about adjusting perspective and questioning.

I would like to end or possibly pause this conversation by sharing to the audience that since starting this exchange to the present moment we have both enrolled on Masters course Simone is studying Visual Art and Expanded Cinema at Università Iuav di Venezia and is part of the artist-run studio Zolfo Rosso, whilst I have enrolled on the Curating Contemporary Art at the Royal College of Art.

Simone Marconi, Docile Sodom (Where-Does-it-End?), 2026, video, 11'35"

-

︎@hannahhornbyart

︎@simone.marconi_

-

If you like this why not read our interview with Marine One.

-

© YAC | Young Artists in Conversation ALL RIGHTS RESERVED